Dr. Li Wenliang’s death on February 7, 2020 resulted in an unprecedented spontaneous outpouring of grief on China’s social media. The young ophthalmologist was widely identified as one of eight whistleblowers punished for sounding the alarm about a new SARS-like disease spreading in Wuhan in late December 2019. After receiving an admonishment notice from local police, Li returned to work at Wuhan Central Hospital. He contracted coronavirus, and passed away soon after. Li became a uniquely emotive focal point of public backlash against the heavy-handed opacity cloaking the earliest weeks of the outbreak. He revealed the police notice against him, adorned with his thumbprinted guarantees that he “understood” the nature of his error and would refrain from repeating it. These pledges soon became iconic, as did his statement in an interview with Caixin that “there should be more than one voice in a healthy society.” Though the Supreme People’s Court criticized Wuhan police for their treatment of alleged whistleblowers, Li’s admonishment was not formally revoked until after his death. This injustice elevated the doctor to an almost folkloric status akin to that of tragically wronged figures from Chinese tradition such as Yue Fei or Dou E.

Li’s final Weibo post, from February 1, reads: “Today, the nucleic acid test results came back positive. The dust has settled, there is finally a diagnosis.” Following his death in the early hours of February 7, hundreds of thousands of netizens flocked to this final post to express themselves in the comment section. Censorship organs moved quickly to stop the deluge, demanding that media outlets “control the temperature.” They tried. But the comments did not stop. They became a trend, and then a tradition. More than a year after the young doctor’s death, hundreds of thousands of netizens have persisted in writing on his Weibo, building a living memorial—China’s Wailing Wall.

On the night of Li’s death, the comments were singularly focused on his passing and the toll of the pandemic. The messages changed over time. Netizens began to share their economic anxieties, their outrage over a child rape case, and their hopes for free speech. The Wailing Wall is also a bulwark of memory. As Chinese authorities attempted to recast their early pandemic response as an unqualified success, they flattened the nuances of Li’s apparent political views into a two-dimensional image of a loyal Party member, painting those who remembered his criticism of the system as “hostile forces.” When Li was conspicuously absent from a September ceremony in Beijing honoring pandemic heroes, netizens returned to Li’s page in droves, vowing to remember him.

Selected posts from Li’s replies have been archived at CDT throughout the past year, primarily on our Chinese site. This April, Zhou Baohua and Zhong Yuan, researchers based at Shanghai’s Fudan University, published a broader view of the Wailing Wall’s content, using automated analysis to parse 1,343,192 comments left by 776,449 Weibo users in the 364 days from Li’s death. CDT has translated most of Zhou and Zhong’s contribution to the knowledge of grief, the pandemic, and online speech in China. In addition, we have supplemented the translation with illustrative selections of translated posts from Li’s replies. (Because CDT’s focus is on content that is censored or especially vulnerable to censorship, these selections do not reflect the same balance of sentiments as shown in Zhou and Zhong’s graphs.)

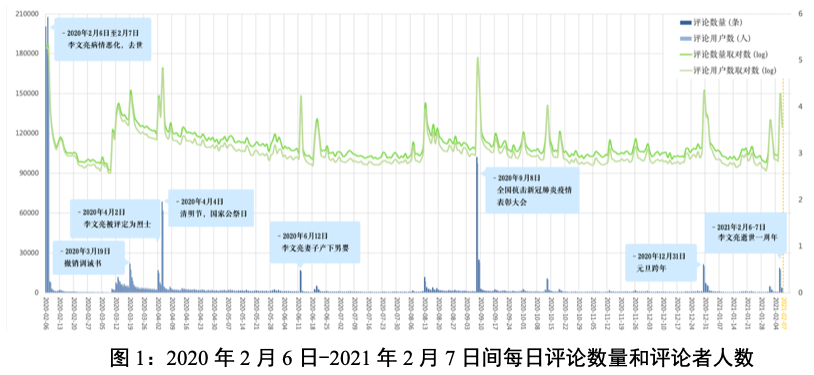

The authors’ primary focus is on the culture of online mourning, which, they write, “has shaped new spaces for interaction and new forms of emotional expression.” Comments are categorized by sentiment—“positive,” “sad,” “angry,” “worried,” and “neutral”—and by topic—mourning, respect, updates, greetings, confidences, and interactions with other users. (This last tendency, the authors suggest, is a relatively novel one in the field of online mourning.) The authors also identify eight “peaks” of activity, defined as spikes including more than 1% of the total all-time activity on the Wall. These coincide with Li’s death and its anniversary; the formal revocation of his admonishment notice; his inclusion among a number of officially recognized martyrs in the battle against COVID-19; the Qingming or Tomb-sweeping festival; the birth of Li’s son; the ceremony at which Xi Jinping handed awards to “Role Models in China’s Fight Against COVID-19,” from which Li was excluded; and New Year’s Eve (December 31).

Users from Beijing, Guangdong, and overseas contributed the highest raw number of posts, while users from overseas, Hubei, and Shanghai had the highest participation rates. Nearly two thirds of contributors were female, and most were established Weibo users, with an average user registration date in 2014. While most were categorized as “passers-by,” with 86% leaving only a single comment, others posted more regularly, with around 10% of total comments left by the most active 2% of users. In contrast with the overall contributor base, these “tomb-keepers” skewed male (57.1%). The authors note that “on average, ‘tomb keepers’ had fewer Weibo followers than ‘passers-by.’ One can infer that their community is one with comparatively weak influence and low participation rates. Accordingly, Li Wenliang’s Weibo comment section became a unique and precious space for them to exchange greetings, share their feelings, and encourage each other.”

Notable Omissions

As the paper was written and published within the PRC, there are inevitably aspects of the Wailing Wall phenomenon that the authors were unable to highlight or openly examine. They do note the existence of a semantic network focused on the terms “owed,” “apology,” “Wuhan,” and “Public Security Bureau” on the night of Li’s death, noting commenters’ “rage and regret that Li had not received an apology before passing away.” The later rescinding of his admonishment notice, and the accompanying identification of scapegoats, appears to have rendered this potentially sensitive topic safe for discussion. Elsewhere, though, there are notable omissions, particularly in terms of the effects of censorship on the wall itself.

One glaring example is the paper’s description of the second highest activity peak. It notes that on September 8, 2020, “Xi Jinping hosted the National Meeting to Commend Role Models in China’s Fight against COVID-19 in Beijing,” prompting a spike of 102,255 comments. It does not explain, however, why this occasion generated more activity than earlier spikes, such as Li’s recognition as a martyr or the birth of his son. In a 70-minute speech, following more than three weeks with no recorded cases of COVID-19, Xi hailed the Party’s leadership as “the most reliable backbone when a storm hits,” and declared that “the pandemic once again proves the superiority of the socialist system with Chinese characteristics.” Xi personally presented medals for distinguished work in the fight against the virus, but despite his public rehabilitation and earlier recognition as a martyr, there was no mention of Dr. Li, let alone a posthumous award. (Dozens of posthumous honors were given, indicated in this list by names in boxes, including to Wuchang Hospital director Liu Zhiming.) Many of those flooding Li’s Weibo at this time simply offered him their own commendations and thanks. Other comments were more pointed:

- @喜妞儿你吃了么: In the past two days, I saw the trending searches were all about you, but they were removed instantly. I cannot describe my anger and sadness.

- @theo楊: Thank you for what you did for us. Your name was entirely absent from the COVID-19 award ceremony. I cannot accept this. I bow to you, the first whistleblower.

