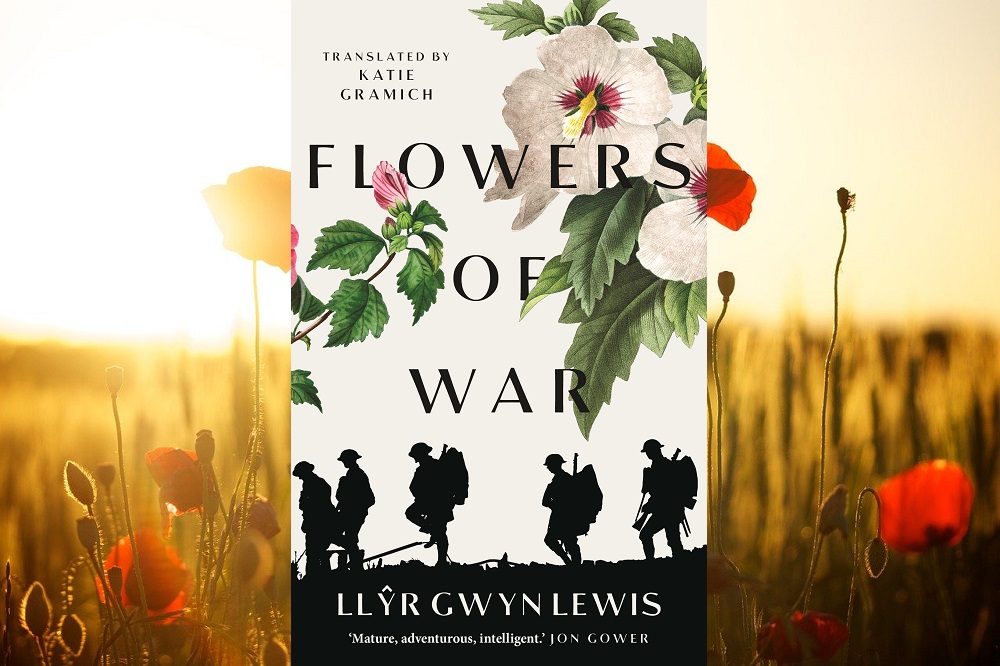

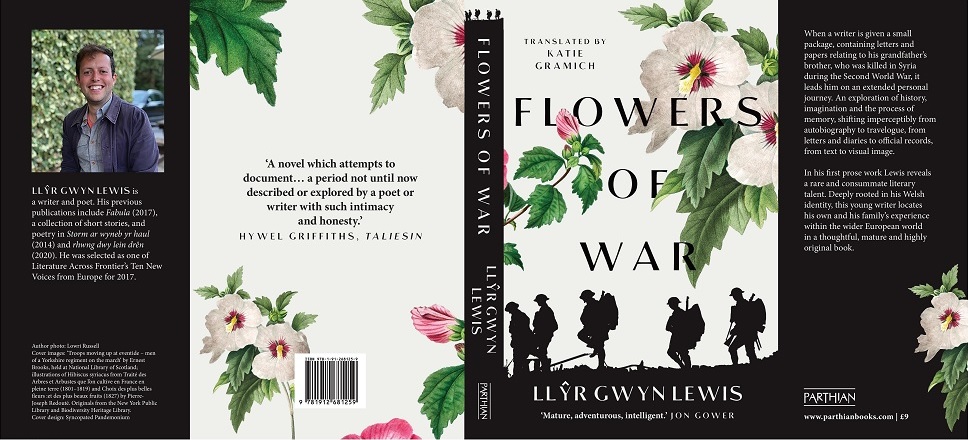

Llŷr Gwyn Lewis’ novel Rhyw Flodau Rhyfel has been translated into English and will be published by Parthian next month. In conversation here with her daughter, the writer Eluned Gramich, Katie Gramich talks about the challenges of translating a work which is deeply rooted in Welsh culture and identity into English.

We’re sitting in the warm living room, my mum and I, drinking tea, a copy of her translation Flowers of War on the coffee table. There are chocolate digestives on a plate, and from the other side of the closed door, we can hear my daughter playing a wooden xylophone to her grandfather. At least, that is how I imagined this interview would take place. Instead, of course, it was through WhatsApp video calls and emails.

