Terry M. Wildman first had the idea of translating the New Testament over 20 years ago. Wildman was living on the Hopi Indian Reservation and serving as a pastor on Second Mesa when he found a Hopi translation of the New Testament in a church basement. “I couldn’t find anyone who could read from it,” he says. “And it wasn’t until much later that I discovered this was true across North America—very few Native people can read in their Native languages.”

At the same time, Wildman, who was also involved with jail ministry and small group ministry as well as with the church he was pastoring, struggled to teach using existing English translations of scripture, which didn’t speak to Native people or to their cultural context. “I began to experiment by rewording portions of scripture and using that in small groups,” he says. “And the response was surprising. The men and women began to interact more, to ask meaningful questions, and to relate more to what we were reading.”

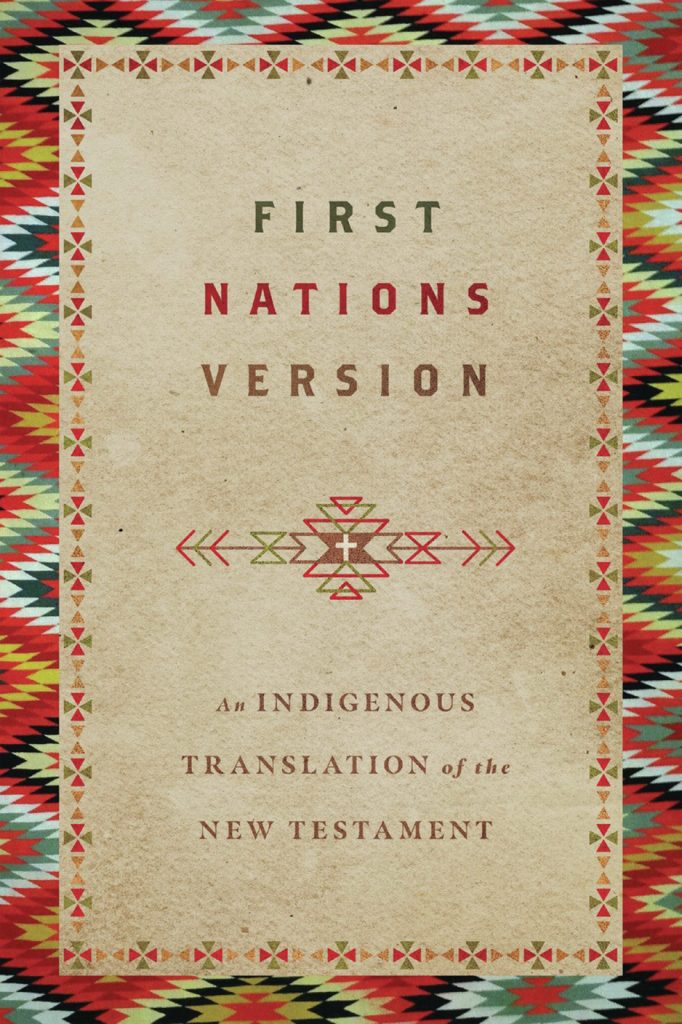

Over two decades later, this small project that began in a church basement became the First Nations Version, an English retelling of the New Testament that seeks to connect scripture with the lived out reality of Native people around North America. As the introduction to the book says, the book “is not a word-for-word translation, but rather a thought-for-thought translation.” It is the New Testament retold in language that echoes oral storytelling: “This way of speaking, with its simple yet profound beauty and rich cultural idioms, still resonates in the hearts of Native people,” the book’s translation council writes.

What inspired this project?

I guess you could say that it started while my wife and I were living on the Hopi Indian Reservation in northern Arizona, on Second Mesa. I was pastoring a small church there and wanted to have a contextual approach to sharing the gospel, or the good story as we call it.

We did a lot of jail ministry on the Hopi Rez. When I brought the New International Version (NIV) Bible we used to the jail—we used to jokingly call the NIV the “New Indian Version”—I watched how the Native people I met with responded to this version. I felt like there was something missing, a gap between the scripture and people’s experiences.