- @躲在天台的小孩: This society, this country, has learned nothing in these years except how to forget.

- @多无止境: Brother Li, they haven’t changed at all.

- @巴雷特人: Here is revealed the expectation and desire for justice, as well as the indignation at the system. You are a true hero.

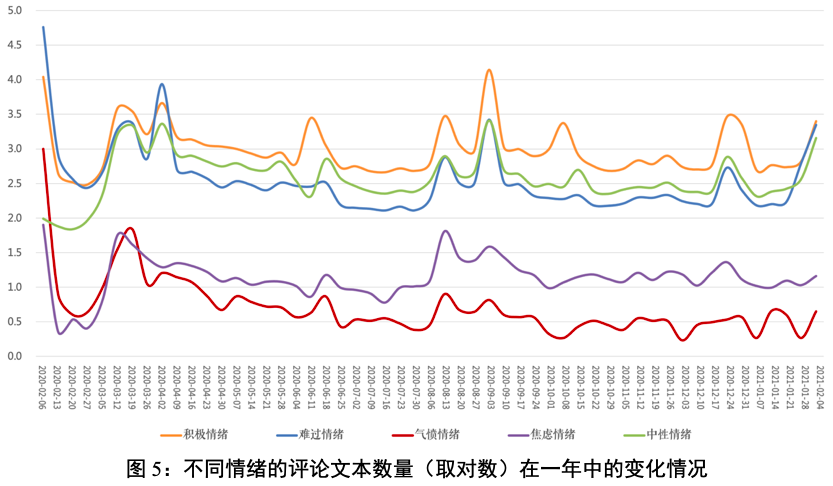

Such anger was not the dominant tone of the spike, according to the Fudan paper’s sentiment analysis graph. Rather, the biggest surges were in “positive,” “sad,” and “neutral” content. It is perhaps curious that an incident sufficiently provocative to trigger a flurry of activity surpassed only by Li’s death should prompt a sharp rise in emotionally neutral posts. As the analysis was conducted on data gathered several months later, it is likely that these results are at least somewhat skewed by deletion of some of the more indignant responses. The University of Hong Kong’s King-wa Fu, who leads the Weiboscope monitoring project at the school’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre, told Ming Pao that the rate of such deletions on Weibo as a whole doubled in the week after Li’s death. Deletion of posts after the fact is only one form of censorship potentially affecting the balance of the Wall’s content: numerous sensitive keywords are blocked from posting in the first place, while some posts are accepted but visible only to their authors.

The paper does not address these possibilities, censorship itself being among the topics most likely to incur censorship. The issue also arises in another small but noticeable spike shown on the graph but not labeled or discussed in the text. On the night of June 19, 2020, Weibo users noticed that the comment section of Li’s final post, while still indicating over a million comments, appeared blank. Most comments later reappeared, but some that had been popular were found to be missing. Initially, only comments posted on June 19 were visible, though earlier ones were later restored. CDT Chinese editors commented at the time, “We hope that the events of the night of June 19 were just a misunderstanding or a false alarm. Even if so, though, they are a reminder that China’s ‘Wailing Wall’ could fall overnight.” CDT Chinese again archived some of the responses:

- @老羅的: I just came to see why ugly souls are afraid of the comments here, and why dirty hands are thinking about getting rid of all their memories

- @Jeane今天看书了吗: I woke up and saw everyone saying that the hot comments were gone. Scrolling to the bottom, they really were no longer there. I was crying silently when I read the comments. I hope you’re well over there, and that your family is healthy and at peace.

- @保守主义本土化研究中心: Dr. Li, surely they wouldn’t clear all of your Weibo comments. We just want to talk, that’s all, just talk.

- @小楼一夜听风雨R: The wall wasn’t demolished, just repainted. Things they didn’t want to see and didn’t want others to see were all buried. So clean, so bright.

- @杨无平: You Sina engineers who delete comments and prevent everyone from seeing the hot comments, do you not feel guilt in your heart?

- @守望者TJF: Is the person doing the deleting really not afraid of going to hell?

- @Toxic-Frog: If this account disappears, there will be no hope left for this country

- @柠檬霸霸duang: Posts have been deleted. Really shows the superiority of the socialist system.

- @李赣比疼: Between humanity and Party spirit, they chose the latter.

- @弹簧御饭团520: If we’re not allowed to be enraged, at least leave us a place to be sad.

The authors write in their conclusion:

Netizens’ collective writing stands outside of the bureaucracy and the media, creating a unique memory of the lives of ordinary people in extraordinary times. [In general,] private, daily practices of “etching [events] into memory,” “refusing to forget,” or “checking in” all indicate a conscious effort to reject amnesia and preserve memory. […] Li’s Weibo comment section has […] given rise to a new written experience of collective memory in the internet era.

“Collective memory” echoes a comment by Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying after the State Council Information Office issued a triumphalist white paper on China’s handling of the pandemic last June: “China issued the white paper not to defend itself, but to keep a record,” Hua said. “The history of the combat against the pandemic should not be tainted by lies and misleading information; it should be recorded with the correct collective memory of all mankind.” This history includes an array of aggressive measures by Chinese authorities to “correct” the collective memory: a sustained barrage of media directives issued throughout the course of the initial outbreak, compiled and translated in CDT’s “Minitrue Diary” series; intense censorship of an interview with another Wuhan doctor, Ai Fen, which prompted its translation into emoji, Klingon, and a Star Wars opening crawl; the detention or other punishments of several citizen journalists and hundreds of social media users for spreading heterodox information; reported interference with World Health Organization investigators; and ever-increasing pressure on foreign media in China, further spurred by retaliatory Trump administration policies. The Fudan authors describe “a conscious effort to reject amnesia,” but are unable to engage with efforts to enforce it. Netizens’ collective writing may be “outside of bureaucracy,” but it is not outside bureaucracy’s reach. Neither, within China, is academic analysis of it.

One useful companion to the Fudan paper is another study, also released in March, by Yingdan Lu, Jennifer Pan, and Yiqing Xu at Stanford University. The three combined machine and human analysis to conduct a broader survey of 5.3 million COVID-focused Weibo posts sent between December 1, 2019 and February 27, 2020, with an explicit focus on measuring the balance of support and criticism for central and local authorities in their responses to the outbreak. Most of the posts were drawn from the larger, post-censorship Weibo-COV database, based at the Beijing Institute of Technology, while a smaller pre-censorship set from the University of Hong Kong’s Weiboscope was used to control for skewed results due to deletion of posts. The authors’ aim was to investigate the interplay of two potentially conflicting tendencies: for the public to assign blame and responsibility in times of crisis, and to “double down on support for existing institutions” in order to maintain a sense of security and predictability. In China, they note, “there are no viable institutions other than the CCP […] The regime is the only source of safety, so even if crises reveal fundamental flaws in the political system, such events may be accompanied by calls to support the existing political regime.”

