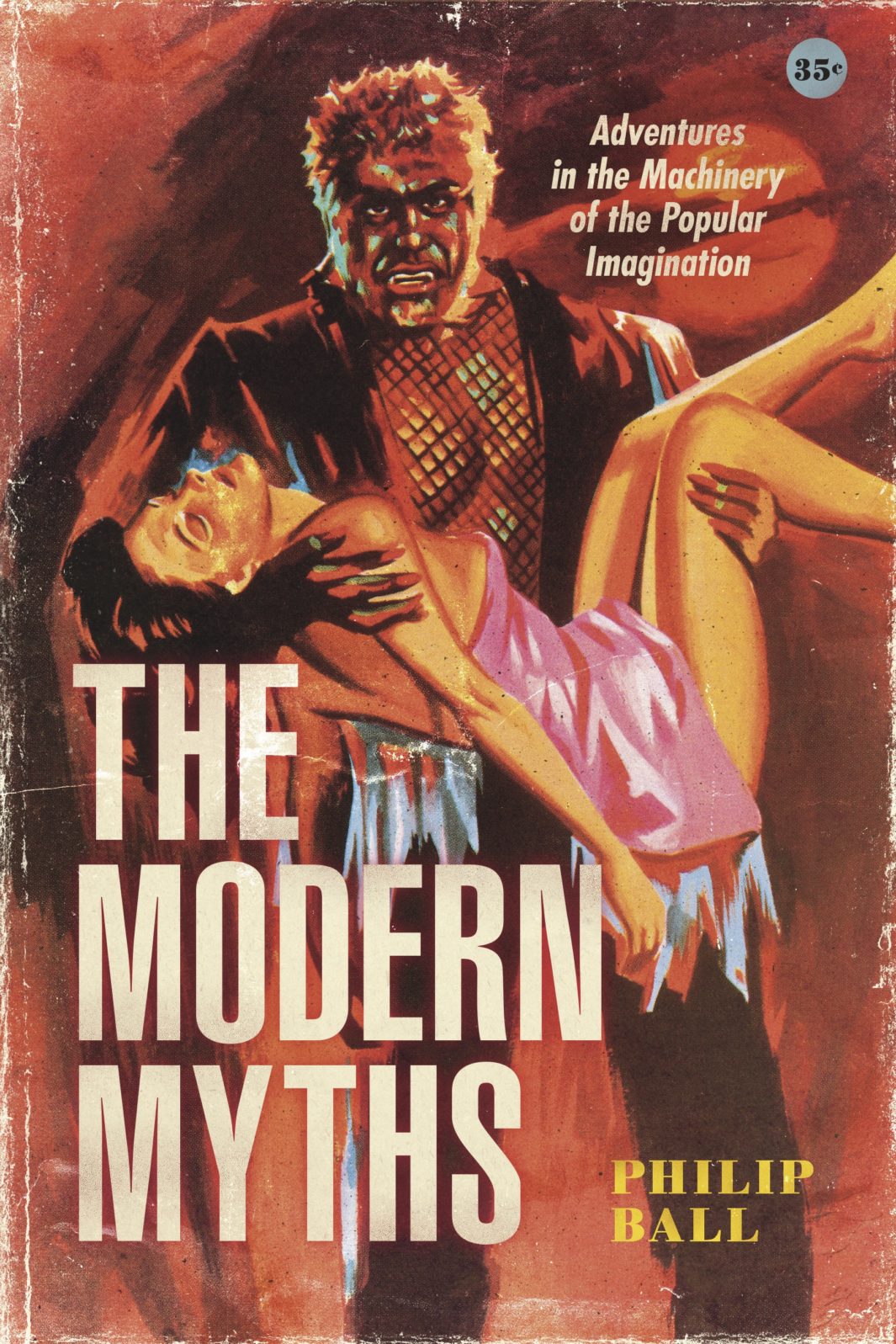

That’s the question science writer Philip Ball, author of The Modern Myths: Adventures in the machinery of the popular imagination (2021), posed recently at The New Yorker. If a dolphin could talk, could we really understand its very different life experiences?

Ball reports that some researchers are trying to translate dolphin communications (“dolphish”) into English:

Today, animal-translation technologies are being developed that use the same “machine learning” approach that is applied to human languages in services such as Google Translate. These systems use neural networks to analyze vast numbers of example sentences, inferring from them general principles of grammar and usage, and then apply those patterns in order to translate sentences the system has never seen. Denise Herzing, the founder and research director of the nonprofit Wild Dolphin Project, which studies dolphins in the Atlantic, is now using similar algorithms, coupled with underwater keyboards and computers, to try to decode dolphin communications. “It may be that our mobile technology will be the same technology that helps us communicate with another species,” Herzing said, in a 2013 ted talk. An even more ambitious initiative, called the Interspecies Internet—founded by the musician Peter Gabriel; the M.I.T. professor Neil Gershenfeld; the “father of the Internet,” Vint Cerf; and the cognitive psychologist and marine-mammal scientist Diana Reiss—seeks to use new technologies to connect intelligent species such as dolphins, elephants, and great apes to one another and to us. “Computer technology is finally allowing us to see inside the world of animals in ways that are showing us that they are complex sentient beings that deserve our understanding and respect,” Con Slobodchikoff, an animal behaviorist who is a professor emeritus at Northern Arizona University, said.

