The School of International Letters and Cultures hosted a conference in November, sponsored by Arizona Humanities and Arizona State University, about the theory and practice of translation and interpretation.

“Engaging Translation: Questions of Language and Power in Arizona and Beyond” was held on ASU’s Tempe campus Nov. 12–13. Attendees included professors, students, translation professionals and other community members. The conference’s program included individual presentations, keynote addresses, panel discussions and workshops.  The panelists and moderator stand together on stage before their discussion on language and power in Arizona as part of the two-day "Engaging Translation" conference held on ASU's Tempe campus. Photo by Tim Trumble Download Full Image

The panelists and moderator stand together on stage before their discussion on language and power in Arizona as part of the two-day "Engaging Translation" conference held on ASU's Tempe campus. Photo by Tim Trumble Download Full Image

The two-day event concluded with a panel moderated by Fernanda Santos, a Southwest Borderlands Initiative professor of practice in ASU's Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. The discussion featured federal public defender Milagros Cisneros, Valencia Newcomer School Principal Lynette Faulkner, The Welcome to America Project Agency Director Mike Sullivan, ASU’s American Indian Studies Director Stephanie Fitzgerald and ASU’s Center for Latina/os and American Politics Research Director Rodney Hero.

The professionals on the panel talked about the various ways language has been used by and against the communities they work with. For example, Sullivan discussed how the refugees served by his nonprofit are supported upon arriving in the United States. The organization’s goal is not for the refugees to assimilate into their new communities, but for them to integrate and interact so that they can experience their new language and culture while continuing to celebrate and share what is familiar to them.

“You’d be surprised how a simple word can open up a door and relax a setting,” Sullivan said.

Similarly, Faulkner described how the multilingual students at her school – which serves young immigrants and refugees who are new to the U.S. educational system – and their families are reassured that their native languages and cultural heritage won’t be swept aside as they learn English and make a new home in the U.S.

“Their culture is strong, and it is celebrated,” she said, noting that in the students’ interactions outside of class, they share their native languages with each other while relying on English as a common tongue.

Fitzgerald connected this to her work at ASU, whose American Indian Studies program includes classes on the Navajo and Oʼodham languages. Many students come into the program unfamiliar with these languages as a result of governmental and educational policies that punished students for not speaking English and displaced Indigenous people from the communities where their ancestors had lived.

Having the opportunity to learn their native languages, Fitzgerald said, “is immensely rewarding, and it provides this emotional connection. It’s beyond words to be able to recapture something that was not available previously.”

All of the panelists agreed that language offers an ability to bridge gaps in society and connect groups of people, whether they are alike or different.

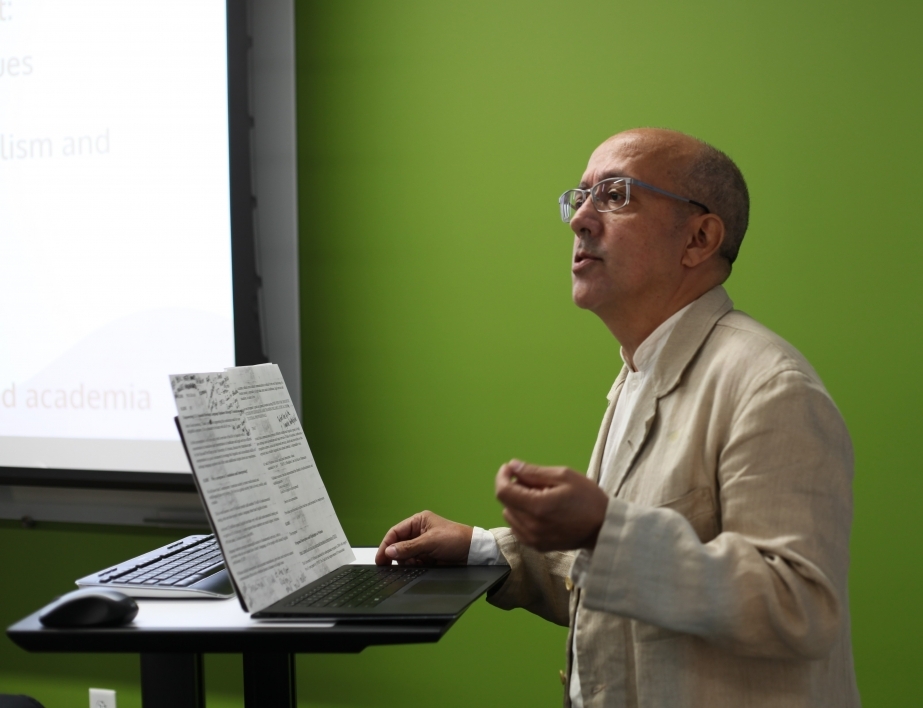

Earlier in the day, several School of International Letters and Cultures professors participated in some of the conference’s concurrent panel sessions.

Associate Professor of Japanese William Hedberg gave a talk on “Meiji-Period Translations of Chinese Narrative into Vernacular Japanese” during a session on “Sacred and Vernacular Languages in Asia” that put his work in conversation with that of several scholars from around the world. And Assistant Professor of French Isaac Joslin presented his research on “Multi-Lingual Poetics: Mediating the Mind in Francophone Africa” as part of a session centered on “Orality, Narrativity and Translations of Afro-Diasporic Thought.”

Both their presentations engaged with the tensions between languages when texts are translated from one to another to reach a target audience, or when pieces of one language are included in texts written in another tongue. The question of audience is a long-standing one for African literature, Joslin said, although perhaps not the most important factor for writers to consider.

“Rather than focusing on one’s public, whether one is writing for a global or a local audience, the question should address first and foremost the author, who writes for him or herself as a means of expressing his or her memories, thoughts, emotions and reflections on life,” Joslin said. “The question that follows then is which language is best for accomplishing this feat, again, regardless of the potential audience.”

This emphasis on language as, above all else, a powerful tool for self-expression was underscored in many of the presentations throughout the conference. It is clear that language inflects many facets of everyday life, from conversations with friends and family, to interactions in legal or medical settings, to experiences in educational and governmental environments.

No comments:

Post a Comment