Criticism largely focused on “perceived lack of action, incompetence, and wrongdoing—in particular, censoring information relevant to public welfare,” while praise was earned by “aggressive action and positive outcomes.” The study found that the two types of posts often spike roughly in unison, reflecting users’ different interpretations of unfolding events and official messaging. Overall, 6.4% of posts about COVID-19 in the Weibo-COV dataset expressed criticism directed at one party or another, while 8.1% expressed support. (Other posts contained, for example, neutral information, or positive or negative commentary not aimed at a particular target.) Similar figures of 5.1% and 6.8% in the Weiboscope dataset suggested that these proportions were not skewed by censors deleting comments after they were posted. The Weibo-COV/Weiboscope comparison does not account for content that went unposted due to keyword blocks or rendered invisible by shadow banning, nor for the restriction of a post’s reach by search blocks, etc. These limitations are acknowledged in the paper’s broader conclusion about censorship volume:

Focusing on what is most likely to be censored—critical commentary—we find an extremely low rate of content removal. Out of 47,912 critical posts made during our study period, only 55 posts (0.11%) were censored, and out of 11,901 critical posts targeting the government, only 27 (0.23%) were removed. While the Chinese government may use other strategies to censor online discourse—e.g., intimidating or co-opting key opinion leaders, preventing content containing certain keywords or phrases from successfully posting to Weibo—our data suggest that large-scale, post-hoc removal of critical commentary did not occur.

The main target of criticism (46%) was the Chinese public, which berated itself for breaking public health guidelines; spreading rumors; discriminating against people from Wuhan and Hubei, among other groups; and for “consuming exotic animals.” Local governments were the next most common target (25%) for their perceived failings in pandemic control. Meanwhile, healthcare workers and organizations received the most support (48%), followed by local (17%) and central governments (16%).

The Stanford paper concludes:

Whenever a crisis occurs in an authoritarian regime, there seems to be an immediate impulse among commenters to find an outpouring of public anger. While capturing negative sentiment is important to our understanding of these countries in times of crisis, the findings of this paper caution against narrowly focusing on negative sentiment.

Even the death of Li Wenliang produced “simultaneous bursts of general criticism and support as well as simultaneous bursts of criticism and support targeting the Chinese government. In other words, events affected online public sentiment, but not in a single direction.” At the same time, however, the paper highlights one respect in which the wave of criticism after Li’s death was exceptional, appearing to briefly upend a generally iron rule of political trust in China.

The authors note that “strikingly, the level of criticism targeting the central government is nearly four times higher on February 7 than it was on January 23 (11% of all critical posts). […] In contrast, the level of support for the central government is less than half of what it was on January 23 and falls below support for local governments (9% of all supportive posts).” This, they point out, is “a pattern of public sentiment unusual in the study of China”:

Between the two largest bursts of discussion in this time period—the January 23 Wuhan lockdown and February 7 death of Dr. Li Wenliang—criticisms of the central government increase dramatically while support for the central government declines precipitously, falling, by February 7, below the level of support directed at local governments. Over the past decades of China research, numerous studies have consistently found that trust in and satisfaction with the central government is high, and always higher than that for local governments (Jiang and Yang, 2016; Lu and Dickson, 2020; Shi, 2001; Tang, 2005, 2016; Truex and Tavana, 2019; Zhou et al., 2020). With the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, we observe a deviation from this pattern. Weibo users are taking the central government to task for censorship and information manipulation, questioning a core feature of the Chinese political system. However, this deviation does not last; the level of support for the government steadily increases after February 7, while the rate of criticism falls.

Other research, including large-scale surveys recently described at The Washington Post by York University’s Cary Wu, have shown that the subsequent course of the pandemic restored and reinforced the status quo in terms of political trust. But its brief reversal highlights the extraordinary resonance of Li’s death, and perhaps helps explain the Wailing Wall’s widely unexpected survival. It may have been preserved as a pressure valve, or a fire alarm.

Zhou Baohua: Professor at Fudan University’s School of Journalism and a researcher at the Center for Information and Communication Studies, Fudan University, as well as the Center for Studies of Media Development, Wuhan University.

Zhong Yuan: Doctoral Researcher at Fudan University’s School of Journalism.

Social Media, Collective Mourning of Public Figures, and Extended Affective Space

Digital and social media are changing the shape of death and mourning, expanding the traditional “space for grieving and remembrance” (Brubaker et al., 2013). Netizens not only can harness the internet to construct a digitized memorial for themselves and their loved ones, but also express collective remembrance through the social media accounts of public figures to whom they are not related. One may say that online mourning for public figures has shaped new spaces for interaction and new forms of emotional expression that are worthy of analysis and study. It is in this vein of inquiry that the comment section of Dr. Li Wenliang’s Weibo account has become an example of online mourning and emotional expression with both universal and particular significance during the novel coronavirus pandemic. This report uses computational communication methods to crawl over 1.34 million comments on Dr. Li’s Weibo page from February 2020 to February 2021 in order to understand this particular online mourning event and inquire into general theoretical problems of digital mourning and the extendability of emotional space.

[…] In this paper, we argue that as time passes a “dialogue” between mourners and Li Wenliang has come to exist. However, unlike traditional conversations with the dead at grave sites or through private letters, dialogue with the dead on social media is by default seen and read by others (i.e. they are social expressions), thus creating the potential for communication among mourners. Beyond reading the comments left by other mourners, netizens also interact and converse, creating a new culture of mourning and remembrance (Walter, 2001). In short, this paper will analyze how netizens continue to communicate with the dead and with each other in “extended affective space,” thus perpetuating this unique venue for emotional communication. […]

Research Discoveries and Analysis

Li Wenliang’s Weibo comment section acts as an online community of mourning. Li’s account brought people together from across the country in collective remembrance. In the year following his passing, over 777,000 Weibo users left more than 1,340,000 comments in an unbroken stream throughout the year. On the average day, 3,014 users left 3,659 comments—the median was 1,255 comments by 890 users per day. Over the course of the year, there were 154 days (42%) when comments exceeded 1,440 (which is an average of at least one comment per minute). Even the day with the fewest comments (March 8, 2020) still saw 382 people leave 443 messages.

The survey showed eight comment peaks (defined as daily comments exceeding 1% of total yearly comments) over the course of the year. The attempted resuscitation of Li Wenliang on the evening of February 6 and his death in the early morning of February 7 marked the highest peak—352,197 people (45.4% of total yearly commenters) left 408,491 comments (30.4% of total comments).

The seven smaller comment “peaks” were [with translated examples added by CDT]:

- March 19, 2020, when Li Wenliang’s admonishment notice was rescinded (22,135 comments, 1.7% of the total)

- @正宗天下之大: Old boy, this is how their investigation turned out.

- @卟哒卟哒的吃火锅: Today, our whole family watched the news until we were so angry we turned the TV off. Dad was so angry he smoked a cigarette—he’d already quit for a while now but today I didn’t say anything. Mom didn’t even finish eating before setting off for the night shift at the hospital. Everybody knows right from wrong in their bones.

- @KiygasuTsushinomi: Again with the cannon fodder, they’ve found a couple of sacrificial lambs. Once they finished wronging the doctor they moved on to wronging the policemen.

- @蓝玛飞蓬: Good morning Dr. Li. I saw a great comment: A grain of the sands of time is a meteor when it lands on the head of the Zhongnan Road Police Station. The world didn’t improve after you said “there should be more than one voice in a healthy society.” Instead, things got worse. Last night CCTV’s Weibo account censored comments on its posts.

- @泥煤肿蠱: What power can force every major media organization to cover, in identical language, an admonishment notice issued by a local police station calling you a rumor monger?!

- @一口一个小馒头5: It feels like the results of this investigation are humiliating us, like they’re saying, “I can do anything because what are you going to do about it?” I will still remember. I’m going to buy a whistle and every February 6 at 9:30 p.m., I’ll blow it.

- April 2, 2020, when Li Wenliang was designated a martyr (17,086 comments, 1.3% of total)

- @既沐清风又饮烈酒: The Weibo of the dead has become the Wailing Wall of the living.

