Gen Z has recently reclaimed the word “yapping”, which means endlessly talking about things of little substance. The term has emerged through TikTok and caught on as a meme, with people proudly sharing the need to spew out words.

Even beyond talking, it seems that words are everywhere. At the slightest feeling of boredom, an average person today scrolls through their social media apps or texts someone. Word games, too, are booming.

But compared to this omnipresence, words themselves as a concept are rarely discussed – where they came from, who spoke them, and so on. When this does happen, one authoritative figure looms large in the form of The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the deliverer of definitions and examples.

Only a few years ago, in the pre-smartphone era, looking up the meaning of a word would mean thumbing through a small, fat dictionary that had thousands of words organised alphabetically. Now, one can simply paste a word onto their Google search bar and see the top result.

Blind trust on Google results is a bad idea. But the OED’s definitions are an exception.

Blind trust on Google results is a bad idea. But the OED’s definitions are an exception.

That the definitions Google throws up are also sourced from the OED is proof of its continued dominance. Not so humbly, it describes itself as “the last word on words”, and “an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and usage of 500,000 words and phrases past and present, from across the English-speaking world.”

The Oxford English Dictionary’s history goes back nearly 140 years ago and is of a community-level, global effort spanning decades – all in the service of language.

The beginnings of the ‘New English Dictionary’ were humble

The first part of the Oxford English Dictionary was published on February 1, 1884, but it covered only a section of words, beginning with the letter ‘A’. Many years prior, when the project was announced, it was intended to be a more small-scale affair.

Advertisement

In 1857, a proposal was put before London’s Philological Society, involved in the study of language. “The proposal addressed the deficiency of existing English language dictionaries and called for the compilation of a New English Dictionary”, according to the OED website.

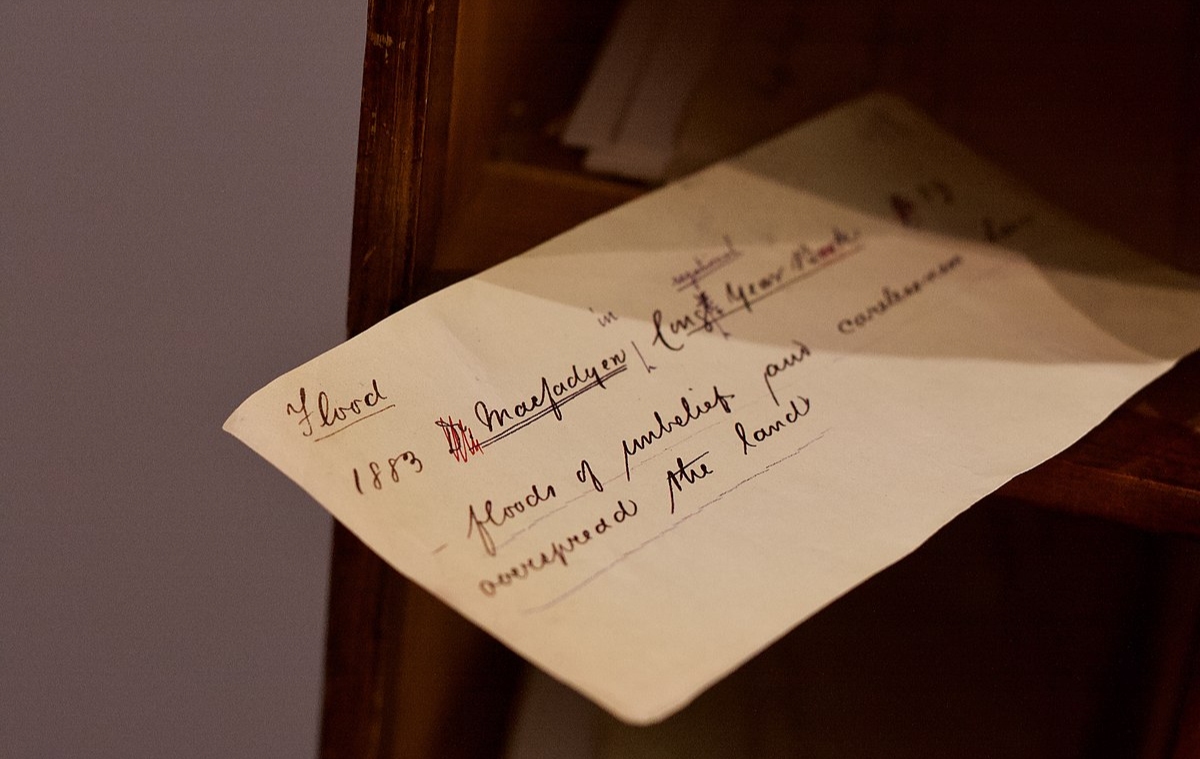

Slip defining the word ‘flood’, as used to compile the first Oxford English Dictionary. (Photo by Daphne Preston-Kendal/CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed/Wikimedia Commons)

Slip defining the word ‘flood’, as used to compile the first Oxford English Dictionary. (Photo by Daphne Preston-Kendal/CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed/Wikimedia Commons)

Archbishop and poet Richard Chenevix Trench, scholar Herbert Coleridge, and philologist Frederick Furnivall got to work. They would choose words “from printed sources dating from all periods of the language’s history”.

