Distressed at the dearth of civic understanding in the United States, Ed Hagenstein worked for over two decades to create The Language of Liberty: A Citizen’s Vocabulary. Its purpose is simple: the constitution demands consensus and our form of government requires discourse, which depends in turn on a precise and nuanced vocabulary of its own. Hagenstein has set out to recover 101 words that are essential to the American experiment, many largely lost to disuse or misuse.

Billed by its author as “an owner’s manual for American citizens,” the book takes its readers through 101 political terms that Hagenstein thinks any citizen needs to understand in order to actively and intelligently participate in civic life. The Language of Liberty provides definitions that are clear, direct, and stripped of partisanship, but the work is more than a lexicon. Hagenstein explores each term in the context of American political life and history, providing unexpected insight into even the most recognizable terms. Governing.com Editor-at-Large Clay Jenkinson recently spoke with Hagenstein about his book and the current state of civic understanding. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Source: Ed Hagenstein

Governing: Our civic culture appears to be in disarray. The average American would not understand much that's in your book, and even fairly well educated Americans would make a lot of mistakes. How bad is America's civic understanding?

Ed Hagenstein: It's very bad. It's been bad at least since I was in high school. When I was about 22, I thought I knew everything about politics. I was happy to spout off. At some point I became aware that what I thought of as being politically informed really just meant that I had a grab bag of opinions about issues of the day. I realized at some point that I knew almost nothing about what was in the Constitution, let alone its underlying logic. That was four decades ago now, and I went to what was considered a very good public high school outside Boston. So it's been going on for a while. I do fear the trajectory we're on. John Adams said that the founding generation, the whole American population, more or less imbibed constitutional thought with their mother's milk. Everybody had a constitutional understanding. The Constitution was out in the populace before it was written in Philadelphia. It’s a daunting task to recreate that sensibility.

One of the things about the constitution, of course, is that it's there in a sense to frustrate us ...

Governing: There’s a sense now that the American people don't mind not being civically intelligent, and yet they have strong opinions about such matters in every direction.

Ed Hagenstein: That's right. One of the things about the constitution, of course, is that it's there in a sense to frustrate us, and nobody wants to be frustrated. We have a government that's structured around the idea of discourse and reaching some kind of a consensus. That demands that we acknowledge other people as having legitimate points of view and trying to work with that. At a time when the country is huge, 330 million people, and extremely diverse, consensus is really hard. It's frustrating to knock your head against the wall trying to convince others. A lot of people don’t feel compelled to engage in that way, yet that's what has to be done.

Governing: The events of recent years suggest that our lagging proficiency in civics is far more dangerous than simple public stupidity. When Barack Obama was legislating largely by executive order in his second term, why wasn't there more nonpartisan outrage at that violation of the Constitution? Then Donald Trump took it in a much graver direction. Shouldn’t people have stood up to them, irrespective of their party affiliations, and said this is not good for our country?

Ed Hagenstein: I wish there were more voices out there saying that. It's frustrating watching the executive order. I regret that I didn't include it as a term in the book. What’s going on now is no way to govern, and they’re doing this on some serious issues. We've always had executive orders, which are probably necessary for running the executive branch. But for determining something as important as immigration, it’s not a healthy way to govern.

Governing: It seems that if we really understood your book, we would do everything in our power to maintain a republic. The other possibility is that a republic can't govern a nation of 340 million and a world of cruise missiles and cyber terror. If we’re adjusting towards a post-republican world, it wouldn't do us a lot of good to get prickly about war powers and executive orders and such. What do you think?

