After the book was dismissed by Soviet censorship, independent translators took a great risk spreading Tolkien’s fiction in the Soviet Union.

Amidst the Cold War, Soviet censorship was suspicious of all things Western. Written by a British writer, ‘The Lord of the Rings’ was no exception. To share the classics of high fantasy with readers in the USSR, Soviet translators attempted to translate it illegally, publish the story under a different name, transform it into a play and even rewrite Tolkien’s book as a whole new sci-fi story.

A sci-fi story

In 1966, Soviet translator Zinaida Bobyr attempted a desperate move to adapt Tolkien’s fiction to the standards of the Soviet literary magazine Tekhnika-Molodezhi (Eng. Youth Engineering).

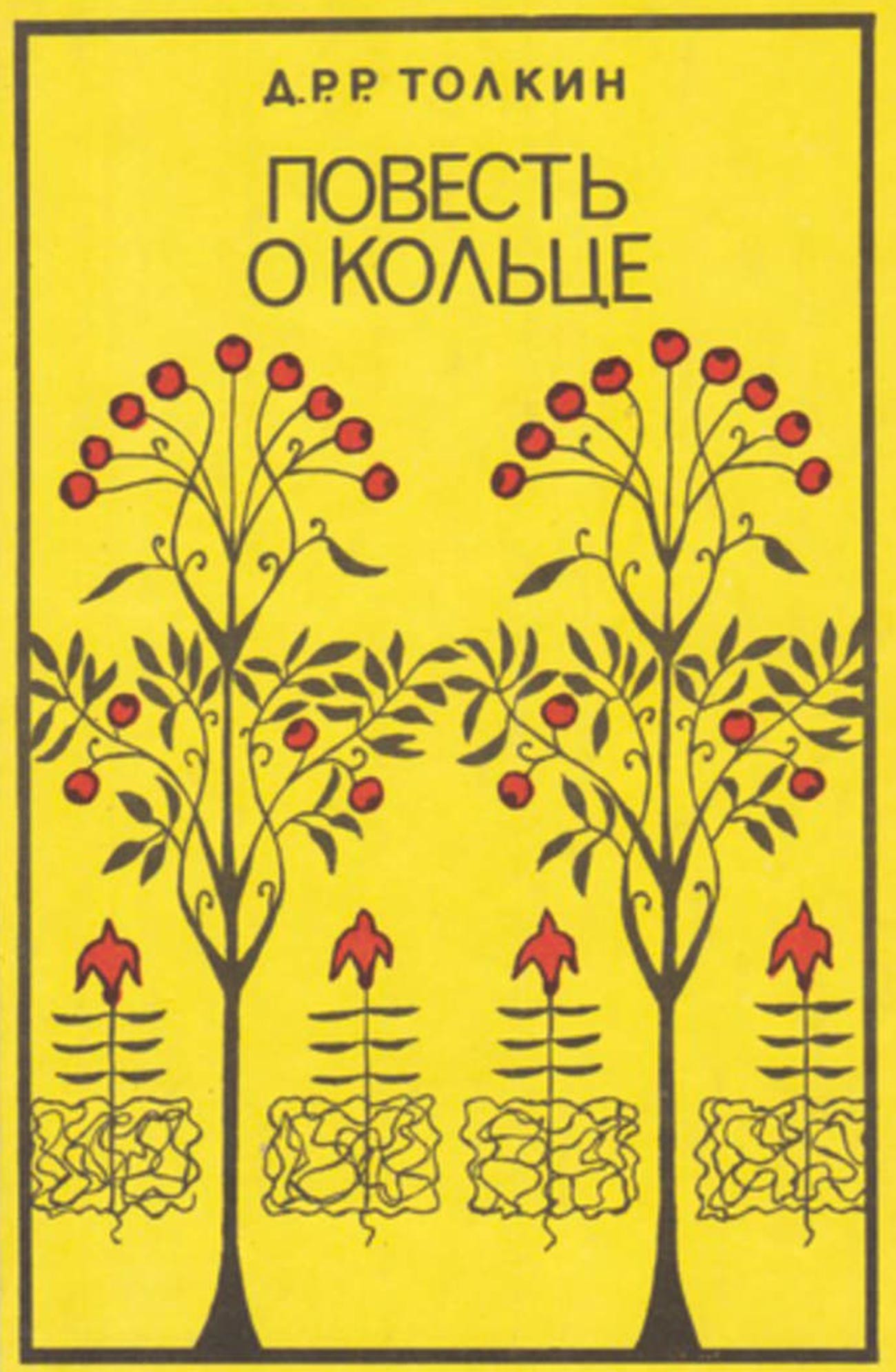

J. R. R. Tolkien, Interprint, 1990

Convinced the Soviet censorship would not allow printing a straightforward translation of the original, Bobyr transformed Tolkien’s epic fantasy into a science fiction novel and hid the magic theme behind the facade of rational scientific discoveries.

Alexandr Korotich (CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Bobyr’s translation, Tolkien’s original tale featured as a story within a different sci-fi story about five scientists who discovered an ancient ring that, they concluded, was a device for storing information which it revealed if stimulated with a spark.

Bobyr’s attempt was unsuccessful, though, as the magazine declined to publish the manuscript.

The First ‘Watchmen’

The first book in the ‘The Lord of the Ring’ series — titled The Fellowship of the Ring — was first printed in the Soviet Union in 1982. Soviet translators Vladimir Muravyov and Andrey Kistyakovsky — who also happened to be fans of J. R. R. Tolkien — convinced a Soviet publishing house to print 100,000 copies of the first volume.