I began to search for translations that were more relevant to Native people, but I didn’t find anything. I found a Hopi Bible translation of the New Testament in the church storage room that wasn’t being used. In the five years I lived on the Hopi Rez I couldn’t even find anyone who could read it.

This is why it was really important to me to offer a Native translation of scripture in English. Ninety-five percent of Native people don’t speak their language. Of the ones who do, very few can actually read it. This is because of missionary efforts: While they were translating the Bible into our Native languages, they were also taking these languages away from us.

God blesses our Native people, who have been historically outcast, even within Christianity.

I eventually found a Native American–led organization that had done an introduction to the New Testament. In it they use different kinds of wording. They call God the “Great Spirit,” for example, and use other terminology that resonates in the hearts of Native people. I thought to myself, “Well, we need something like this.”

At first I wasn’t even thinking of a new translation. I simply wanted a new way to present the gospel. My wife and I are musicians, so we decided to create a CD, The Great Story from the Sacred Book, that included the story from creation to Christ condensed into about 15 minutes. Well, that CD became very sought after by Native people. It was our bestseller online and even won the Native American Music Award in 2009 for best spoken word production.

At this point, I felt like we were on the right track. We were expressing the story of Jesus in a Native-friendly way. From there I began to reword some of my favorite parts of the New Testament and use these rewordings in small meetings. And, again, I got really good feedback: Afterward, people would ask a lot of questions about the scripture, which had never happened before. They would say, “Oh, I understand this better now!”

But even after this, I didn’t think of doing a complete translation. It took years and years of using these small portions of scripture and getting feedback to finally convince me to work on this book, even though I felt like, “Who am I, who’s Terry Wildman, to do a translation of the New Testament?”

It was a long process. In 2002 we started getting the seeds of this idea, but it wasn’t until around 2012 that I actually committed to the process.

Often we hear that to understand scripture you need to understand the original context. But what you’re doing is the opposite: placing scripture within a unique cultural context.

Absolutely. A lot of people don’t think about this, but the New Testament is a translation from the beginning. Jesus spoke in Aramaic, so any time manuscripts have him speaking in anything but Aramaic, that’s a translation. The first time the gospel is preached it’s on Pentecost by Jewish people who are all speaking in different languages. When the apostles publicly preach the gospels after the resurrection, they don’t speak it in Hebrew but in the languages of the people to whom they are speaking. All of these are signs that God wants the good news to be spoken in other languages, because God knows how meaningful it is to hear scripture in your own language.

With the First Nations Version, it’s not actually in our native language but worded in a way that resonates with us. As one Native elder told me, “You say the words in English the way we think them in our language.” That was our goal, and it’s been so wonderful to feel like we’re reaching this goal.

What was the translation process like?

When I started working on this with OneBook Canada and Wycliffe Associates, both of which are Bible translation organizations, they encouraged me to put together a translation council.

So I started contacting people I had met from my many years of traveling all over Turtle Island, as we call North America. I was looking for Native men and women, young and old people to participate. Eventually I had gathered 12 people, and we determined how to proceed together.

There are about 185 keywords that Bible translators say you need to get right in any translation. We started with these keywords. We wanted to find words that were not from the Euro-American background of most Bible translations. We wanted them to be words that are relevant to Native people and that connect to our culture. So we translated Lord as “chief,” hell as “the Valley of Smoldering Fire,” and Jerusalem as “Village of Peace.”

After we did the initial rewording, we had teams of reviewers offer feedback using Google Docs. Everything was virtual: Yet I look back and we didn’t even have Zoom for most of the time.

Do you have a book or story that was your favorite to work on?

I was raised theologically on Paul, and I’m repentant to say that Jesus was sort of secondary to Paul in my theology: I would interpret Jesus from Paul instead of the other way around. But during this whole process I became so familiar and immersed in the story of Jesus, in what he said and how he said it, that the gospels became my favorite part of the Bible.

I loved translating the Sermon on the Mount. It’s kind of the best of Jesus, who we call “Creator Sets Free” in our translation. It’s basically the meaning of his name with a little bit of Native spin—instead of “God saves,” “Creator Sets Free.”