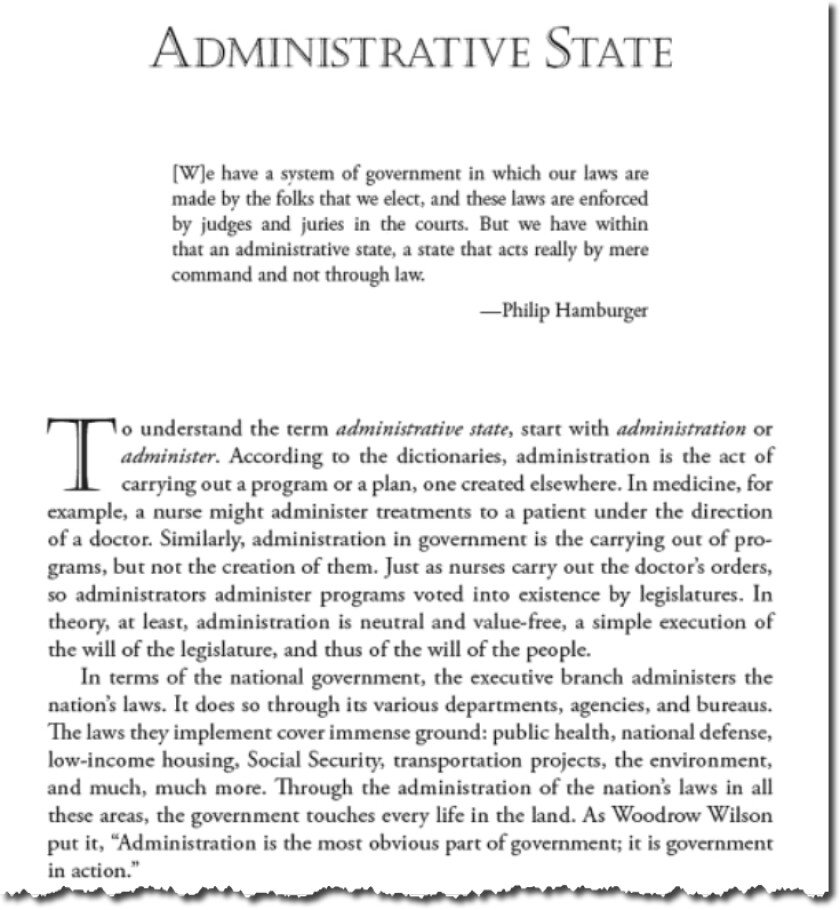

Ed Hagenstein: I'm of two minds about that. Adrain Vermeule, a constitutional law professor at Harvard, says that we evolved away from the Madisonian Constitution during the 20th century with the development of the administrative state, and there's no going back. He contends that it's not necessarily a bad thing, that it's been an organic transition to this point. I see his point. I can understand there is probably no going back. But I want to hold on as much as possible to some of the aspects of self-government. None of us have a whole lot of control over what happens in Washington. But I want to hold on to as much control as we can over our lives, to not feel that we're at the mercy of obscure powers that descend on us from who knows where. I want to hold on to the notion of a citizen as somebody who does, in fact, have some sort of say over how he or she is governed.

Governing: Do we no longer agree on a set of norms? Do millions of Americans just want their point of view to dominate, even if it rides roughshod over the Constitution?

Ed Hagenstein: I'm afraid so. I don't necessarily blame Trump and his administration. It's a symptom of a deeper problem, of some sort of disruption in our civic life that goes back quite a way. A scholar named Samuel Huntington wrote a book on the issue of national consensus called Who are We? He made a point that has stuck in my mind ever since. He said that if you ask anyone over a certain age, maybe 40 or 45, about the American way, everybody knows what you're talking about. They would all define it in more or less the same way. But if you ask anyone under a certain age, and it might have been 30, you get exactly the opposite. You get nothing but blank stare, head shaking, what on earth are you talking about? I'm at the age that I can't remember something like the American way being talked about when I was a kid. It really did disappear at some point. There is something very serious there, a real disruption in terms of the Constitution and the American system as a whole.

Civic Illiteracy as a Casualty of the Speed of Change

Governing: What do you think it means?

Ed Hagenstein: It seems partly to be an international thing. It's not just us suffering through this. You get a sense from the news from Great Britain and France and elsewhere in Europe. It's a broad matter, but I can put it in an agrarian context. Since the industrial revolution, we've been on an accelerating path of change. We're not really used to that. I'm not even sure humans can live naturally with so much change. In writing the entries for The Language of Liberty, I often found myself going back to the late 19th century, to the huge challenges we faced then and the governmental response, the Progressive movement, the rise of the presidency into a more powerful institution than Congress, and various other things. The rise of the administrative state and regulatory agencies. All of that to me was a response to massive industrialization and huge changes in how we lived.

Governing: One argument is that we are living with an 18th century Newtonian constitution, designed for a three mile-per-hour world, that it doesn't really work in this universe.

Ed Hagenstein: Woodrow Wilson said you can't look at a Newtonian constitution through a Newtonian lens. You have to use a Darwinian lens, and the Constitution has to evolve or die. I’m a little reluctant to agree with Woodrow Wilson, but I see his point. With the massive changes that came with industrialization, the mass immigration and urbanization, it's tough to imagine that we wouldn't respond somehow. And it doesn't seem unnatural that we've evolved the way we have constitutionally, with the administrative state and regulatory powers and all that.

Governing: It would be difficult for a reader of The Language of Liberty to discern your politics, which is a rare and good thing. But is it fair to say that there is a lot of the Jeffersonian in what you say in the book?

Ed Hagenstein: That's fair. I’m attracted to the agrarian tradition and more comfortable there than with the Hamiltonian tradition. A man named Leszek Kolakowski wrote an essay titled “How to be a Conservative Liberal Socialist: a Credo” that was especially important to me in forming my mind for the book. I find it very easy to be all three of those things at once. My politics are all over the place, and I'm glad they seem hidden. But I do have a strong attraction to the Jeffersonian and agrarian heritage.

Teetering Between Failed State and Getting By

Governing: Are we a failed state, or are we doing pretty well?

Ed Hagenstein: Somewhere in between. We're going to be facing storms somewhere in the future. I end my entry on conservatism by talking about ordinary, day-to-day conservatism. The habits of people who get up and go to work and do their thing and treat their neighbors well and do all that. We’re in for some stormy constitutional weather ahead, and it'll test us. Whether the constitution holds and whether we remain a constitutional people is an open question. An awful lot depends on our leadership, which has not been good, and I don’t just mean in the political sphere. But I trust that the American people have pretty terrific reserves of decency and regard for others and for lawfulness. Some of that's dissipated over the years and over the decades, but there are real reserves there.

Governing: Archimedes said, “Show me where to put the lever and I'll move the world." Where would you put the lever? Where could we gain the most ground?

Ed Hagenstein: My mind keeps coming back to legislatures. We've seen a deterioration, certainly at the national level, of the strength of Congress in relation to the executive branch and the judicial branch. But there's something that a legislature has that the other branches don't. It’s comprised of the representatives of the people. You've got all these people in the country who are fighting mad. Take their representatives and lock them in a room and tell them they have to talk to each other. I consider legislatures as places of discourse and compromise. It can't happen without engaging other people, and legislatures are where opposing points of view are expressed and discussion has to happen. Debate is built into the Constitution and into the rules of the House and the Senate. Maybe it’s with legislators that we might place a bit of hope.

You can hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour, and the new Governing podcast, The Future In Context.

No comments:

Post a Comment