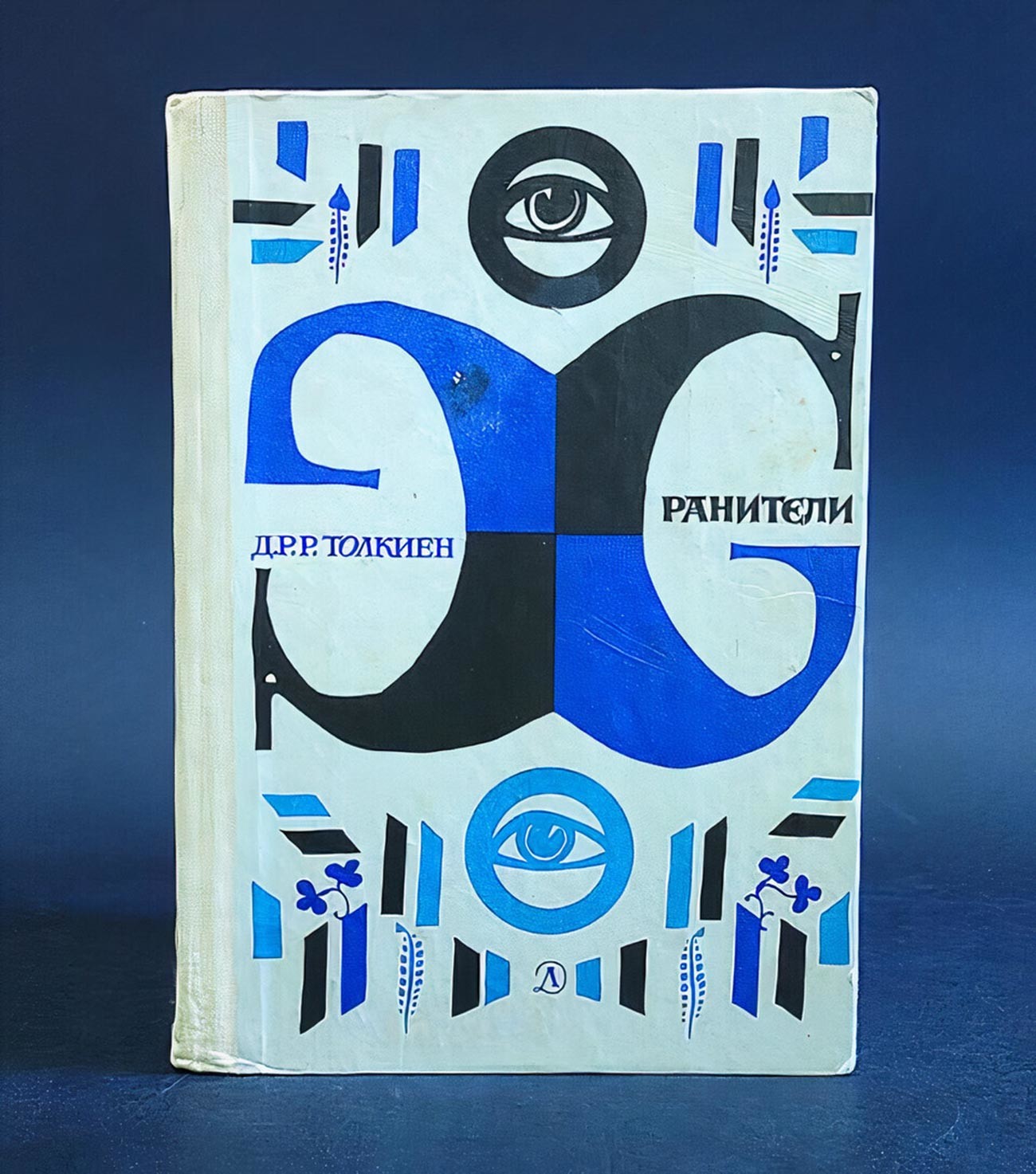

J. R. R. Tolkien/Children's literature, 1982

But the first translation of Tolkien’s writing in the USSR did not strictly adhere to the author’s original. The Russian translation was titled ‘Watchmen’ [Хранители in Russian] and constituted an abridged retelling of the original book albeit without translators’ direct insertions. One of the reasons the translators had to compromise was a suspicious view of Soviet censors, who judged the book to deviate from the canons of social realism, a state-approved art movement in the USSR and other socialist countries at the time.

‘The Evil Empire’

To the disappointment of many in the USSR, the second and third volumes of the adopted ‘The Lord of the Rings’ did not immediately follow despite the astounding success of the first book among Soviet readers.

Zanastardust (CC BY 2.0)

The reason behind the sudden halt was rooted in the geopolitics of the Cold War. On March 8, 1983 — a year after the first publication of Tolkien’s writing in the Soviet Union — U.S. President Ronald Reagan gave a speech where he referred to the USSR as an “evil empire”.

Quickly, parallels were made between Tolkien's fictional world Mordor and Reagan’s reference.

“I didn’t have any anti-Soviet ideas in my head. You see, there are many allusions in Tolkien’s writing. Suffice it to say that his forces of good are located in the West and the forces of evil come from the East,” said Alexandr Gruzberg, another Soviet translator of Tolkien’s work.

Nonetheless, officially sanctioned translation work stopped, giving way to illegal attempts of dissident Soviet translators to introduce Soviet readers to Tolkien’s world.

Illegal translations

Private translators took a risk to translate the two remaining books of the series when it became obvious Muravyov and Kistyakovsky’s translation work would not be continued.