- @鹤舞寒沙: Hello, Dr. Li! They’ve deemed you a martyr a day from Qingming—you’ve been martyred just in time. It feels surreal. In fact, I’d rather you were alive. I wish you weren’t to be hung on a wall and hypocritically commemorated. When you’re unhappy, go curse them out for a bit. And if you’re happy later, then go thank them and eight generations of their ancestors. The sky is still so dark without Liang… [Liang, the third character of Li Wenliang’s name, means light.]

- @那只是曾经198101: Martyr? That feels a bit like black humor!

- @师大桂林蒋: I hope there’s no COVID-19 in heaven, and no “stability maintenance”! And no admonishment notices! Tears are pouring from my eyes! I planned to wish you a safe journey, but… why don’t good people have good karma?

- @NewLifeStory: It didn’t turn out the way it should have, but at least we got some kind of explanation before Qingming… That must be some comfort to your wife and son 🍗 Thank you

- @IlIlMNHL: I’ll always remember the tears I cried and the words I cursed that night you surely didn’t want to be a hero you only wanted to be a ordinary conscientious doctor good night

- @Qingshanlushui1976: The whistleblower has become a martyr. What a tragedy for our society.

- @hk2922: Doctor Li, although many of the comments here have been deleted, I hope that all of our remembrances will not be deleted. We’re always thinking of you.

- @于庸散客司: Being deemed a martyr and an “advanced” person absolutely cannot redeem their wrongful admonishment, nor can it cause me to forgive CCTV and all other TV stations for reporting on the admonishment. Leaving out your doctor label to call you a “citizen,” leading us to believe it was “safe,” now the whole world is paying the bill with its life. This apology will never be able to right the past.

- @海底也是否蔚蓝: You’ve been deemed a martyr but the virus that killed you is still devastating the globe and the powers that humiliated you still sing songs of praise in the imperial court.

- April 4, 2020, the date of Qingming Festival and National Memorial Day (68,594 comments, 5.1% of total)

- @Wong·Ray: Dr. Li, today is a national day of mourning to grieve martyrs like you and the thousands upon thousands of those who paid the ultimate price in the pandemic. To tell the truth, my mood is one of profound grief because this country still only has one voice.

- @Voicejoker: Dr. Li, today is a national day of mourning to remember the martyrs. But I wish there weren’t any martyrs in the world. Those of us who have been protected by heroes wish they could protect the heroes, too.

- @长欢如是: A gentleman’s spirit is as high as a mountain and as long as a river.

- @小熊wul: They say you are a martyr, but I still wish that you were living a peaceful life in this city just like us, ordinary Little Li. Rest easy 🙏🙏🙏

- @Pessimist·: Dr. Li, I still like calling you that. It usually rains on Qingming around here. In a moment, the whole country will be silent for three minutes. We’ll only be quiet for three minutes. But because you didn’t remain silent then, you’re now silent forever. Miss you.

- @针骨棉花团: Mourning without accountability is a sham.

- June 12, 2020, when Li Wenliang’s wife gave birth to their son (17,186 comments, 1.3% of total)

- @YYYYY__1_: Mother and son are safe. Dr. Li, you’re a father now. //@热依扎扎节节高: Your second child was born, mother and child are safe, six catties, 9 taels.

- @凶狮03舒绛: Your last gift to your wife arrived today.

- @颐祥無为自在: Today, when I saw the news about your son, I burst into tears. May the world treat him kindly.

- @曲中人040102: It’s obviously good news. Everyone is congratulating you. Why am I crying reading these blessings…

- @王不留行花流星: Congratulations that can’t be said aloud, tears that flow silently

- @麻醉医生123: I hope that the baby grows up healthily and tells the truth like his father when he grows up

- @许州hjo: Child, I hope that when you grow up, there are no longer such strange things as police admonishing doctors for spreading rumors

- September 8, 2020, when Xi Jinping hosted the National Meeting to Commend Role Models in China’s Fight against COVID-19 in Beijing [from which Li was excluded] (102,255 comments, 7.6% of total) [See examples in introduction]

- December 31, 2020, New Year’s Eve (2,156 comments, 1.6% of total)

- @该用户已提交注销申请: Dr. Li, I made a bowl of Yangchun noodles for you. Eat slowly. There are still thousands of lights in the world, COVID is not yet gone, but it’s okay. People have calmed down a lot. Your whistle is like a glimmer of light in the sky, very small, but it has not faded.

- @蒜香橙花: Dr. Li, this wasn’t a good year, but it’s finally over. I wish you a happy new year.

- @恬恬的大宝剑: A letter of admonition at the beginning of the year, a letter of judgement at the end of the year (Zhang Zhan). The way to solve a problem is to deal with the person who raised the problem. 2020 is full of shame.

- @Alice2590: At dawn on December 31, 2020—today last year—many people were queuing up to buy masks after hearing you blow the whistle. Miss you, and miss your conscience!

- @面壁人Q: Some people rewrite history. I’m here to leave you a message, I will be back every year, I will not forget the truth.

- @一个豆包vvDoukkkkate: Salute to the whistleblower, this world is much warmer because of you.

- @廿壹: I will remember you, I will remember the tears from that night.

- @Made-In-Philosophy: Seeing so many comments below, I suddenly feel I’m not alone.

- February, 6 2021, the one-year anniversary of Li’s death (18,744 comments, 1.4% of total)

Graph 1: Daily comment and user totals between February 6, 2020 and February 7, 2021.

After excluding the comment peaks detailed above, the average number of comments left between February and April 2020 was 2,925 per day, noticeably higher than the 1,468 comments left per day between May 2020 and February 2021. However, the average comments-per-day remained consistently above 1,000 after May—demonstrating that comments did not trend downwards with the passage of time.

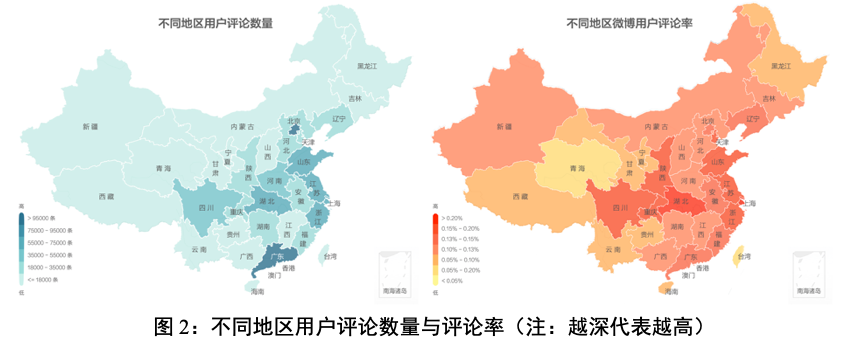

Commenters came from all 34 provinces (including direct-administered municipalities, autonomous regions, and special administrative regions), as well as overseas. Although the fewest number of comments came from Macau Special Administrative Region, over 1,112 users from Macau left 1,770 comments over the course of the year. This was collective public mourning on a national scale. In terms of absolute numbers of comments and commenters, those originating in Beijing, Guangdong, and overseas occupied the top three spots, accounting for 10.2%, 9.5%, and 8.1% of total comments, respectively, followed by Jiangsu, Shandong, Hubei, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Sichuan, and Henan, accounting for a total of 37.8% of comments.

