The Second Age (1978 – 1994): A Spider Caught in Its Own Web

In 1978, the Copyright Act B.E. 2521 (A.D. 1978) came into force, with the following provision:

Section 42: Works protected by copyright under the laws of a country which is party to a convention on protection of copyright to which Thailand is also a party, given that the laws of such country also grant copyright protection to works protected by copyright under the laws of other countries party to the same convention, are granted copyright protection under this Act, subject to conditions which may be established through ‘Royal Decree’.

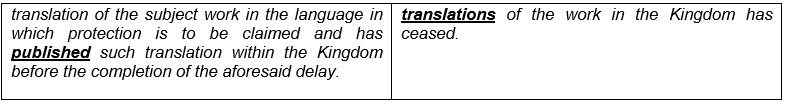

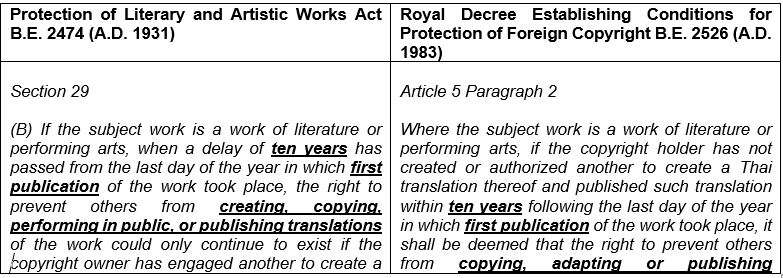

For five years, no Royal Decree was issued, giving the impression that Thai law finally granted identical extent of protection to works of domestic and foreign origins. This impression proved false when the Royal Decree Establishing Conditions for Protection of Foreign Copyright B.E. 2526 (A.D. 1983) was issued, whose Article 5 Paragraph 2 imposed temporal limitations on translation rights of foreign works. Wordings of the previous 1931 Act and the 1983 Royal Decree are compared below:

- Copying the Thai translations of her/his work

- Adapting (including re-translating) the Thai translations of her/his work

- Publishing the Thai translations of her/his work.

The right to create (or authorize the creation of) Thai translations, however, no longer suffered the same temporal limitation. Apart from this small difference, the 1983 Royal Decree’s Art.5 Para.2 is almost identical to the 1931 Act’s s.29(B).

For all we know, the 1983 Royal Decree’s liberation from time limits of the right to create Thai translation of a foreign copyright-protected was not serendipitous. S.29(B) of the 1931 Act aimed at widening the Thai population’s access to international works by cutting short the protection period for translation rights of foreign works to only ten years after publication of the original work, and the 1983 Royal Decree – issued over five decades later to regulate the same issue – should be assessed in light of the same public policy. The 1931 Act allowed Thai publishers to create, reproduce and disseminate masses of Thai translations of foreign works without needing to seek permission from their original authors for over fifty years. During that time, a sufficient body of sensibilities subsisting in foreign literary works had been transposed into the Thai intellectual culture, tuning the nation’s collective thoughts to the international melody – no more copyright-protected foreign works were urgently needed to be translated into Thai. By 1978, the need for modernization no longer justified limiting translation rights in foreign works. Thus, the Thai legislature in 1978 deliberately chose to let the exclusive right to create or authorize Thai translation of a foreign copyright-protected work continue to the full term of the copyright itself.

However, reproduction and distribution of Thai translations made under the exception of the 1931 Act’s s.29(B) is a different issue. By allowing Thai publishers to easily create and exploit Thai translations of foreign copyright-protected works, the 1931 Act’s limitation of translation rights had caused Thai publishers to become economically reliant on the work products made under s.29(B)’s exception. Were they suddenly prevented from publishing and selling the Thai translations created under such exception, collapse of the Thai publishing sector would ensue. Thus, the 1983 Decree, by allowing publishers to continue copying and publishing Thai translations created under the 1931 Act, while barring new translations to be created without the original authors’ permission, was a transitional measure aimed at ensuring survival of the domestic publishing sector while propelling Thailand towards a more complete protection of foreign authors’ translation rights.

So far, so good…

The Thai Supreme Court’s groundbreaking Decision number 3797/2548 (A.D. 2005) involved the Claimant, Agatha Christie Limited, bringing a copyright infringement case against the Defendant, a Thai publisher, alleging that the Defendant had infringed its translation rights by creating, reproducing and selling copies of unauthorized Thai translations of no less than 28 literary works authored by Agatha Christie. The Supreme Court held that the Thai translations of most of these works did not constitute infringement of the Claimant’s translation rights. The reasoning was that the Claimant’s right to prevent others from creating Thai translations of its foreign copyright-protected works had expired since it had not created or authorized Thai translations thereof within ten years following the first publication date of each work, so the unauthorized Thai translations made between 1978 and 1993 (when the 1983 Royal Decree was repealed) did not constitute infringement of the Claimant’s copyright. The Decision shows the Supreme Court assuming that the 1931 Act’s s.29(B) and Art.5 Para.2 of the 1983 Decree were identical in effect and overlooking the small difference between two. Even a superficial interpretation of Art.5 Para.2 would render such assumption untenable.

Had the difference between the 1931 Act’s s.29(B) and the 1983 Decree’s Art.5 Para.2 been discerned, the conclusion should be that all Thai translations created after 1978 of foreign copyright-protected works constituted infringement of the original authors’ translation rights. Surprisingly, the Supreme Court took the opposite view. What’s more? The Court also held that each Thai translation constituted a copyright-protected work of its respective translator because it had been created without infringing the original author’s translation rights! Consequently, the Defendant, (1) having legally obtained copyright from the relevant translators or (2) having no intention to commit a criminal copyright infringement, could freely publish and sell copies of the Thai translations until the copyright term for each one expires.

To this day, a Thai publisher facing allegations of translation right infringement would evoke the “Agatha Christie Decision” to claim that the Thai translation it publishes and sells was created under the exceptions of the1978 Act (supplemented by the 1983 Decree), which gets them instantly off the hook. The Decision has created a seemingly irrefutable norm favoring Thai publishers at the expense of foreign authors – in a manner apparently inconsistent with the legislature’s intent for progress.

In this Episode, we argue that Thailand’s good intentions in updating its laws on translation right protection in 1978 and 1983 have been defeated by judicial interpretation and misunderstood by the publishing sector. The result is cataclysmic for foreign copyright holders. But it gets better, as we discuss the Light at the End of the Tunnel post-1994 in Episode 3.

No comments:

Post a Comment