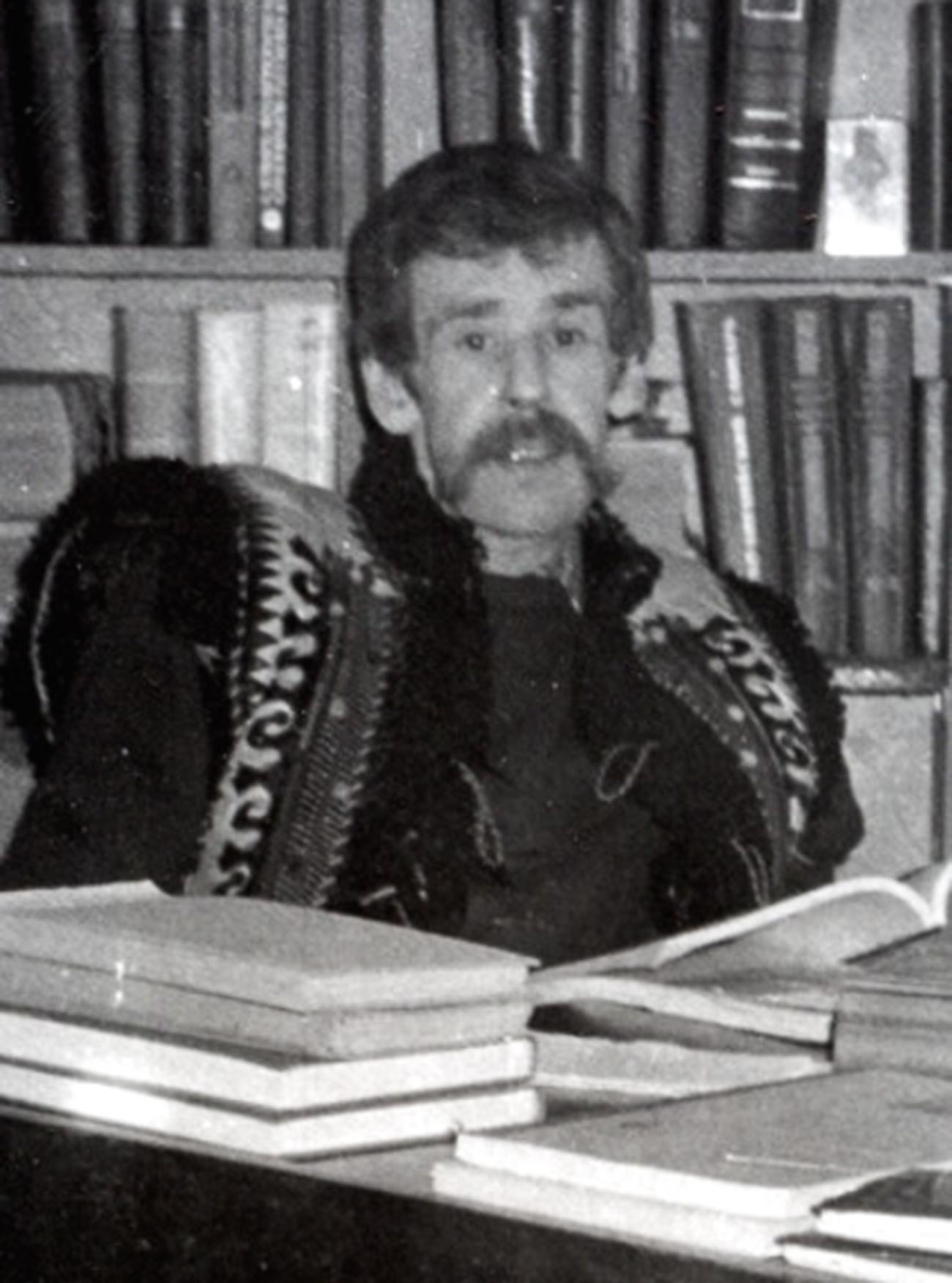

Soviet translator Andrey Kistyakovsky.

Marina Shemakhanskaya's archive“[If caught translating and self-publishing fiction illegally, circumventing the censorship], a person could lose his job or lose the opportunity to continue his education, the possibility of earning money was generally limited and administrative repressions could be applied. And, by the way, it meant ruining the lives of your family, relatives, friends and colleagues,” Soviet philologist Evgenia Smagina was quoted as saying.

Despite the risks involved, private attempts to translate ‘The Lord of the Rings’ to Russian followed the unspoken ban on Tolkien’s work in the USSR. The new self-published versions relied on the achievements of Bobyr, Muravyov, and Andrey Kistyakovsky, the pioneers in the field of translating Tolkien’s complex language to Russian.

Soviet translator Vladimir Muravyov.

Elena Kalashnikova/New Literary Review, 2008Thanks to a wave of unrelated attempts to translate the books, the character of Frodo Baggins still confuses Russian-speaking audience as his name was translated in various ways, each attempting to best transmit the author’s original meaning: Frodo Baggins, Frodo Torbins [a reference to a Russian word Torba — Eng. A feedbag] and even Frodo Sumkins [a reference to a Russian word Sumka — Eng. A bag].