My mum speaks calmly and in the full, perfect sentences of an English teacher. I should say, for context, that she was born in Rhydlewis, Ceredigion; that she studied English and Spanish at Aberystwyth and completed her PhD in Comparative Literature in Edmonton, Canada. She’s an Emeritus Professor in English Literature at Cardiff University, having retired a year or so ago. As soon as she retired, she returned to university, not as a lecturer, but as a student of translation at Aberystwyth.

Before then, she had always been defined by her work, tied to her ‘research areas’ and bound by the pressures of academia. Now she’s free to explore what she loves – writing poetry and translating. She was shortlisted for the Poetry Wales poetry prize in 2019 and this year her most recent translation, Flowers of War by Llŷr Gwyn Lewis, which won the Creative Non-Fiction category of the Wales Book of the Year, has been published by Parthian.

After reading both Flowers of War and the original memoir, Rhyw Flodau Rhyfel, I had many questions about the craft and process of translation that I put to her through meandering messages that I’ve attempted to order here:

Eluned Gramich: When and how did you start translating? I know you studied Spanish and Italian at university, and have also learned German … How have these language-learning experiences fed into your translation practice?

Katie Gramich: That’s an interesting question. I think I started translating from Welsh to English and vice versa when I was very young because I had two mamgus (grannies) to whom I was quite close – one an English-speaker with no Welsh and the other a Welsh-speaker with next to no English. I learned a lot from both of them and would often carry stories from one to the other, and obviously I had to translate those stories, though I wasn’t conscious of the process of translating. In a bilingual environment, I think translation is a very natural and barely conscious process, often.

But then, in school, I did Latin and Spanish, and both languages were taught with a heavy emphasis on translating literary texts from the original language into English. I loved it. I still remember the O-Level Latin texts – Caesar’s Civil War and Virgil’s Aeneid – guess which one I preferred? Mind you, Caesar improved my English vocabulary because he was always ‘striking camp’ and shifting his ‘cohorts’ from place to place. As for Spanish, I fell in love with it (helped by a fabulous teacher, L. J. Williams) and I still remember the texts we translated, such as Cuentos americanos de nuestros días and the mesmerising Don Segundo Sombra by the Argentinian writer, Ricardo Güiraldes.

Once, at school, we had a student teacher for Spanish; she marked my translation and said that my word for the Spanish ‘mierda’, namely ‘excrement’, was much too formal for the context; she said that it should have been ‘shit’. I remember being mortified that she said such a bad word aloud in class! But I also learned something about translating the right register from that embarrassing episode.

The weekly translation exercises continued when I went to university at Aberystwyth, where I moved on to translating into Spanish, a much more challenging task. I also did Italian in my first year there and we read – and translated – Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio, among other things. I remember being surprised at what a grown-up satire Pinocchio was, so I learned something about the way texts are changed, sometimes bowdlerised in translation.

Eluned Gramich: Can you tell me a bit about the process of translating Llŷr’s book?

Katie Gramich: Translating Rhyw Flodau Rhyfel – Flowers of War, in English – was quite challenging for many reasons. It’s quite a meditative, philosophical book and it has recurring images and preoccupations which I had to be careful to translate as accurately as I could. While it’s a truly international book, about travel and history, it’s also deeply embedded in Welsh culture, so I sometimes had to mediate for the English reader, who might not know a great deal about Methodist hymns, or medieval Welsh poetry. Llŷr’s sentences are deliberately very long and meandering, with complex grammatical structures, so I found myself trying to be as true to that distinctive style as possible without making the English sound too convoluted. It’s also challenging to translate the work of someone you know and admire because you feel an added pressure to try to do justice to the original language and to the person. Llŷr is from Caernarfon in north Wales, so his natural colloquial language is a bit different from my Ceredigion dialect. However, I had translated some of Kate Roberts’ work before, including Feet in Chains, so I’d ‘tuned in’ to a north Walian voice. Come to think of it, translation is a lot to do with ‘tuning in’, lowering the volume of your own natural voice and trying to let the author’s voice be heard through your mediation.

Eluned Gramich: Exactly. That ‘tuning in’ is important yet can be so challenging too, I think. Speaking of Flowers of War, it was an interesting reading experience for me, knowing you had translated it, yet also being aware of the original Welsh text in the background. Perhaps because I’m your daughter, I could hear your voice and Llŷr’s voice simultaneously. I kept wondering whether you sympathised with the narrator’s complex feelings regarding war – that tension between the desire to be part of the battle and ‘glory’, and the certain knowledge that war is a terrible thing?

