The stories present, to a large extent, the dark worlds of lonely characters experiencing varying degrees of tragedy, depicted through a bleak and straightforward language.

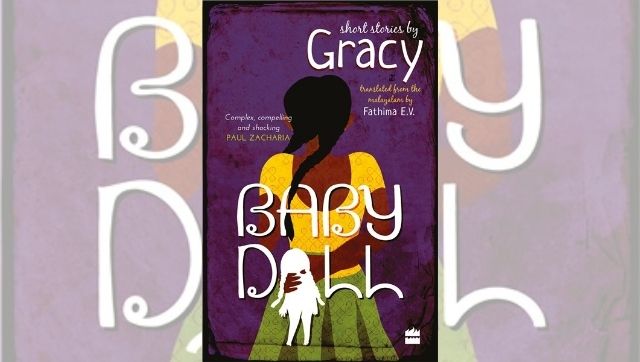

Gracy’s Baby Doll: Stories is an exemplary affair with loneliness; and an arduous lockdown read. Translated from the Malayalam by Fathima EV, they present, to a large extent, the dark worlds of lonely characters experiencing varying degrees of tragedy, depicted through a bleak and straightforward language. Written across three decades of her career and arranged chronologically, they present loneliness as an abiding force, one that can often result in mental instability. For instance, in Arundhati’s Dream, the protagonist is afraid of falling asleep because of her vivid, terrifying dreams. In Cat, the narrator is convinced that his wife, who has cat-eyes, is a cat herself and has been impregnated by the tabby hanging around outside their house. And in Panchali, Krishna learns that her husband enacts the five Pandavas each night in the bedroom until she decides that like with Draupadi, instead of her husband, someone else must come to her rescue.

Instead of allowing empathy between women, the mother-daughter relationships are also often strained. “You have vengeful mothers and daughters who refuse to forget what has been done to them,” says Fathima. An example of this is the story Illusory Visions where a woman sees coffins and on opening them, speaks with her deceased parents. The conversation steers into bickering and fighting until her mother curses her: “Just wait, you will pay for this.” And soon after, a car arrives with her husband’s body. In What Mother Ought to Know, a woman’s rebellion lies in wearing a bright red sari to her mother’s funeral. “In a Gracy stories, life seems to be horrendous even for children in most cases,” adds Fathima. A prime example is the titular story, where the daughter, who loves dolls, is lured away by her neighbour into his bedroom in exchange for a living doll.

“These are all intimate portraits of people. She’s talking about lonely people caught in the web of deceit and adultery, complex human dynamics, and familial and marital problems,” says Fathima. Sometimes it seems as though she’s about to embark on a new strand of thought, like alternative sexualities and the undercurrents of a homosexual relationship in Parting with Parvathi. But such routes are never fully developed, and the reader continues to exist within the same, flustering world, where "there are no comforting things to fall back on".

The sense of loneliness pervading the book’s pages is aided by her use of language. Gracy, says Fathima, often “adopts a conscious distance and indifference” in her writing, a language that’s used strongly to create an atmosphere.

Everything is laid down clearly in front of the reader and emotion stems from the lack of escape from the characters’ stifling private worlds.

Complementing this use of language is often a dark or acerbic humour, another common thread through much of her writing. At other times, her writing can also employ a “disarmingly playful” tone and create spunky characters like Orotha in ‘Orotha and the Ghosts’ who talks easily with the ghosts hanging around and awakened by the wind. And while there are constant references to Hindu folklore and mythology, Gracy’s stories also "draw upon a strong Christian ethos".

While thematically the stories present several strands, from loneliness to religion and from mental health to the intrinsic nature of human beings, Gracy is recognised largely for her depiction of women. In the early days, she attracted attention and controversy because of her candid portrayal of sexuality and female desire, especially when she was connected with Pennezhuthu, the women’s movement. They foregrounded writing about women and female desire, and discussed fundamental issues like gendered perceptions, patriarchal ideologies, and "the rampant misogyny which is there in Kerala’s cultural fabric". After the movement slowed down, Gracy preferred to stay away, not really aligning with any other movement or collective. “It was an isolated path that she preferred.” But her concerns remained the same, largely reflecting the issues that society around her is tackling. “Because the situation has not changed fundamentally, Gracy still continues to write about those things, so of course there’s some repetition.” However, in other ways, “Kerala’s social fabric is changing, and Gracy’s recent stories reflect the concerns of the changing demographic, accommodating migrant workers and other marginalised characters into her fictional terrain.”

With a range of themes and characters between the covers of the book, Fathima successfully challenges the assumption that Gracy only writes about women, it being her primary goal in undertaking the translation. “Of course, in any translation there are going to be semantic and cultural difficulties. But I’ve read a lot of her stories and she’s been really generous with her help,” says Fathima about the process. When translating, while ensuring clarity was most important for English language readers, in some instances, especially where an atmosphere is strongly evoked, Fathima found a deliberate lack of clarity. Translating then meant working closely with Gracy so she could clarify things where needed, the translating process becoming an intimate collaboration between the two. “Translation is like an extended authorship. It’s a collaborative act between the reader, translator, and writer,” says Fathima, who’s previously also co-translated Delhi: A Soliloquy.

“I think translation offers a chance for writers to revisit their work, edit and reassess it, and give editing another go,” she adds. However, this opportunity for reassessment is lost with the recent trend of publishing translations with or soon after the book is published in one language, among the recent trends she’s noticing across the Malayali literary landscape. “Once upon a time we had an incubation period. The book would get to the reading public and establish itself before requiring or demanding a translation.” Now, it’s the writers who demand translations. “Is there a selection process involved? I don’t know.” With no incubation period and more accessibility to translators, more books are coming out in multiple languages. Whether that’s better or worse for Malayali literature is yet to be seen, “though the focus on translation by publishers and readers certainly bodes well for Malayalam.”

No comments:

Post a Comment