One day last month I was standing in line at my neighborhood gas station with a six-pack in one hand and a three-day-old corndog in the other when a tall, younger (than me) Black man with a semi-automatic pistol on his hip walked up beside me.

I nodded and smiled, which he acknowledged with a micro-nod. I paid up and went out to my car.

While fumbling for my keys, I watched out of the corner of my eye as he came out and brushed by a white man about his age and build on his way in. They both turned and looked at each other, and the white man said, “What?”

The Black man said, “Harold?”

They embraced. They wept. They shouted “hooah!”

They were soldiers once. Everything they could remember about their war poured out of them like water over a dam. They wiped away more tears, standing in front of the gas pumps, clinging to each other, shouting “hooah!” over and over, beautifully oblivious to the cars maneuvering around them.

I very deliberately slowed down the fumbling of my keys to eavesdrop. I could not help absorbing what I’d feared, what I witnessed, what I felt, but I didn’t know what to call it or where to file it in memory. There’s got to be a word for this, I thought.

Where does one turn for guidance in such matters?

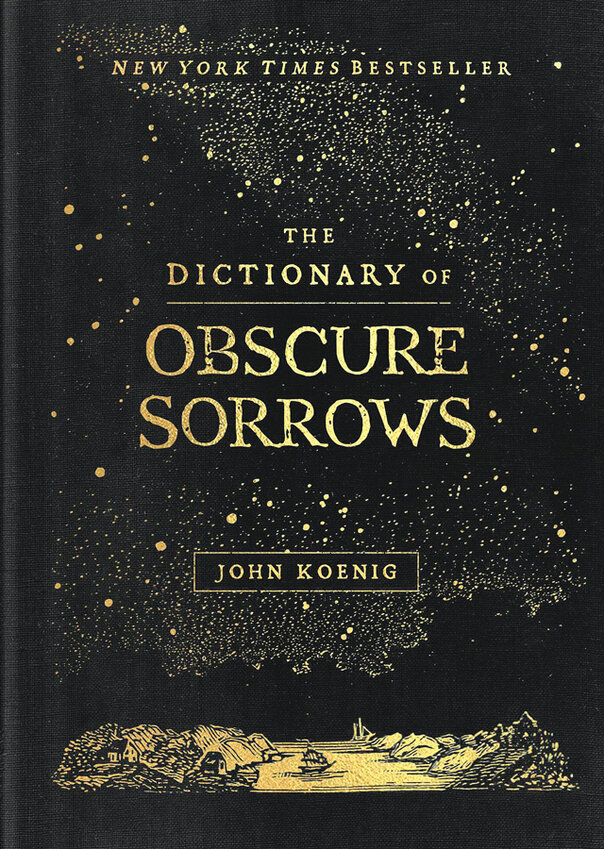

“The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows” is one gateway.

“It’s a calming thing, to learn there’s a word for something you’ve felt all your life but didn’t know was shared by anyone else,” writes John Koenig in his introduction. “It makes you wonder what else might be possible — what other morsels of meaning could’ve been teased out of the static if only someone had come along and given them a name.”

Koenig wrote this book (Simon & Schuster, 2021) over the course of a decade while working on his popular blog on the subject. It began as a peculiar whim to push against those boundaries identified by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who said, “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.”

This dictionary is a collection of invented words defining emotions many of us may have experienced but never thought to define or thought could be defined — our obscure sorrows — by turns light-hearted or tragic, and always poignant. Koenig was inspired to write the book by responses he got to his blog.

“There was the young woman in Pakistan who would observe her 96-year-old grandfather across the dinner table every night, mystified by the enormity of his life experience, so different from her own. There was a deployed U.S. Marine who secretly dreaded video chatting with people back home because it made him feel never closer but never farther away.”

Koenig’s writing is poetic, though I hesitate to use the word since there are no poems in these pages and the very word may scare off those who could benefit most by reading them.

But having said that, “It’s a poem about everything,” he writes. “These words were not necessarily intended to be used in conversation, but to exist for their own sake. To give some semblance of order to the wilderness inside your head, so you can settle it yourself on your own terms.”

And so we find such samples of shared experience as:

Apolytus: n., the moment you realize you are changing as a person, finally outgrowing your old problems like a reptile shedding its skin. (From “apolysis,” the stage of molting when an invertebrate’s shell begins to separate from the skin beneath it + “adultus,” sacrificed.)

Ozurie: adj., feeling torn between the life you want and the life you have. … Some days you wake up in Kansas, and some days in Oz. (From “Oz” + “prairie,” with “you” caught somewhere in between.)

Thwit: n., a pang of shame when an embarrassing memory from adolescence rushes back into your head from out of nowhere, which is somehow no less painful even if nobody else remembers it happened in the first place. (Acronym of “The Hell Was I Thinking?”).

Zielschmerz: n., the dread of finally pursuing a lifelong dream, which requires you to put your true abilities out there to be tested on the open savannah, no longer protected inside the terrarium of hopes and delusions that you started up in kindergarten and kept sealed as long as you could. (From the German “Ziel,” goal + “Schmerz,” pain.)

In the years writing the blog that became his book, Koenig was often asked whether his words are real or made up. He struggled with that question before finally understanding that all words are made up — “no more real than the constellations in the sky.”

“Really, that’s all a word is: a constellation of thoughts and feelings that our ancestors traced into memorable shapes,” he writes. Some took hold, some disappeared.

“The meaning of things isn’t an emergent property of how long they last. We are the ones who define them for ourselves, if only for our own satisfaction. … To the honeybee, summer never ends.”

And about what I saw at the gas station. I’m no John Koenig but once I became open to thinking like him, a new word did suggest itself to me.

Circumseizure: n., an event of startling clarity one is helpless to resist, that overrides all preconceptions and desires to change it, making room for something else to flood in. (From “circumstance,” a condition connected to an event + “seizure,” a physical attack or action capturing someone or something by force.)