To conduct a deeper comparative analysis of regional differences, we calculated participation rate (number of commenters from a region/total Weibo users from said region) as a proxy for active participation. In this analysis, the top three regions are overseas, Hubei, and Shanghai, with percentages reaching 0.33%, 0.24%, and 0.23% respectively. Shaanxi, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, Tianjin, and Chongqing follow, with user participation rates between 0.15% and .20%. The highest absolute number of comments came from Guangdong and Beijing, but user participation rates did not reach 0.15%—demonstrating that the primary reason for the high numbers was simply a reflection of the large number of Weibo users.

Graph 2: Regional comment totals (left) and participation rates (right); darker colors correlate to higher total/rate

Among the 770,000 commenters, 87.2% were common users (those without the “Big V” [similar to the Twitter “Blue Check”]). Women made up 63.3% of commenters, leaving 61.0% of comments; men made up 36.7% of commenters, leaving 39.0% of comments. According to Sina Weibo’s Data Center, Weibo’s user base is 54.6% female and 45.4% male. From this one can see that female users’ participation rate was higher than that of male users.

“Old” Weibo users also had higher participation rates. Accounts registered in 2010 and 2011 accounted for 12.9% and 15.6% of total participants, respectively. The mean and median account registration date was 2014. Participation dropped as accounts got “younger,” meaning the user registered closer to the present day.

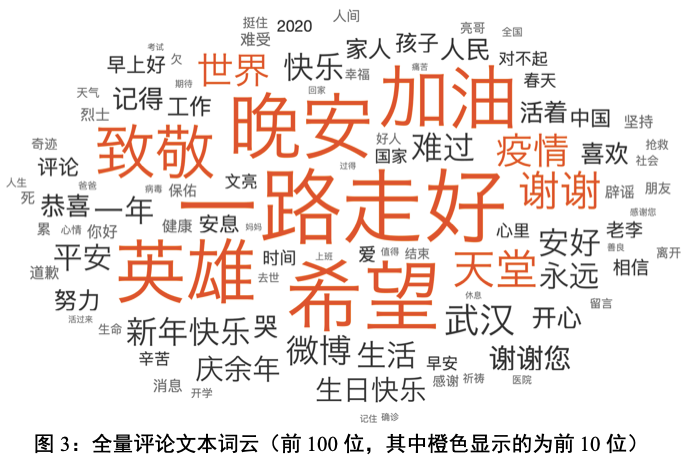

After cleaning up the comments by removing usernames, emojis, and common words like “Doctor Li, Li Wenliang, and Mr. Li,” the 10 most common words were:

- “rest in peace” (91,083 times, 6.3% of the most common 100 words)

- “hope” (81,655)

- “good night” (74,621)

- “hero” (70,246)

- “add oil” (68,718)

- “respect” (53,310)

- “heaven” (31,509)

- “thank you” (30,630)

- “pandemic” (25,057)

- “world” (24,742)

Graph 3: Word cloud formed of the 100 most common words, with the 10 most common in red.

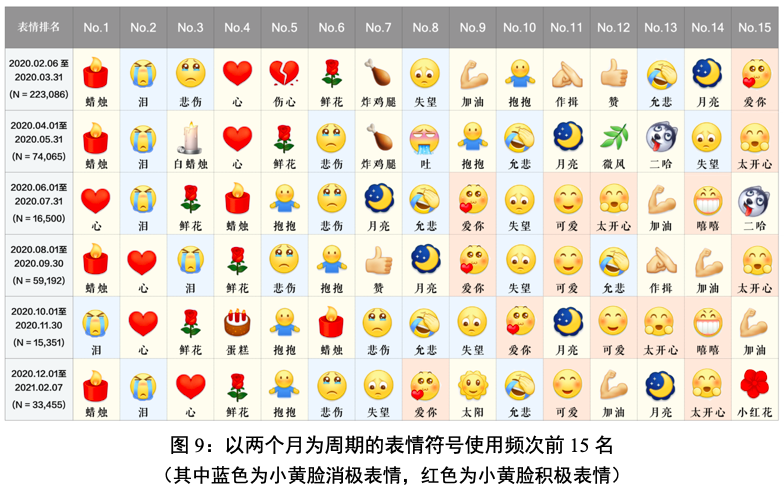

31.4% of comments included emojis. The 10 most used emojis were:

- “candle” (395,771 times, 39.6% of all emojis)

- “tears” (272,698, 27.3%)

- “heart”

- “depressed”

- “flowers”

- “brokenhearted”

- “hug”

- “fried chicken” [Li’s favorite food]

- “white candle”

- “hopeless”

Graph 4: Top 40 emojis used—candles signify grief.

To analyze the emotional tenor of the comments, we used the LIWC dictionary (Zhang Xinyong, 2015) to run an emotion recognition program that labeled posts either positive, sad, angry, or worried, with a separate group of posts labeled neutral. In the week after Li’s death, “sad” was the leading emotion, comprising 70.1% of posts (74.2% when “neutral” posts were removed). As words like “add oil (fight on)”, “respect”, “good night,” and “good morning” appeared, “positive” posts began to overtake “sad” posts. However, during special occasions, for example Li’s designation as a martyr in early April 2020, “sad” posts retook their place over “positive” posts. On the anniversary of Li’s death, “sad” emotions and “positive” emotions stayed equal. Negative emotions like “anger” and “anxiety” reached high points after Li’s death in February 2020 and the retraction of Li’s admonishment notice in March 2020.

Graph 5: Daily comments arranged by emotion expressed: positive, sad, angry, worried, and neutral.

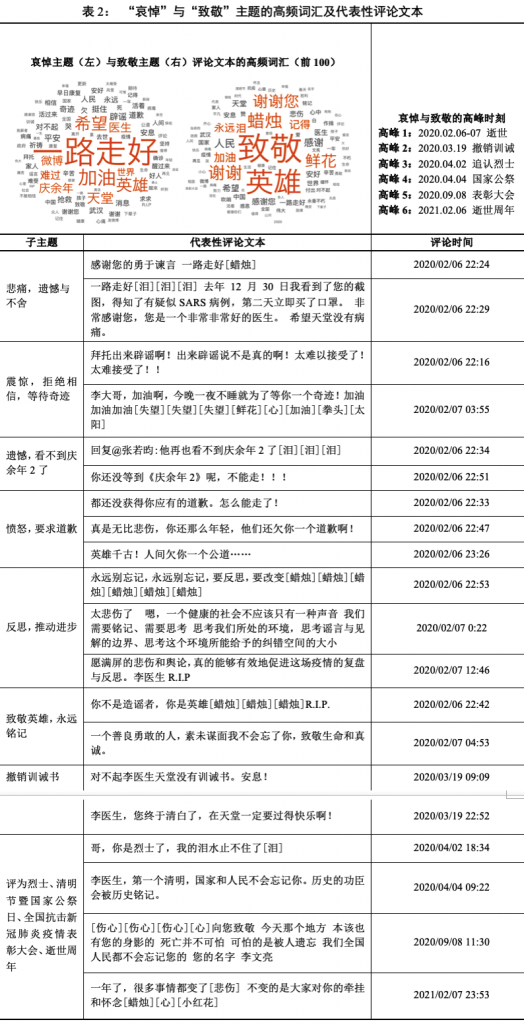

We analyzed a representative selection of posts (13,432, 1% of the total) to divide comment topics into seven main categories:

- mourning

- paying respect

- updates on the progress of events

- daily greetings and reflections

- holiday or anniversary greetings

- confiding [feelings and personal issues]

- interacting with other netizens

Chart 1: Categorized comment topics and their prevalence. (1) mourning (37.95%), (2) paying respect (8.10%), (3) updates on progress of events (3.86%), (4) daily greetings and reflections (20.38%), (5) holiday or anniversary greetings (4.82%), (6) confiding (16.17%), and (7) interacting with other netizens (8.72%).