You say the words in English the way we think them in our language.

A Native elder, commenting on the First Nations Version

I think what Matthew was trying to get across in the Sermon on the Mount and in the Beatitudes was God’s blessing. In our translation we decided that instead of saying, “Blessed are the poor,” for example, we’d say, “Creator’s blessing rests on the poor.” In other words, this is who God blesses: the poor and the outcast. God blesses our Native people, who have historically been poor and somewhat outcast, even within Christianity. A couple verses later, in Matthew 5:5, the NIV reads, “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.” We translated this as, “Creator’s blessing rests on the ones who walk softly and in a humble manner. The earth, land, and sky will welcome them and always be their home.”

Through the process of rewording these passages, the scripture really started to come alive in a new way, both to myself and to our reviewers. It was so easy to relate to these passages in a way that it hadn’t been previously.

Where did the translation of Mary, “Bitter Tears,” come from?

Mary’s name was a challenge. The Hebrew name can have many different roots. We were drawn to the story in Luke where Mary and Joseph bring Jesus to the Temple and Simon tells her, “A sword will pierce your own soul too” (2:35, NIV). We thought about how Mary is affected by what happens to Jesus. So we went back to the Hebrew root of mara, which means “bitter.” As we continued to research this word’s roots, there was also a sense of salt water connected to the word.

“Bitter Tears” for the mother of Jesus worked out really well. It captures the bitter heartbreak she would feel and how she stands out from every other Bible character as specially chosen.

But then there are so many Marys in the New Testament. We decided to give each one the same basic name but change it a little bit to designate which Mary is being spoken of. Mary Magdalene becomes “Strong Tears,” Mary the sister of Martha becomes “Healing Tears,” etc.

Were there any passages that were especially difficult to translate?

The narrative portions of the New Testament were easier to translate because of the storytelling. When we got into Paul’s theological books, it got a little more difficult. I think both I and the other reviewers had an especially difficult time with 1 and 2 Corinthians. Some of it was Paul’s paragraph-long sentences: He just never stopped. And that’s not how our Native people speak. When we tried to cut down the passages into smaller sentences, there was only so much we could do without getting too redundant.

Even though this is a translation, maybe the first one made by Native people and primarily for Natives, it’s also a gift from Native people to the dominant culture.

There were also some cultural challenges with 1 and 2 Corinthians: women having their heads covered and things like that. We imagined how within our own Native cultures we have different ways of doing things. In the eastern part of the United States, for example, women never sit on the big drum; they stand behind the men. Women in the powwow wear a blanket or something over their shoulders, and it is considered inappropriate for them not to have one while dancing in the circle. So in that passage we put an explanation in italics to give some context to what Paul might have been talking about—maybe it was a cultural practice. It was something that was specific to his particular location: Like one of our Native practices, it wasn’t something that is true for all people in all times and for all tribes.

Who do you hope will use this translation?

I think the book speaks to people in many different ways. Even though this is a translation, maybe the first one made by Native people and primarily for Natives, it’s also a gift from Native people to the dominant culture. I’ve spoken to theologians, Greek scholars, and everyday people who tell me it really speaks to them. I’ve had people who are on all ends of the theological spectrum, from progressive to conservative, tell me that it brings a fresh approach to the scripture.

I was told that two young Native women from the Soboba Indian Reservation in California got an early copy of the book and cried. They said, “Someone really cares about us Native people to do a translation like this.” Just the fact that someone had bothered to do this was so meaningful to them.

We are working on an audio book of the First Nations Version, which will make this content accessible in another way to even more people. We’ve also worked with the Jesus Film Project to create a film based on our translation. It’s an animated version of Matthew 14, of Jesus feeding the 5,000 and Peter walking on the water. We tried to blend Native aspects of the story with its original context, so we’re hoping this version will introduce people to the First Nations Version to help them see Jesus in a different cultural context.

This article also appears in the September 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 9, pages 22-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Aaron Burden

No comments:

Post a Comment