Every season I pour over the catalogs and galleys of new releases in translation and highlight some of the titles that I’m excited about for Book Riot. I was especially impressed with this spring and summer’s incredible offerings of literature translated from Korean. There were even more stunning titles than usual and much more than I could fit into my original list, where I try to highlight a wide diversity of languages and countries. So I was inspired to create a list solely of the titles translated from Korean this season as an added bonus. And because I couldn’t help myself, I also looked ahead at and included some exciting early fall titles.

Looking at this list, I’m overwhelmed by the overall quality of all of these titles — to put it simply, every single one of them is a banger. I’ve always loved Korean literature in translation, but to have more titles available than ever before, written and translated at this high standard, feels like an absolute gift. I’m also impressed by the variety of what’s currently being translated from Korean right now. There are critically acclaimed and beloved authors and translators returning with their newest book, like my most-anticipated book of the season: Phantom Pain Wings by Kim Hyesoon and translated by Don Mee Choi, alongside exceptional English-language debuts like Walking Practice by Dolki Min and translated by Victoria Caudle and Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan and translated by Chi-Young Kim. There’s also a fascinating mixture of form and genre, from science fiction to literary fiction and novels, short stories, and poetry alike. It’s a thrilling time to be a lover of Korean literature in translation!

Best New Korean Literature in Translation

Walking Practice by Dolki Min, translated by Victoria Caudle

Walking Practice was my biggest surprise of the season! The novel follows a shapeshifting alien that is the lone survivor of their planet’s destruction, now confined to Earth’s atmosphere. To survive, they learn to use dating apps and their shapeshifting abilities to seduce and eat their suitors. The alien’s inner commentary — horrifying and strange and yet also thoughtful and endearing — about what it means to be an outsider, acting as “human,” and their desire to belong is utterly fascinating and a biting critique of social structures that discriminate against queer, gender-nonconforming, and disabled people. Victoria Caudle’s translation was striking, both insightful and utterly original, and I was grateful for her translator’s note that provided a glimpse behind the curtain. Blending humor and horror, science fiction and searing cultural commentary, Walking Practice stuns — almost as if I was its next victim. (HarperVia, March 14)

I Went to See My Father by Kyung-Sook Shin, translated by Anton Hur

I Went to See My Father follows the life of a woman reconnecting with her elderly father after the death of her own daughter. While taking care of him, she finds a chest of letters and begins to piece together stories of a life she never knew. It is a powerful and haunting novel about family, war, loss, and fatherhood. While Kyung-Sook Shin is widely known internationally for the international bestseller and winner of the Man Asian Literary Prize Please Look After Mom, translated by Chi-Young Kim, I also recommend The Girl Who Wrote Loneliness, translated by Ha-yun Jung, a haunting coming-of-age story set against the backdrop of Korea’s industrial sweatshops of the 1970s, and The Court Dancer, translated by Anton Hur, a beautifully written historical novel set during the dramatic final years of the Joseon Dynasty. (Astra House, April 11)

Greek Lessons by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith and Emily Yae Won

I love Han Kang’s sharp and stunning novels, including the Man Booker International Prize winner The Vegetarian, Human Acts, and The White Book, all translated by Deborah Smith, and was eagerly anticipating this new book. Of her past novels, Greek Lessons, translated by Smith and Emily Yae Won, seems to most closely resemble The White Book — a novel that uses an exploration of the color white to think about grief and loss. Likewise, Greek Lessons is a meditation on human connection told through the act of learning and sharing language, specifically Ancient Greek. It’s a pleasure to watch Kang think in this radiant translation. (Hogarth, April 18)

Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan, translated by Chi-Young Kim

Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize, Whale is the English-language debut of Cheon Myeong-kwan, an award-winning South Korean novelist and screenwriter, and translated by Chi-Young Kim, who received the Man Asian Literary Prize for her translation of Please Look After Mom by Kyung-Sook Shin. It is a multigenerational story of three women set in a remote, coastal village in the rapidly modernizing South Korea of the latter half of the 20th century. Whale is widely considered a modern classic in South Korea and has been compared frequently to One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez with its mix of magical and realist elements and its epic scale, but Whale is its own creature entirely — a strange and beguiling blend of satire, folklore, Korean Han, and something else that feels indescribable. (Archipelago, May 2)

Phantom Pain Wings by Kim Hyesoon, translated by Don Mee Choi

When I first wrote about Autobiography of Death by Kim Hyesoon and translated by Don Mee Choi, I said that it felt like one of the most important books I’ve ever read. I still feel that way, and my estimation of this author and translator continues to grow with this new collection that also grapples with death, memory, and trauma but is even more deeply personal. Kim Hyesoon writes, “I came to write Phantom Pain Wings after Daddy passed away. I called out for birds endlessly. I wanted to become a translator of bird language.” Like its predecessor, one of the best parts of this collection is watching Hyesoon and Don Mee Choi’s fiercely intelligent minds at work, and I’m grateful for the inclusion of Hyesoon’s profound essay “Bird Rider” and Don Mee Choi’s translator’s diary. (New Directions, May 2)

Counterweight by Djuna, translated by Anton Hur

Djuna is a novelist and film critic, widely considered to be one of South Korea’s most important science fiction writers. They have also published their books anonymously for more than 20 years. This is their first novel to be translated into English — and they couldn’t be in better hands than with acclaimed translator Anton Hur — and when I heard that Djuna had conceived of this work as a “low-budget science fiction film” I was immediately intrigued. Within the first few pages, I knew I was already deeply enmeshed in something special. This novel is dizzying and cinematic with corporate politics, family dynamics, an elevator into space, neuro-implant “worms,” an island nation’s fight against a colonial/capitalist takeover, and so much more. (Pantheon, July 11)

At Night He Lifts Weights: Stories by Kang Young-sook, translated by Janet Hong

Kang Young-sook is an award-winning author of many novels and short story collections and currently teaches creative writing at Korea National University of Arts. This short story collection is her first to be translated into English, by none other than the brilliant Janet Hong. I’m a great admirer of Hong’s translations of the short stories of Ha Seong-Nan and numerous graphic novels by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim, Yeong-Shin Ma, and Ancco, among others. Perceptive and subversive, the stories in At Night He Lifts Weights vary in tone and genre, but each is singularly captivating, swirling around themes of loss — ecological destruction, loneliness, and death. Each has a subtle illusion of calm that conceals what lies below in the unnerving depths. (Transit Books, September 12)

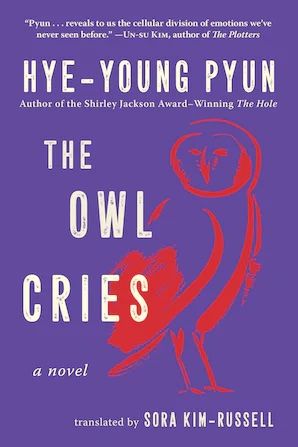

The Owl Cries by Hye-young Pyun, translated by Sora Kim-Russell

In this intense, psychological thriller, park ranger In-su Park decides to search for a missing man in the woods after a series of bizarre incidents, including discovering a mysterious note left on his desk that says, “The owl lives in the forest.” Just like in their Shirley Jackson Award–winning The Hole, Hye-Young Pyun and translator Sora Kim-Russell create a fast-paced and all-consuming story with an unusual narrator. In-su Park searches desperately for the missing man while also discovering more than he’d like in the forest, the people around him, and in himself. A novel of secrets, isolation, and pain, The Owl Cries is another tightly executed feat of writing. (Arcade, October 3)

Looking for even more great recommendations of literature in translation from this season? Check out 10 of the Best New Books In Translation Out Spring 2023.