Michael Dirda

THE WASHINGTON POST – What do you do when a book – a classic, no less, and one beloved by millions of readers – proves disappointing?

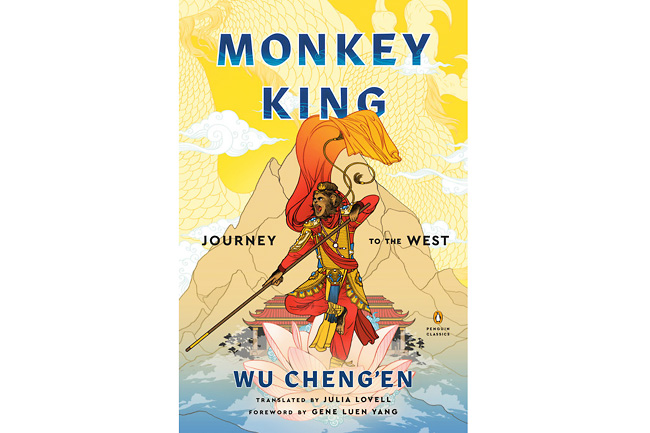

I had expected to love Monkey King the new translation and abridgment by Julia Lovell of the episodic 16th-century Chinese novel, Hsi-yu chi also known as Journey to the West. The book was first published anonymously, and its authorship is consequently uncertain, though usually attributed to a minor poet and littérateur named Wu Cheng’en.

Today, Journey to the West is said to be the most popular book in East Asia, as well as a seed-text for children’s stories, films, anime and comics.

Appropriately, then, Lovell’s translation carries a foreword by Gene Luen Yang, MacArthur-Award-winning author of the graphic novel American Born Chinese which draws on this rumbustious fantasy.

The marvel-filled narrative – 100 chapters in the original – derives from popular tales and dramas about a shape-changing trickster and proto-superhero who happens to be a talking monkey. Its other characters, as Lovell – professor of Chinese at the University of London – notes in her excellent introduction, include “deities, demons, emperors, bureaucrats, monks, animals, woodcutters, bandits and farmers” – in short a cross-section of Ming-era imperial China.

The opening chapters depict the mysterious birth of Monkey, his early religious training under a Taoist Immortal, his acquisition of a supernatural fighting staff, and the trouble this simian upstart causes when, in his quest for the secret to eternal life, he disrupts the celestial court-in-the-clouds of the Jade Emperor. There he offends virtually everyone, devouring the Jade Empress’s life-extending peaches and drinking the immortality elixirs of Laozi, the Taoist patriarch.

Exiled back to Earth, Monkey and his armies battle the celestial forces successfully until the Buddha finally imprisons him under a mountain. His adventures, however, are just beginning.

All these initial chapters of Monkey King” exhibit a rollicking exuberance, somewhat like Rabelais’s hyperbolic accounts of the giants Gargantua and Pantagruel. Monkey consistently acts with crude outrageousness – at one point he actually urinates on the Buddha’s hand.

Because the novel’s Chinese vernacular is both vulgar and linguistically playful, Lovell’s translation adopts a snappy contemporary vibe. Heaven, we learn, “runs a

cashless economy”.

The welcome sign outside the Underworld reads, “The Capital of Darkness: A Fine City”. A hermit, asked how he’s doing, answers, “Oh, same old, same old.” Some of Lovell’s descriptive epithets even recall the comic sententiousness of Ernest Bramah’s tall tales about the resourceful Kai Lung.

The Pillar of Ultimate Peace, for instance, refers to the execution block.

I wanted to like the book more. Even abridged to a quarter of the original, its long central section struck me as repetitive, tedious and cartoonishly crude.

Overall, Monkey King lacked the charm of Western fairy tales, medieval chivalric romances or The Arabian Nights, each of which it occasionally resembles. Neither was there any of the wondrous eeriness or poignancy of Pu Songling’s slightly later classic, Strange Stories From a Chinese Studio.

No comments:

Post a Comment