PREMIUM

PREMIUM

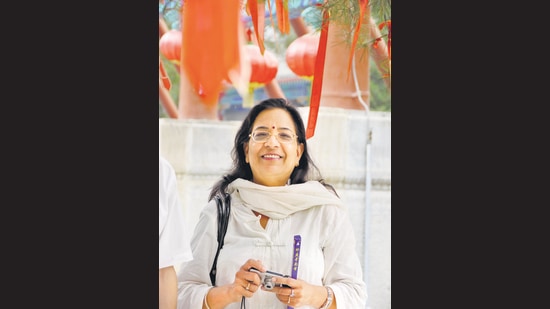

Shashi Bala, 65, has been steeped in Sanskrit for decades, and soon she’ll have a unique dictionary to show for her efforts.

The multi-volume work — one volume is being printed, two are nearly done, and there will be a total of seven or eight volumes and 3,200 pages in all — is perhaps the most extensive of her projects. But Bala has been fascinated with Sanskrit since she was 15, and began studying the language and its cultural influence across Asia, as well as contributing scholarship herself, soon after.

“I set out wanting to be a doctor, like my aunt,” Bala says, laughing. It was her father who introduced her to the work of linguist and scholar Raghu Vira (1902 - 1963). He had a printing press in Delhi and many of Vira’s books were published there.

First reading Vira’s work as a 15-year-old, in 1965, “it was just fascinating to know that the Sanskrit language had spread to countries like China, Japan and Mongolia so many centuries ago. That was how the seed of scholarship was sown in my mind by my father,” Bala says.

In college, she opted to study Sanskrit. In 1977, she began her life in research, with an MPhil project on Sanskrit grammatical texts from Indonesia.

“The research opened up a fantastic world. There is Sanskrit poetry from Indonesia, Buddhist literature, and their versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata,” she says. “According to the Vietnamese Ramayana, Rama after his victory over Ravana does not go to Ayodhya but goes to Vietnam via Thailand. The geography, flora and fauna described in this Ramayana is of these countries, not of India,” she says.

Tracking Sanskrit across the region involved some fascinating journeys. As part of the research for her PhD in Vedic deities in Japanese Buddhist art, Bala travelled to Japan. Tracing the Sanskrit and Brahmi scripts along the Silk Route in 2016, she traversed the Taklamakan desert and ended up in Shanghai. Revisiting the route that took Buddhism to Japan, she made her way through China. “I must say that the Chinese government has done stellar work in the upkeep of this history,” Bala says.

Through it all, the dictionary was waiting its turn. The entries were first compiled by Vira in the 1940s. His son Lokesh Chandra, also a Vedic scholar, was then closely associated with the project. In 2013, on Chandra’s encouragement, Bala dedicated herself to making the hundreds of thousands of entries print-ready and seeing the dictionary into publication. This involved checking, editing and reorganising the material.

Complexity was one challenge; sheer volume, another. In terms of complexity, for each English verb, for instance, Sanskrit has numerous equivalents, each with its own nuance. In terms of volume, “the material fills 114 boxes and about 300,000 index cards,” Bala says.

So far, there has been one known English-to-Sanskrit dictionary, created by the 19th-century British scholar Monier Monier-Williams. “But his purpose, his way of studying and understanding the culture that this language comes from, is very different from Raghu Vira’s and ours,” Bala says. “This project could dramatically change the way the world and India reads its ancient history and culture.” It could also make that history and culture more accessible to its inheritors and scholars in India and around the world.

The dictionary is being published by the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan foundation and will be priced at ₹1,800 per volume. Once the first print run is completed, a digital version will also be available online too.

“I am excited to be able to bring to the world the work of a fabulous scholar like Raghu Vira. This dictionary should help people trying to understand Sanskrit and its influence immensely,” Bala says.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

No comments:

Post a Comment