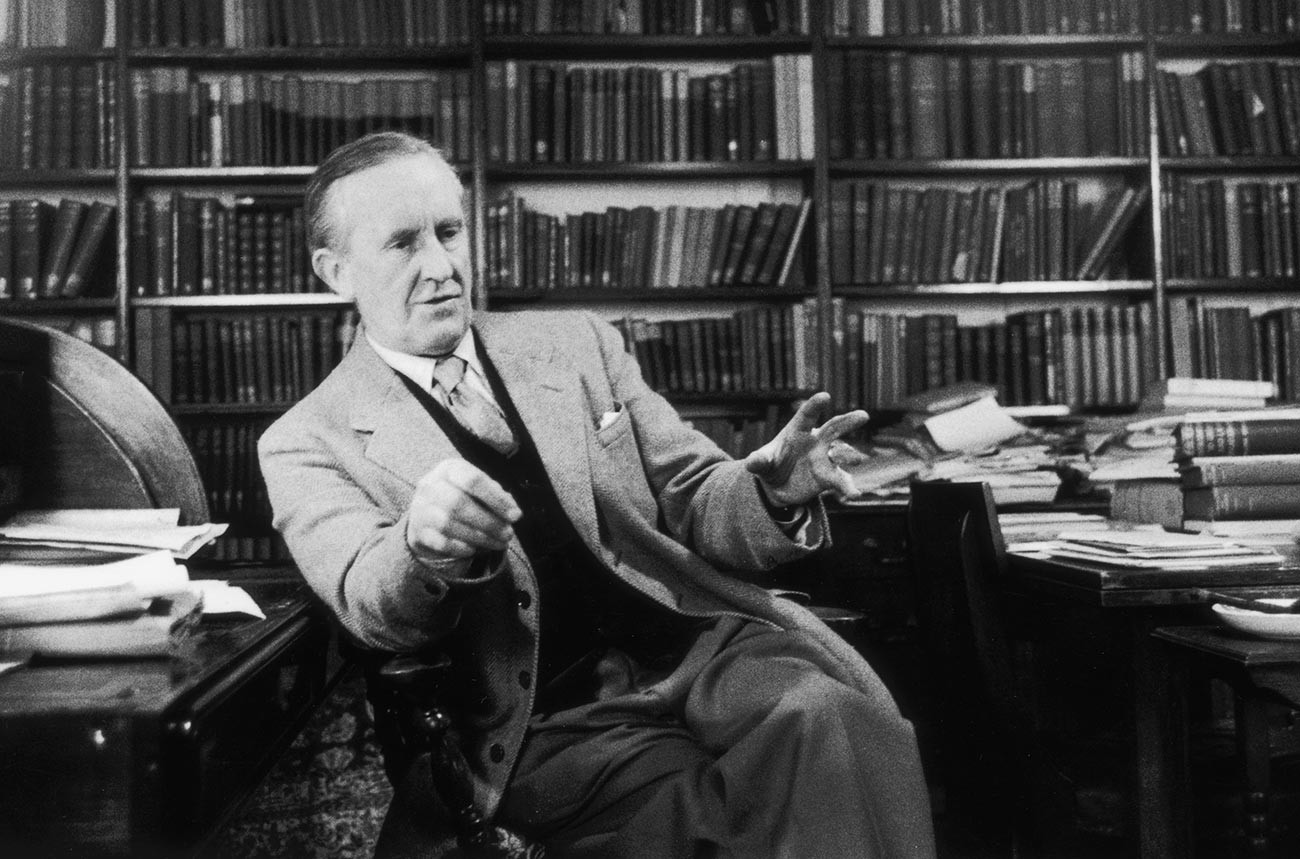

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien ( 1892 - 1973) the South African-born philologist and author of 'The Hobbit' and 'The Lord Of The Rings'

Haywood Magee/Getty ImagesWhen Gorbachev’s politics of glasnost eased the grip of Soviet censorship in the USSR, Vladimir Muravyov resumed his work to translate the two remaining books in the series: The Two Towers and The Return of the King. His colleague Andrey Kistyakovsky did not live to see the moment, as he died in 1987.

In 1991, a group of Tolkien enthusiasts recorded a stage play adapted for TV based on Muravyov and Kistyakovsky’s translation of The Fellowship of the Ring. Most likely, it is the best thing you’ll see on the internet today.

Click here to find out what crazy ideas the Soviets imagined for space colonization (PICS).

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

No comments:

Post a Comment