Also See | The Express Mini Crossword, made for fans of Indian English

For the task, volunteers examined literary texts to find sources and examples of words and shared their findings for possible inclusions. Each word and information related to it – the meaning and origin – would be written on a tiny piece of paper that they called “slips”.

But over the years, progress on the project slowed.

Advertisement

In comes a lifeline: Oxford University, and an ‘eclectic’ editor

The University of Oxford agreed to publish the compiled works in 1879. This, along with the appointment of a new editor named James Murray the year before, would move things along considerably.

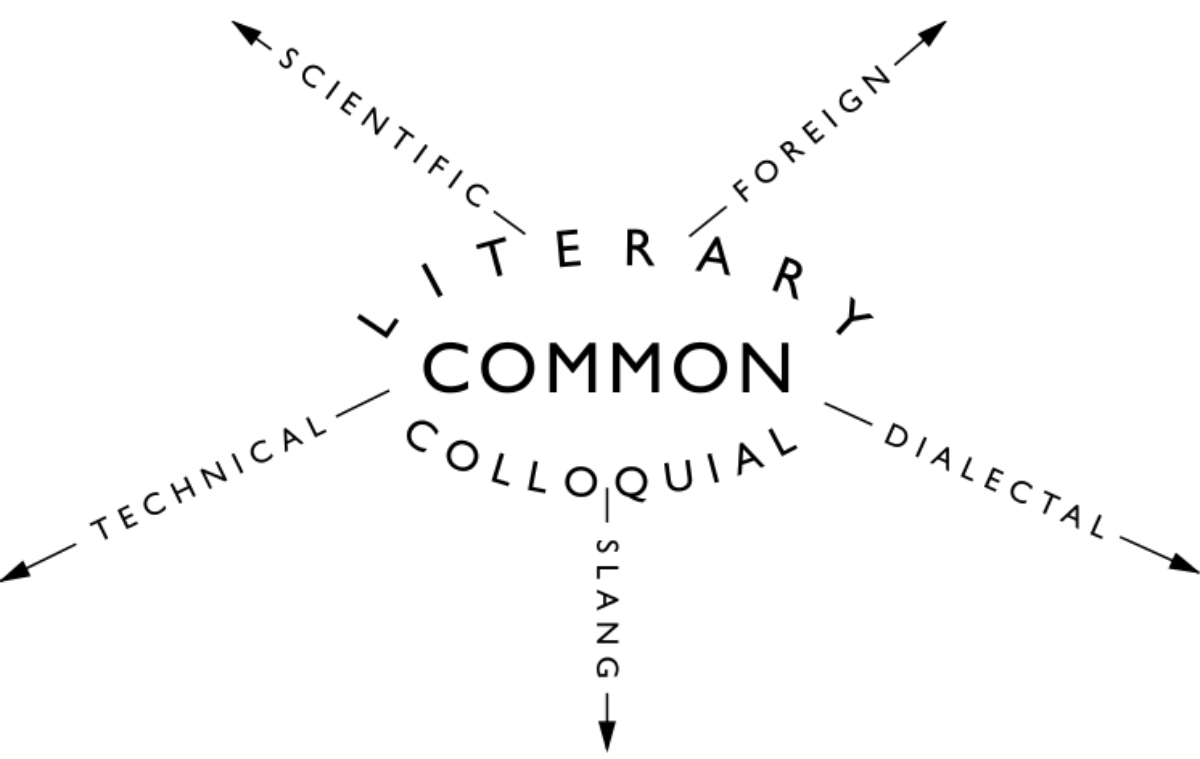

James Murray knew the OED would be ‘incomplete’ without certain kinds of words. This diagram shows his vocab vision for the first edition.

James Murray knew the OED would be ‘incomplete’ without certain kinds of words. This diagram shows his vocab vision for the first edition.

“As editor of the Dictionary, he rejuvenated the volunteer reading program and established a small team of staff… His children (eventually there were eleven) were paid pocket money to sort the dictionary slips into alphabetical order upon arrival,” the website says.

Murray himself had an unusual path to reaching the Philological Society, not being from an elite background. Though he left school at the age of 14, he would go on to study several languages and serve as a school headmaster. He was awarded honorary degrees from nine universities, including Cambridge and Oxford, after his passing in 1915.

To some contemporaries, he seemed a bit eclectic and reclusive, given his deep interest in spending most of his time on activities related to languages and science. At this second wedding, his close friend and one-time student Alexander Graham Bell – the inventor of the telephone – was the best man.

Advertisement

Dedicated as he was, Murray had a shed built near his house for dictionary work.