Philip Ball, “The Challenges of Animal Translation” at New Yorker (April 27, 2021)

The history of such efforts to understand and bond, including living with dolphins, goes back to the 1960s.

The skeptics are not mere naysayers. One problem is that, to a great extent, we may simply mis- or over-interpret what dolphins are saying. For one thing, they not only are not like humans but they are not domestic animals like dogs that have lived with humans for many thousands of years. They are shaped by an utterly different world.

Today, many dolphins might as well live on a different planet—a gravity-free world that’s typically blue-green in all directions, with no shadows or smells and a vast and alien sound scape.

Philip Ball, “The Challenges of Animal Translation” at New Yorker (April 27, 2021)

Thus, we don’t hear of compelling data from these efforts:

But Magnasco doesn’t think that anyone has achieved a basic understanding of dolphish. “I’m not yet confident that I know what is the signal, what is the variation, what is the intention,” he said. “You need an extremely large body of data to do that, and it’s unclear that we have enough yet.” Still, there are hints that it might be possible. In 2013, Herzing and her team at the Wild Dolphin Project used a machine-learning algorithm called Cetacean Hearing and Telemetry (chat), designed to identify meaningful signals in dolphin whistles. The algorithm picked out a sound within a dolphin pod that the researchers had earlier trained the dolphins to associate with sargassum seaweed—a clumpy, floaty plant that dolphins sometimes play with. The dolphins may have assimilated the new “word,” and begun using it in the wild.

Philip Ball, “The Challenges of Animal Translation” at New Yorker (April 27, 2021)

Maybe, but such an instance of dolphins recognizing and using a human signal is a far cry from the iconic dolphin goodbye: “So long and thanks for all the fish!” That farewell was made famous as the title of the fourth book in Douglas Adams’s series, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — in which the intelligent dolphins depart a doomed Earth, leaving oblivious humans to their fate.

At least dolphins are mammals. It’s even more difficult to achieve understanding of the communications of intelligent animals that are not remotely like mammals:

With cephalopods such as octopuses and squid, the gap widens further. Our common ancestor with them is thought to be a flatworm with only the most rudimentary of nervous systems; octopus brains are essentially a separate evolutionary experiment in developing intelligence. An octopus has around five hundred million neurons in its body—in the same range as a dog—but they are spread around, mostly in the arms, where they form clusters called ganglia, connected to one another. Even the brain in the center of the body is bizarre, because the creature’s esophagus, through which food is ingested, runs right through the middle of it. Some researchers hold that, with this distributed nervous system, cephalopods might host a “community of minds.” It isn’t clear, for instance, whether it’s the brain or the arms that “decide” what the arms do.

Philip Ball, “The Challenges of Animal Translation” at New Yorker (April 27, 2021)

Many consider the octopus to be the “second genesis” of intelligence, on account of its problem-solving skills. But it’s unclear that those skills are expressed in a language. Similarly, insects communicate but their communications are signal systems (like traffic lights or directional signs).

Some researchers hope that AI, devoid of human prejudices, will bridge the gap by analyzing everything, Ball tells us: “‘We’re really asking people to remove their human glasses, as much as possible,’ Selvitelle said. One Earth Species Project collaboration, called Whale-X, aims to collect and analyze all communications among a pod of whales over an entire season.”

The biggest problem is likely overlooked, however: Human language consists largely of abstractions. It is through the abstractions that it conveys meaning. Think of words like love, hate, power, status, money, rights, duties, honor, reputation, wisdom… What do they mean? These words comprise a cloud of meanings humans share (or don’t, depending on the circumstances). It’s not clear that dolphins, whales, or octopuses ever think that way. Or that AI could bridge a gap between ourselves and life forms that cannot entertain such concepts.

Michael Egnor points out that the real reason why only human beings speak is that human language is not a signal system; it is a necessary tool for abstract thinking — and humans are the only animals who think abstractly.

Real dolphins would never have said “So long, and thanks for all the fish!” because “the future” in which the planet is destroyed is an abstraction too. Dolphins grasp present danger and learn lessons. But a rational mind is needed to grasp abstractions like “The aliens will destroy the planet to make room for a bypass.”

That said, we might learn some valuable information from AI monitoring of animal communications, information that may help us with conservation programs.

You may also wish to read:

Dolphinese: The idea that animals think as we do dies hard. But first it can lead us down strange paths.

and

But, in the end, did the chimpanzee really talk? A recent article in the Smithsonian Magazine sheds light on the motivations behind the need to see bonobos as something like an oppressed people, rather than apes in need of protection.

No comments:

Post a Comment