[unable to retrieve full-text content]

The First 10 Words of the African American English Dictionary Are In The Philadelphia TribuneMonday, May 29, 2023

Sunday, May 28, 2023

Barcelona loanee hits out at media for ‘incorrect translation’: “Call me if you need help” - Barca Universal - Translation

Barcelona defender Samuel Umtiti has hit out at media outlets after an incorrect translation of his interview, which many translated as he felt ‘imprisoned at Barça for four years’.

“To all journalists and newspapers… If you need help translating, you can call me next time. Depression equals depression, nothing to do with “prison” or jail. Thank you very much,” wrote the defender on his Instagram account (h/t Mundo Deportivo).

The exit-bound Barcelona defender recently spoke with Canal+ where he talked about his frustration at Barcelona, saying that the last four years were very difficult for him.

“I’m fine. I’ve spent four years in the Galleys, they’ve been hard four years, but now I’ve rediscovered my smile and the joy of playing football. They have given me this confidence here and I’ve been able to express myself as I did years ago,” said the defender.

“I don’t know if it was depression, but it was really complicated and difficult at all levels. I closed myself off a lot with my close people.”

“There were times in Barcelona when I didn’t want to leave the house. My friends told me to go out to change my mind, but I told them no, that I wanted to be alone. It was very complicated,” said the defender, who in no way described his Barcelona tenure as a prison.

Umtiti moved to Serie A outfit Lecce on loan at the beginning of the ongoing season. Ever since moving to Italy, the French defender has found a new life and is one of their top performers of the season.

As a result, the Serie A team is now exploring the possibility of signing the defender on a permanent transfer while there are other reports that he wants to move back to Olympique Lyon.

In any way, it is certain that Umtiti has no place in the current Barcelona team and despite his emotional comeback from mental trauma, he will be sold in the summer.

AI4Bharat: Putting India on the global map of cutting-edge AI innovation - Economic Times - Translation

When Microsoft chief Satya Nadella visited India in January this year, a unique app caught his attention.Jugalbandi, a chatbot which leverages language models from ‘AI4Bharat’ along with reasoning models from Microsoft’s Azure OpenAI can be used to get information on 170 government schemes in local languages. The chatbot, which combines speech recognition, translation, text-to-speech, and large language models, has been created to allow people

African American English Dictionary gives first look at 10 words - New York Daily News - Dictionary

Unfortunately, our website is currently unavailable in your country. We are engaged on the issue and committed to looking at options that support our full range of digital offerings to your market. We continue to identify technical compliance solutions that will provide all readers with our award-winning journalism.

Oshi No Ko Opening's Artist Releases Official English Cover & Translation - Screen Rant - Translation

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Oshi No Ko Opening's Artist Releases Official English Cover & Translation Screen RantSaturday, May 27, 2023

Burnsville native who dreams in Bulgarian wins share of International Booker Prize - Star Tribune - Translation

When Angela Rodel studied linguistics at Yale University, she didn't know translating was a legitimate career. On Tuesday, she shared the prestigious International Booker Prize for translating "Time Shelter," by Georgi Gospodinov, from Bulgarian into English.

"We've had eight hours of interviews today. It's insane! But I'm not complaining," Rodel said by phone from London, where the Booker ceremony took place. She and Gospodinov share the roughly $62,000 prize for the best work in translation published in the United Kingdom.

The 1992 graduate of Burnsville High School studied Russian and German at Yale, partly because, "I was a dark, angsty teenager." But she had sparked to Russian in high school: "This was totally strange but I guess the winds of perestroika made it there because one of the French teachers started teaching Russian, too."

At Yale, Rodel joined a Slavic chorus after hearing the music and thinking, "I want my voice to sound like that."

She went to Bulgaria as a Fulbright scholar after Yale, then earned a master's degree in linguistics from UCLA. On a return visit to Bulgaria in 2004, "I decided to stay. My husband at the time was a musician and poet and Sofia is a really small town. We all knew each other, so I met all these writers. Someone would give me a poem or story and I would translate it, just for fun."

Almost by accident, she became a full-time translator, which she now balances with being executive director of the Bulgarian Fulbright Commission.

Rodel hopes the Booker recognition helps change the notion that translated works are "second-hand goods."

