Book bans are right up there with censorship, the desecration of cultural artifacts and the whitewashing of history, all of which Florida now does routinely in the name of development and white nationalist purity. But I admit: I had a lot of fun reading over at least parts of the list of 1,600 books the Escambia County school system has removed from shelves, supposedly to review and potentially ban.

Librarians review books as a matter of course. They are professionals trained in the art of calibrating the right books to the right school audiences. So there’s nothing wrong with reviewing books along those lines. The problem is that those books have already gone through that process. Most have been on the shelves for years. Many are classics, some are dictionaries–dictionaries–and one of them is the Guinness Book of World Records.

Librarians review books as a matter of course. They are professionals trained in the art of calibrating the right books to the right school audiences. So there’s nothing wrong with reviewing books along those lines. The problem is that those books have already gone through that process. Most have been on the shelves for years. Many are classics, some are dictionaries–dictionaries–and one of them is the Guinness Book of World Records.

I don’t know what could possibly be objectionable in the Guinness book. Maybe the pitchforks of Escambia thought the book encourages children to drink dark beer. Apparently the book does give some attention to animal species, not human unfortunately, that can copulate “more than 50 times in the same three to four hours, all with the same female,” or female chimpanzees copulating with eight different males in 15 minutes. But I’m not sure how that’s sexually explicit. To me it reads more like the set up to one of those brain-twisting math questions on the SAT.

Among the less esoteric rejections, we see titles by Walt Whitman, Sandra Day O’Connor Thurgood Marshall, just about every book by Maya Angelou, even though that famous passage of her getting raped when she was 9, in I Know Why the Cage Bird Sings, is all of two lines, rendered in metaphor: “Then there was the pain. A breaking and entering when even the senses are torn apart.” And that’s it.

Many titles that have been making headlines for the past two years are on an earlier Escambia list that led to a federal lawsuit. But that’s old news. Silencing Ann Frank’s Diary isn’t. Now we’re into not just censorship, but the erasure of people and memories, the erasure of man’s inhumanity toward particular people and races, as is the case with the removal of books by William Faulkner, Alice Walker and Toni Morison.

By the time you find that two books by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the greatest storyteller of the last century, have been removed, it’s no longer surprising that the Encyclopedia of World Costumes is also on the ban list. No doubt, Escambia schools think that children could become gay by spending time looking at frou frous. It’s absurd enough for Ripley’s Believe It or Not, except that that title is banned in Escambia, too.

You can argue that book bans in the age of Amazon, Google and universal libraries are irrelevant. To some extent that’s true. Those of us with means can acquire any book we please, often overnight. But books aren’t cheap, and the days of online bargains are pretty much over. Besides: Americans don’t read much anymore and don’t even know what their children should read. So for a big segment of our school population, school libraries are it. Students either get their books there, or they don’t get them. Their cultural literacy is disproportionately at the mercy of what librarians put on shelves–what librarians are allowed to put on shelves.

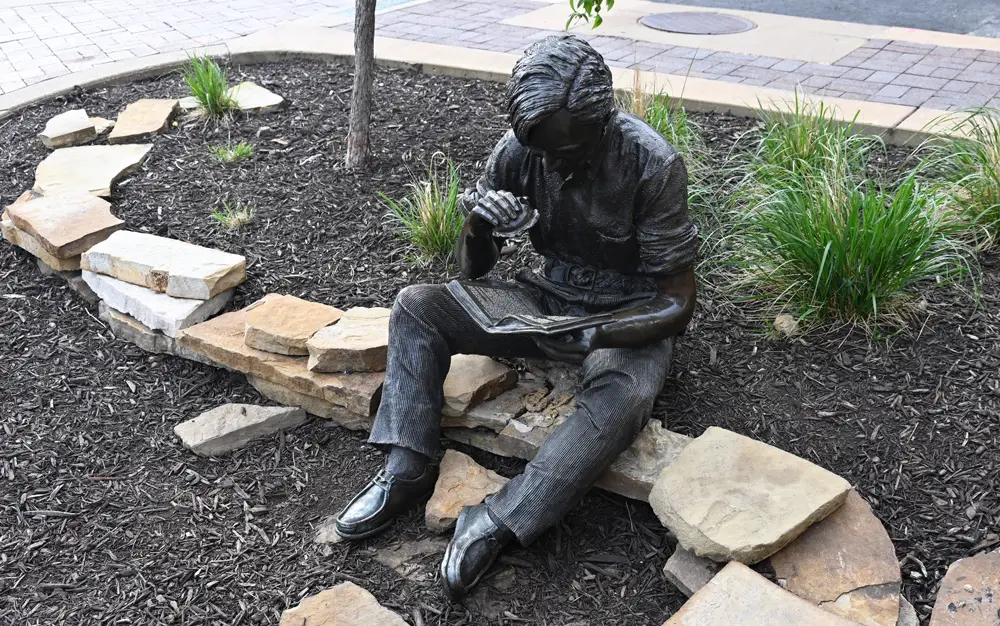

Most reading discoveries are by browsing–the serendipity of finding a great book, discovering a writer who seems to speak to you personally, a story that makes you feel less alone, less of the freak everyone else makes you think you are, more of the human being that you have always been but are afraid to acknowledge. Those are the books that can make a life-changing–a life-affirming–difference in children’s lives. Those are the books that are being removed.

A few people who call themselves parents but are really frustrated bullies who want everyone else to lead the miserable lives they do, at least when they’re not engaging in threesomes, have successfully made black holes of Florida’s school and classroom libraries and further marginalized slews of children whose one solace might have been that one book.

A few people who call themselves parents but are really frustrated bullies who want everyone else to lead the miserable lives they do, at least when they’re not engaging in threesomes, have successfully made black holes of Florida’s school and classroom libraries and further marginalized slews of children whose one solace might have been that one book.

It may not have been any one of the 23 Stephen King books banned, or the Grisham and Crichton and Koontz and maybe even the Picoults books that are literature’s equivalent of that gluey orange sauce McDonalds slathers on its burger imitations. But who are we to say what strikes a chord with a child’s imagination, what speaks to a child’s sense of wonder and self-discovery? Right now in Florida we may no longer ask the question. The bans have it. The rest is irrelevant.

Orange County Public Schools spent $400,000 in tax dollars in overtime pay to media specialists to draw up their own list of nearly 700 titles now found unacceptable (including Milton’s Paradise Lost and the one regained, Saul Bellow’s Herzog, and of course Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, now a metaphor for public schools, but also, thank heavens, Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead: no one will miss her felony-worthy prose). Public money, spent to silence history and deny students literary fun or discovery on the bogus, never-tested assumption that these books harm their readers.

Flagler County went through its own round of deshelving libraries, though it’s done so in more pernicious ways. We don’t really know how many books have been banned because most have been “weeded.” That’s a deceptive term that pretends that removing a book because it’s not read as much or may have been bought by mistake is not book-banning. It is. Teachers and librarians would rather err on the side of caution, otherwise they’d get sued or fired. So you can be certain that whatever happened in Escambia is happening in Flagler and across the state.

And that’s what they call Free Florida.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is the editor of FlaglerLive. A version of this piece airs on WNZF.

No comments:

Post a Comment