Graph 7: Comment topic totals over time: mourning, paying respect, updates, daily greetings and reflections, holiday or anniversary greetings, confiding, and interacting with other netizens.

Comments “mourning,” “paying respect,” and “updates” were quite numerous in the two months after Li’s death, but gradually began tapering off in April 2020. There was a resurgence of such posts during three of the eight comment peaks: the September 2020 National Meeting to Commend Role Models in China’s Fight against COVID-19, the 2020 winter solstice, and the anniversary of Li’s death in 2021.

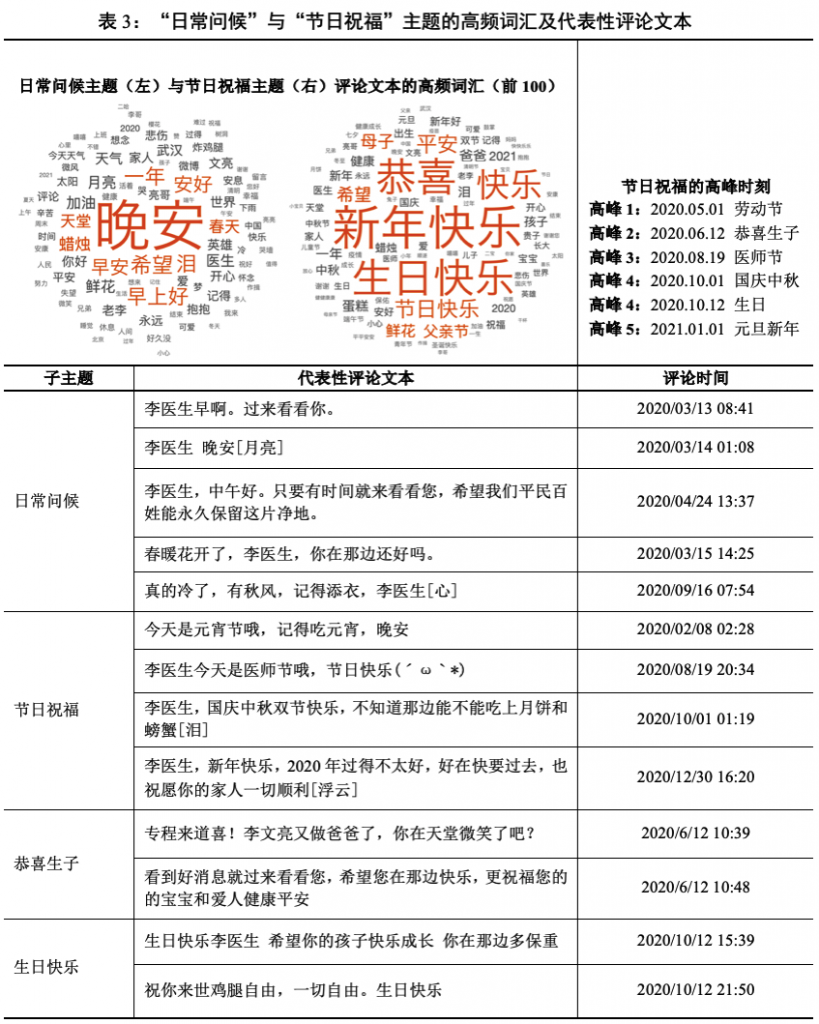

Comments categorized as “daily greetings,” “confiding” and “interacting with netizens” showed the opposite trend, steadily rising from March 2020 and later staying steady at high levels. “Holiday wishes” was the least common category—but, predictably, peaked on special occasions.

The rest of this paper will focus on the analysis of specific mourning “hot spots” while analyzing the rise of “daily greetings,” “holiday wishes,” “confiding,” and “interacting with netizens” as special characteristics of “extended affective spaces.”

During the last day of Li’s life, his final Weibo post rapidly became a central meeting point for netizens. Like a boat propelled by a flood, 360,00 people left over 40,000 comments. Collective emotional expression and individual feelings of grief fed off of each other, turning the comment section into a Weibo “miracle” and kick-starting this important space for collective internet mourning. Comments from those two days accounted for 76.6% of the entire year’s “mourning” posts—“sad” emotions were dominant, accounting for 82.9% of comments, as well as 60.0% of the “sad” emotions expressed over the year. Likewise, over 90% of the year’s “Rest In Peace” posts were made that night. Comparatively, posts containing the emojis “candles” and “tears”—which express mourning and sadness, respectively—made up 55.2% and 77.1% of those emoji’s yearly use, again respectively.

In the discourse particular to mourning, semantic network analysis reveals a representative semantic network: “deny the rumor,” “Weibo,” “resuscitate,” and “survive,” “wake up,” and “miracle.” Note after note in the comments came from netizens unwilling to believe the news of Li’s death and hoping for a miracle. They requested that Weibo quickly refute the rumor, demonstrating netizens’ shock and disbelief at the news of Li Wenliang’s death.

A second semantic network includes the terms “Qing Yunian” (“Joy of Life,” a TV drama) and “won’t be able to see this.” Before his death, Li Wenliang posted about his love for the show “Qing Yunian” (and his excitement for the new season). After posting his diagnosis on February 1, the show’s lead actor, Zhang Ruoyun, wished Li a speedy recovery. On the night that Li passed away, a number of netizens responded to Zhang’s post, “He won’t be able to see this.”

Another semantic network from that night: “owed,” “apology,” “Wuhan,” and “Public Security Bureau.” Before his death, Li Wenliang posted his admonishment notice—Wuhan police admonished him for “spreading rumors” about COVID-19. Li did not receive an official apology or explanation before his death. A number of commenters expressed rage and regret that Li had not received an apology before passing away, and hoped that this would trigger reflection and improvement in the future.

Relatively “positive” posts accompanied expressions of mourning during the high point of commentary following Li Wenliang’s death. The most common words were “respect,” “hero,” “thank you,” and other expressions of respect and thanks. At the same time, a number of phrases like “bear in mind,” “won’t forget,” and “remember forever” appeared, among other phrases stressing remembrance and rejecting amnesia. Where they differ from mourning is that expressions of respect and thanks tend to continue for a longer period of time and in a more diffuse manner. A large number of netizens expressed these emotions during important events, like the retraction of Li’s admonishment notice on March 19, his designation as a martyr on April 2, Qingming Festival and the National Memorial Day on April 4, and the September 8 National Meeting to Commend Role Models in China’s Fight against COVID-19.

Chart 2: Common phrases in comments about “mourning” and “respect.”