"There's a perception that it's somehow 'less than' because it wasn't originally in English. But there are brilliant, talented writers all over the world," said Rodel, who speaks Bulgarian at home with husband Viktor and daughter Kerana and often dreams in the language.

Her job is not line-by-line transcription but something more artful.

"You want the reader to have a similar emotional experience in the translation as they would in the original. You try to capture the atmosphere, the style of the work. So, if there's something experimental, there should be something experimental in the translation," Rodel said. "If there's a humorous novel, with plays on words, maybe you can't do the exact same pun in a given sentence but there may be an opportunity to do one a few sentences later that works in English."

The Bulgarian language presents challenges for an English translator, including different verb tenses and gendered nouns.

The Burnsville native has worked often with Gospodinov, who also lives in Sofia. When the two learned in March that "Time Shelter" made the 13-book longlist, she said, "We thought, 'This is amazing. A Bulgarian book has never even made the longlist, so this will be the end of that.'"

They won the whole thing at a ceremony that included actor Toby Stephens reading from "Time Shelter."

"The invitation said to 'dress smart,'" said Rodel, who nodded to the art of translation by pairing a cocktail dress with a Bulgarian folk-art necklace. "It all started at 6 but they didn't announce the award until 10, so we were all just dying."

Rodel is working on several projects, including a translation of a Bulgarian novel to be published in January. Meanwhile, she and daughter Kerana will visit Eagan in July for a family reunion and lots of time in Minnesota parks.

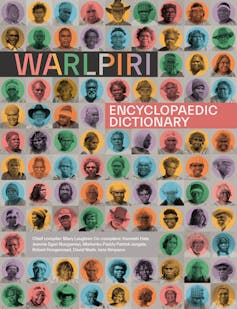

Six decades, 210 Warlpiri speakers and 11,000 words: how a groundbreaking First Nations dictionary was made - The Conversation - Dictionary

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people. The symbol † next to a personal name is a conventional respectful indicator that the person has died.

The first large dictionary of the Warlpiri language began in 1959 in Alice Springs, when Yuendumu man †Kenny Wayne Jungarrayi and others started teaching their language to a young American linguist, †Ken Hale.

Sixty years in the making, the Warlpiri Dictionary has been shortlisted for the 2023 Australian Book Industry Awards – a rarity for a dictionary.

Spoken in and around the Tanami Desert, Warlpiri is an Australian Aboriginal language used by around 3,000 adults and children as their everyday language.

Warlpiri artist Otto Sims Jungarrayi says:

In the old days when kardiya [non-Indigenous] people came, when they reached this continent, we had jukurrpa “law” here, not written on paper but true jukurrpa “law”, that the ancestors gave us. Now we put our language and our jukurrpa law on paper.

The dictionary and these materials represent the authority of elders, even if those elders are no longer present.

From the start of this project, Hale tape-recorded and transcribed many hours of Warlpiri people talking about language, country, kin and diverse aspects of traditional life.

The Warlpiri people he recorded came from different parts of Warlpiri country, speaking their own distinctive varieties of the language. From this material, Hale hand-wrote the words and meanings on small slips of paper that could be sorted in different ways.

Read more: Friday essay: my belly is angry, my throat is in love — how body parts express emotions in Indigenous languages

Making a dictionary

Bilingual education was introduced in Northern Territory schools in the 1970s. It meant the Warlpiri communities needed a common spelling system.

In the early 1970s, at Lajamanu community, Warlpiri men †Maurice Luther Jupurrurla and †Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala worked with linguist †Lothar Jagst to develop that spelling system. It was adopted in the new bilingual schools.

Dictionary work became a focus for the new linguist position at Yuendumu School, first filled in 1975 by the dictionary’s chief compiler, Mary Laughren. She worked closely in the school with dictionary co-compiler †Jeannie Egan Nungarrayi.

Over the next four decades, in a type of early crowd-sourcing, more than 210 Warlpiri speakers from different Warlpiri communities worked on and off with Laughren and others. They found words (ultimately 11,000 plus), decided how to spell them, translated them into English, showed how they can be used in Warlpiri sentences, and provided the social, cultural and biological information that makes this a truly encyclopaedic dictionary.