Katie Gramich: Not really. I think it’s a young man’s book, quite gendered in that way.

Eluned Gramich: Yes, it seems that way to me too. Following on from that, how do you see your role as a translator? Are you creating a literary work through translation, or are you there ‘simply’ as a transformative agent, enabling communication?

Katie Gramich: Well, a bit of both. I think the enabling of communication is very important – I particularly want Welsh people who can’t read Welsh to have access to Llŷr’s work because it’s a cultural inheritance that they shouldn’t miss out on. I also want Anglophone readers everywhere to read it and realise – wow, there’s some fabulous, experimental work going on in Welsh these days! At the same time, the translated book has to stand on its own two feet, as a work of literature – if the reader is constantly aware that he/she is reading a translation, then the effort has failed.

Eluned Gramich: What was the most difficult part of the translation for you? And what was the most moving or striking?

Katie Gramich: It was all flipping difficult! I loved the poignant picture of the grandparents and the papers the tadcu had kept all these years relating to his dead brother. The way in which Llŷr shows how history is written everywhere, layer upon layer, all around us, is often dreamlike and mesmerising. I loved the trip to London and then the National Archives in Kew when he is chasing after the ghost of his great-uncle. There’s a scene in the underground station that is so atmospheric. This is my version of it:

I watched the dust and dirt swirling about before settling down once more, and I listened to the few leaves near the stairs whirling, rustling, and then lying still. The footsteps of the one or two travellers who had got off the train echoed as they made their way to the exit, and there was one other person in a long coat standing at the other end of the platform. That person coughed, and my gaze caught his as both of us looked at the information board from time to time, watching the remaining time tick away, before the next train thundered its way towards us. The rats down on the track started to scrut once more, and it felt as if the station, which had taken a breath and held it in as the train left, was now beginning to breathe again. I myself felt the same, somehow or other, as I tried to trace and track the Second World War through this city, while it persisted in slipping away from me whenever I caught hold of it. The war in all its horror had thundered through the world, and the world had held its breath. Now we who were left behind on the platform were able to start breathing again, and coughing, and listening to the dust settle, but at the same time we knew that the travellers in those carriages were racing further and further away from us, and that they would soon be at the farthest reaches of the city, at the most distant edge, and that we needed to gather every particle of dust before they reached the ground again. When the next train arrived I did not hesitate but got on it at once and found a seat …

Eluned Gramich: Thank you for that glimpse of the work … I love the way Llŷr inflates the mundane details of the here-and-now – the rat, the man coughing – so that they somehow come to symbolise these difficult ideas and feelings about historical trauma and our connection to the past … But, looking to the future, what comes after Flowers of War for you? What or who would you like to see published in Wales, either in Welsh or English?

Katie Gramich: I’ve just finished translating Llŷr’s poetry pamphlet, Rhwng Dwy Lein Dren, which I enjoyed very much. I’ve also just finished translating your book, Woman Who Brings the Rain, into Welsh. Let’s see if you like it! I’m thinking of translating some Latin American authors into Welsh but am a bit daunted by the thought of copyright issues. I did some translations of Neruda and Borges into Welsh for my recent MA in Translation, as well as Welsh versions of the contemporary German poet, Jan Wagner. Perhaps I’ll contact Wagner, since contacting a living author for permission seems less laborious than dealing with prickly and awkward authors’ estates. I think more literary works from languages other than English should be translated into Welsh – it would bring new voices, styles, and inspiration to an already very vibrant literature.

Eluned Gramich:The possibility of reading Neruda or Borges in Welsh is very exciting. I think this idea – and I think you agree – that ‘every Welsh person can speak English so why bother translating’ is misplaced, perhaps even harmful to Welsh writing … Translation can bring new styles and linguistic play – and ideas too. It’s also a question of cultural confidence, maybe. But I have a feeling we can talk about this for much longer than the confines of this interview would allow. Had this been an interview in ordinary times, the tea would have gone cold, and the biscuits eaten and I think that my daughter would have been knocking on the door by now, demanding that you sing Mynd drot drot ar y gaseg wen…

Flowers of War is published by Parthian in July and can be pre-ordered here.

No comments:

Post a Comment