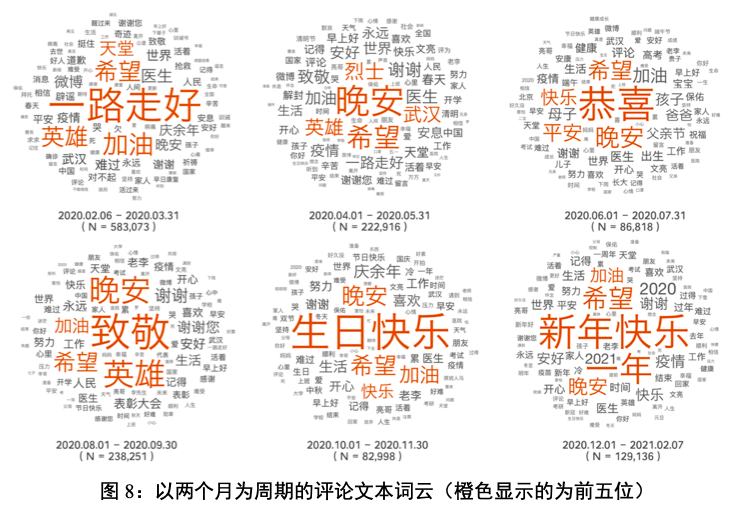

Our analysis found that April 2020 marked a clear dividing line, after which mourning, respect, and updates gradually diminished as daily greetings, holiday wishes, confidences, and interactions with other netizens increased. The word clouds below show that in the two months after Li’s death, most topics concentrated on mourning and remembrance. Between April and May, the most common word became “good night,” which remained one of the most popular until the end of the study in February 2021. As time went on, positive emotions, represented by red words and yellow emojis in the charts below, grew noticeably (especially after the birth of Li Wenliang’s son in June 2020).

Graph 8: Word clouds over two month increments. February-March 2020 in the top left, moving left to right until December 2020-February 2021 in the bottom right.

Graph 9: Emoji use over the course of this study. Each row shows the 15 most frequently used emojis during a 60-day period, starting with February-March 2020.

Chart 3: Common words in comments on “daily greetings and reflections” and “holiday or anniversary greetings.”

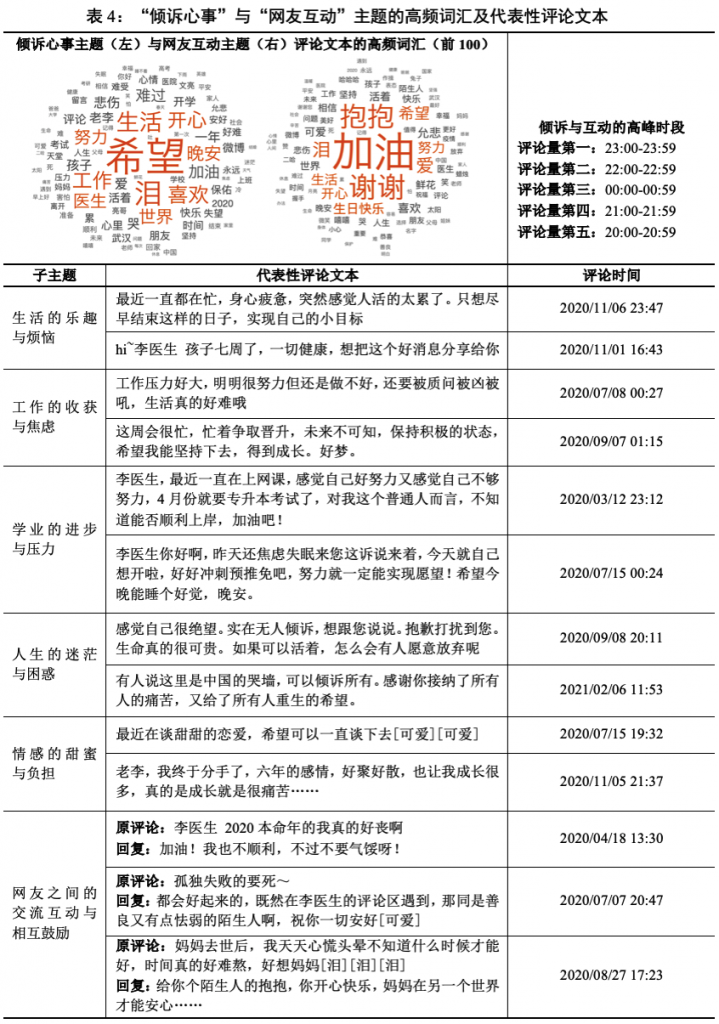

Possibly because this community of mourning created an atmosphere of kindness and tolerance, people gradually began to speak about their own life, study, work, and emotions, as well as their troubles and frustrations. People came to the comment section to share good news about their life with others in the comments. In a departure from previous findings (Blank, 2009), commenters in Li’s comment section didn’t solely converse with Li Wenliang, they also interacted with each other—creating new emotive spaces.

In total, 87,419 comments received responses from strangers (6.5% of total comments). 37,370 of those were responses to “confiding” comments (42.7% of responses from strangers). Among all the comments responded to by strangers, 12,930 included question marks. This demonstrates that when netizens shared their joys and fears in Li Wenliang’s comment section, they anticipated encouragement, help, or solutions from other netizens.

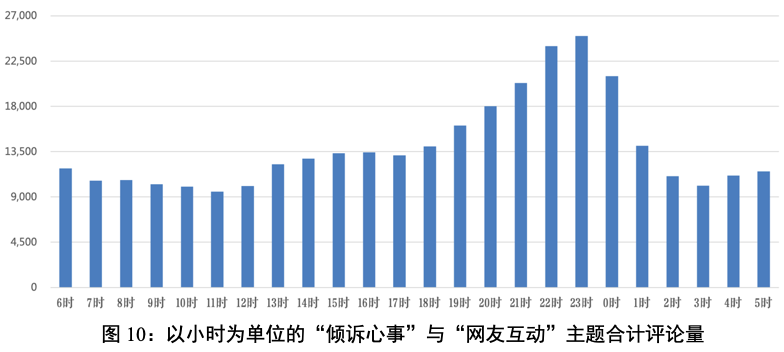

Graph 10: Time distribution of comments related to “confiding” and “interacting with other netizens.”

Chart 4: Common words in comments on “confiding” and “interacting with other netizens.”

In traditional Chinese culture, the “tomb keeper” is an important emotional symbol that exemplifies faithfulness, belief, and righteousness.

Social media has structured communities of mourning into “mobile” frameworks. In the course of our research we found that 668,096 commenters (~86% of the total) left only a single comment—they were “passers-by.” However, there were 1,316 people who commented for 30 days or more, leaving a total of 133,914 posts. Although these users account for less than 2% of total commenters, they contributed 10% of total comments. One hundred and three people commented for over 100 days. One person commented on 190 of the 368 days covered in our research. There were not hurried “passers-by.” Instead, they became social media’s “online tomb keepers.” The rest of this paper will focus on “passers-by” and “tomb keepers”—comparing the habits, substance, and user profiles of the two groups.

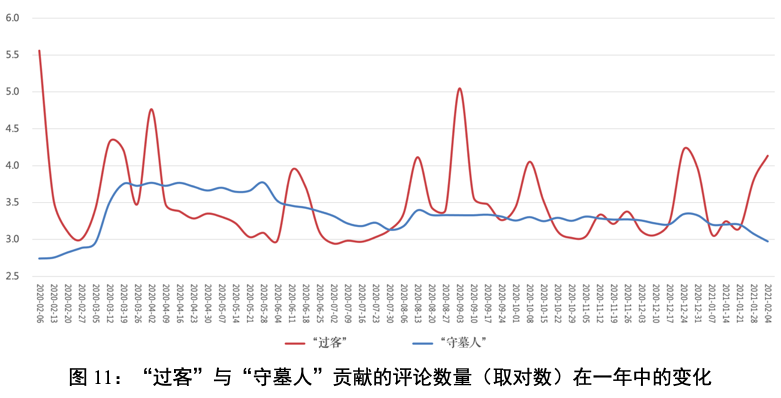

Graph 11: Comment totals by “passers-by” and “tomb keepers” over time. Red=“passers-by”, Blue=“tomb keepers”

When comparing comments by “passers-by” and “tomb keepers” over the course of the year, it becomes obvious that “passers-by” react on impulse to breaking news in a distinctive wave pattern, whereas “tomb keepers” were comparatively unaffected by breaking news—their comment numbers stayed steady throughout the year.