Co-compiler †Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala took on a mission to preserve the meanings of conceptually difficult and older words by writing definitions directly in Warlpiri. The 4,000 complex definitions in Warlpiri provide Warlpiri perspectives on the most important characteristics of each concept.

For example, in these two entries, both defined by †Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala:

Kukuju-mardarni is like when a person is happy or is sitting on their own feeling satisfied, or is nodding off to sleep, or is smiling – a man or a woman feeling happy about something like a lover or about their spouse whom they desire or because their lover has sent them a message.

Kukuju-mardarni, ngulaji yangkakujaka yapa wardinyi manu yangka nyinami kurntakurntakarra manu yukukiri wantinja-karra manu yinkakarra karnta manu wati yangka wardinyi nyiya-rlanguku marda waninja-warnuku manu marda kali-nyanuku kujaka yangka wardu-pinyi manu marda yangka kujakarla jaru yilyamirni waninja-warnurlu.

And:

Jalangu is a day which is not tomorrow or not yesterday. It is today. It is the time of daylight that is now.

Jalangu, ngulaji yangka parra jukurra-wangu manu pirrarni-wangu, jalanguju. Yangka parra rdili kujaka karrimi jalanguju.

Then, there was the laborious task of checking the draft dictionary entries.

Computer scientists assisted with data management and experimented with an electronic display, called Kirrkirr. Kirrkirr users can type in a word and see a visual display of meanings connected to that word (for example, words with a similar meaning, or the opposite meaning). They can also hear it pronounced, and see examples of how the word is used in Warlpiri.

Experts (among them anthropologists, Bible translators, botanists and zoologists) helped to identify plants, animals and more.

And artists, including Jenny Taylor and Jenny Green, provided images they had created for the Institute for Aboriginal Development Press Picture Dictionary series and other publications.

Passing on Warlpiri language

Warlpiri people have been working to pass on their language, to ensure their children and grandchildren can speak it.

Tess Ross Napaljarri began working as a teaching assistant 50 years ago, setting up the Yuendumu bilingual education program. She has described how she learned to read and write Warlpiri. “We became partners with the teachers in how to teach the Warlpiri children,” she says.

The children were learning their first language, Warlpiri, and second language, English, “and they were really smart on both languages”. The commitment of Warlpiri people to bilingual education has been – and continues to be – enormous. Since 2005, they have dedicated royalty money through the Warlpiri Education and Training Trust into supporting this work.

Warlpiri want Warlpiri children to be able to speak for themselves in a meaningful way – in both English and Warlpiri. Today, many Warlpiri now live away from Warlpiri country.

Tess’s niece, Bess Price Nungarrayi, is now assistant principal at Yipirinya School, on Arrernte country in Alice Springs. With more limited opportunities for hearing Warlpiri, Bess says the dictionary will be very useful in strengthening children’s Warlpiri.

This bilingual dictionary has many audiences. Warlpiri people enriching their knowledge of their language, Warlpiri and non-Warlpiri teachers preparing learning materials, Ranger groups studying eco-systems on Warlpiri country. And anyone wanting to learn about Warlpiri language, history, natural history knowledge and culture.

It can help Warlpiri speakers translate complex Warlpiri words into English, and it’s also an important tool for outsiders to learn Warlpiri – something Warlpiri people have long encouraged.

Read more: Friday essay: we are the voice – why we need more Indigenous editors

Future generations

Ormay Gallagher Nangala, a Warlpiri educator at the Bilingual Resources Development Unit, says:

Junga jintajinta-manulu nyurruwarnu-patu-wiyi ngulalpalu nyinaja, purlkapurlka wurlkumanu. And ngulajangkaju-ngalpa manurra, young people ka wangka school-rla karnalu warrki-jarri ngulalku, ngulangkalu jintajinta-manu and jungarlupa ngurrju-manu nyampu naa dictionary. Kurdu-kurdurlulu ngula nyanyi yangka.

The dictionary makers brought together information and intentions from the elders who have now passed away, the people who have been working in education for many years, and the future generations who will continue to learn Warlpiri.

This article was written with the collaboration of senior Warlpiri women Ormay Gallagher Nangala and Tess Ross Napaljarri.