The call for ‘crowdsourcing’: Americans, women, JRR Tolkien chip in

Anglo-Indian scholar Margaret Murray; and (right) a scene from ‘Lord of the Rings’, written by JRR Tolkien. Both icons volunteered to help finish the OED.

Anglo-Indian scholar Margaret Murray; and (right) a scene from ‘Lord of the Rings’, written by JRR Tolkien. Both icons volunteered to help finish the OED.

Murray expanded the scope of the project, inviting suggestions from volunteers around the world, such as through advertisements and calls to universities. Sarah Ogilvie, a former OED editor and author of the book The Dictionary People: The Unsung Heroes Who Created the Oxford English Dictionary, wrote about one such contributor named Margaret Alice Murray.

Murray was an Anglo-Indian archaeologist, who was living in Kolkata at the time. She was an avid reader of The Times newspaper, which was “distributed throughout the Anglo-Indian community”. The paper also carried Murray’s call for volunteers and was the likely source of her joining the project, to which she’d contribute 5,000 slips.

The volunteers came from all walks of life. Ogilvie wrote, “The story here is one of amateurs collaborating alongside the academic elite during a period when scholarship was being increasingly professionalized; of women contributing to an intellectual enterprise at a time when they were denied access to universities; of hundreds of Americans contributing to a Dictionary that everyone thinks of as quintessentially ‘British’…”

Advertisement

“I was thrilled to discover not one but three murderers, a pornography collector, Karl Marx’s daughter, a President of Yale, the inventor of the tennis-net adjuster, a pair of lesbian writers who wrote under a male pen name…” she added. JRR Tolkien, the author of The Lord of the Rings, was an editorial assistant in the project.

Henry Bradley and co-editors William Craigie and Charles Onions were other notable figures in Murray’s team who would help speed up the work. In 1928, the last part of the dictionary was published.

“Instead of 6,400 pages in four volumes as originally planned, the Dictionary culminated in ten volumes containing over 250,000 main entries and almost 2 million quotations. It was published under the imposing name A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles although it had also come to be known as the Oxford English Dictionary,” the website adds.

In the digital age, the OED has cleverly adapted

L-R: ‘Rizz’ (charm) and ‘Goblin Mode’ (self-indulgence without social worries) were the OED’s ‘Word of the Years’ for 2023 and 2022 respectively. (Photo 2 by 大雄鹰/CC BY 4.0 Deed/Wikimedia Commons)

L-R: ‘Rizz’ (charm) and ‘Goblin Mode’ (self-indulgence without social worries) were the OED’s ‘Word of the Years’ for 2023 and 2022 respectively. (Photo 2 by 大雄鹰/CC BY 4.0 Deed/Wikimedia Commons)

At present, the OED has attempted to keep its relevance in the modern era, in a time when lingo and the English language itself are constantly evolving.

Advertisement

Apart from shifting its information online, the OED keeps updating the lexicon. A BBC report explains that for a word to be added, the current team has to also collect evidence of the word being used, through newspapers, novels and journals.

Oxford also crowns a ‘Word of the Year’, which has also come to symbolise what is happening in the world in a 12-month span. After creating a shortlist, it invites a public vote on the winner. Word of the Year for 2023 was ‘Rizz’, a term popular among younger generations for the ability to attract a partner. Oxford mentioned how the American YouTube and Twitch streamer Kai Cenat helped popularise it, as did TikTok. It reflects an expansion beyond traditional sources, such as newspapers and books, into modern media as sources of new words.

“Our language experts chose rizz as an interesting example of how language can be formed, shaped, and shared within communities, before being picked up more widely in society. It speaks to how younger generations now have spaces, online or otherwise, to own and define the language they use… as Gen Z comes to have more impact on society, differences in perspectives and lifestyle play out in language, too,” it said.

Older generations may grumble, but Gen Z’s spaces (Reels, TikTok, gaming sites) will naturally affect the flow of English.

Older generations may grumble, but Gen Z’s spaces (Reels, TikTok, gaming sites) will naturally affect the flow of English.

However, there is a risk of such words not standing the test of time. Consider words such as ‘Youthquake’ (2017) or ‘Goblin Mode’ (2022). They may become symbolic of larger trends in a year in terms of politics or social changes, but they are not common in terms of usage over a slightly longer period.

Advertisement

Here lies a challenge for the OED: in a time of virality and trends, deciding what deserves to be commemorated is not easy. Especially, at a time when a multitude of opinions are amplifiable, and one book’s opinion is not particularly sacrosanct.

This flexibility, though, might also be its strength. An article in The Conversation argues that the story of the dictionary’s first contributors “reveals that the English language is not owned by a club or a committee or a university or by people from a particular social class or place. It is a global language in its sources, its reach and its ownership. The language, and the literary and scholarly traditions that were built with it, belong to all of us.” And in that, the OED is but one part.

This story is from Express Puzzles & Games, where we publish a delightful Mini Crossword and other brain games. If you like reading or literature, we invite you to give it a try.

No comments:

Post a Comment