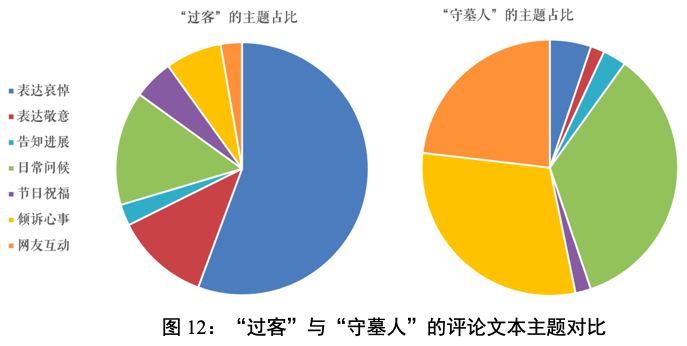

Graph 12: Themes in comments by “passers-by” (left) and “tomb keepers” (right). Dark Blue= mourning, Red=respect, light blue=updates, green=daily greetings and reflections, purple=holiday or anniversary greetings, yellow=confiding, and orange=interacting with other netizens.

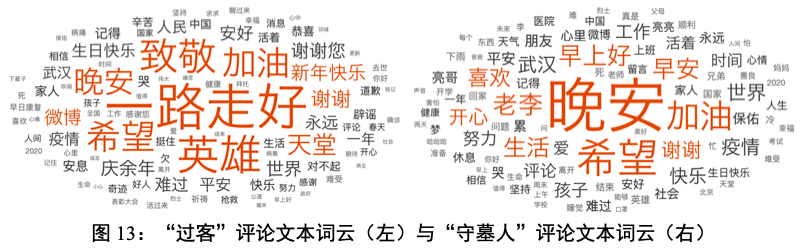

Graph 13: “Passers-by” word cloud (left) and “tomb keepers” word cloud (right).

There are no significant differences in geographical location between “passers-by” and “tomb keepers.” The gender disparity among “tomb keepers” is 57.1% men and 42.9% women, whereas “passers-by” are 64.2% women and 35.8% male. Compared with the gender disparity among total commenters (63.3% women, 36.7% men), more women participated in Li Wenliang’s comment section as “passers-by,” whereas more men decided to stay, transforming themselves into Li Wenliang’s Weibo “tomb keepers.”

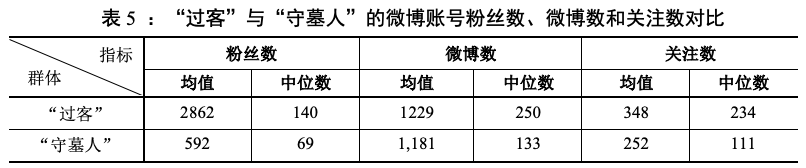

Chart 5: An analysis of “passers-by” and “tomb keepers” Weibo follower counts.

On average, “tomb keepers” had fewer Weibo followers than “passers-by.” One may infer that their community is one with comparatively weak influence and low participation rates. Accordingly, Li Wenliang’s Weibo comment section has become a unique and precious space for them to exchange greetings, share their feelings, and encourage each other.

Summary: Online Mourning, the Affective Public, and Historical Memory

Li Wenliang’s Weibo comment section reflects the fundamental characteristics of online mourning in the social media era. Social media forms the space and expression of public grief by expanding the scope of collective emotional experience (which is no longer restricted to personal relations) and mobilizing a collective of people with different social backgrounds to express their sadness together. In the course of this process, social media constructs the ideal circumstances for an extended space-time, providing an important space for emotional expression. Li Wenliang as a figure became a gathering point for the public’s emotional reaction to the unique circumstances of the pandemic, and an important component of citizens’ expression and participation. The atmosphere of community created by explosive collective online grief, the proliferation of the “Wailing Wall” phenomenon, the interaction, absorption, and adjustment that took place between the state, internet platforms, and the public conscious, and the strategic respect for “symbolic marks,” jointly influenced this specific case, revealing its exceptional qualities.

The core trait of the collective mourning and extended affective space in Li Wenliang’s Weibo comments was emotional expression and exchange. The brevity of comments doesn’t allow for complex logic, yet serves to reveal the public’s emotions. This affective space has two attributes: (1) Li Wenliang’s treatment and death incited intense feelings of pain, sympathy, rage, and justice. The public’s sympathy and pity for an ordinary, good person, and their calls for a more just society, are stabilizing emotional structures in Chinese society (Williams, 1977). (2) The “tree hollows” created by the extended affective space provided countless ordinary people a place to confide their feelings and personal issues, encourage each other, and express love, support, and solidarity. In the comments, ordinary people shared their troubles, joys, and pains in school, work, love, and family, their desire for a good life, and their hope to be understood and supported, coalescing into a new structure of emotional resonance. It is precisely the understanding and goodness of the mourning space that provides the opportunity for this expression, and it was this powerful expression which protected and extended the space for the community of mourning. How could society function without such a space for emotional expression? It is with this in mind that we may say Li’s Weibo comment section has molded a unique affective public (Papacharissi, 2015): created around the passing of a specific person, connected through social media, and centered around the expression of emotion (not opinion) to form an open, collective, communicatory, mobile group. Their narratives are the stories of this era; their emotions refract the emotions of the era.

The formation of this affective public is also an effort to preserve historical memory. Traditional mourning and remembrance is temporary; social media provides a juncture to preserve both emotion and memory. As fall turned to spring, and as the public recorded their mourning and grief for Li Wenliang, they also wrote about their own joys and worries: “Earth suddenly reports the tiger subdued,” “In your ancestral sacrifices/Forget not your brother.” Netizens’ collective writing stands outside of the bureaucracy and the media, creating a unique memory of the lives of ordinary people in extraordinary times. [In general,] private, daily practices of “etching [events] into memory,” “refusing to forget,” or “checking in” all indicate a conscious effort to reject amnesia and preserve memory. This reservoir of memory is pushed forward by emotion (Levine & Pizarro, 2004). Because of this, Li’s Weibo comment section has not only provided the space to form a unique affective public, but has also given rise to a new written experience of collective memory in the internet era.

“What more is there to say on death, send the body to its mountain peak.” Social media has become the structure through which emotion is conveyed to the deceased and a place of spiritual comfort for ordinary people. An ephemeral moment becomes an eternal memory. Over the course of our year-long observation, we witnessed this evolution. How this unique community of mourning and “extended affective space” will develop in the future is worth continued observation over the coming years.

This paper used computational communication methods to analyze data and record the words, themes, and emotions of internet users’ comments. We also combined the data with the specific language of netizen expression, revisiting the words of ordinary people as a method of preserving memory. Behind this data lies humanity, warmth, and love. We wish to devote our computational communication research to the public.

Post by Samuel Wade and Joseph Brouwer; translation by Joseph Brouwer, John Chan, and Anne Henochowicz; CDT’s Wailing Wall archive, and selections here, compiled by Tony Hu.

No comments:

Post a Comment