[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Rotary Club of Jamestown Donates Translation Earbuds to JPS Chautauqua TodaySunday, April 24, 2022

Saturday, April 23, 2022

Man Charged With Threatening Merriam-Webster Over Gender Definitions - The New York Times - Dictionary

The man, Jeremy David Hanson, 34, threatened in October to shoot and bomb the company’s offices because of its definitions of “girl,” “boy,” “trans woman” and other words, federal authorities said.

A California man was arrested this week on charges that he sent messages to Merriam-Webster in which he threatened to shoot and bomb its offices because he didn’t like the company’s dictionary definitions relating to gender identity, the authorities said.

The man, Jeremy David Hanson of Rossmoor, Calif., who was arrested in California on Tuesday, threatened to kill every employee of the Massachusetts-based company, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts said in a statement on Friday.

He was charged with one count of interstate communication of threats to commit violence and released on conditions in California, the statement said. He is set to appear in U.S. District Court in Massachusetts on April 29.

From Oct. 2 to Oct. 8, 2021, Mr. Hanson, 34, sent anonymous comments and messages to Merriam-Webster, which publishes a widely used online dictionary, condemning the company for changing the definitions of words including “boy, “girl” and “trans woman,” according to an affidavit filed by an F.B.I. agent this month.

“There is no such thing as ‘gender identity,’” he wrote in a comment about the definition of “female.” “The imbecile who wrote this entry should be hunted down and shot.”

One of Merriam-Webster’s definitions of female is “having a gender identity that is the opposite of male.”

Mr. Hanson escalated his threats from there, sending messages saying that the company’s headquarters should be “shot up and bombed,” the statement said. He wrote that, by changing certain gender-based definitions, the company was taking part in efforts to “degrade the English language and deny reality.”

In October, Merriam-Webster reported the threats to the F.B.I., which tracked Mr. Hanson through his I.P. address, the bureau’s affidavit said. Because of the threats, the company closed its offices in Springfield, Mass., and New York for five days, prosecutors said.

It was not clear if Mr. Hanson had a lawyer. Messages left at a phone number listed under his name on Friday night were not immediately returned.

His mother told investigators that her son had autism and was “fixated on transgender issues,” the affidavit said.

In recent years, Merriam-Webster, the country’s oldest dictionary publisher, has updated certain definitions to be more inclusive of shifting attitudes around gender.

Representatives for the company did not immediately return emails or phone calls seeking comment on Friday night.

“Hate-filled threats and intimidations have no place in our society,” Rachael S. Rollins, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts, said in the statement.

Prosecutors said that while they were investigating Mr. Hanson’s messages, they found threats that they believed he had made to the American Civil Liberties Union, Hasbro, Land O’Lakes, a New York rabbi and others. He repeatedly used the word “Marxist,” they said.

In the statement from the U.S. attorney’s office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta, the special agent in charge of the F.B.I.’s Boston division, said that Mr. Hanson’s threats “crossed a line.”

“Everyone has a right to express their opinion,’’ Mr. Bonavolonta said. “but repeatedly threatening to kill people, as has been alleged, takes it to a new level.”

Friday, April 22, 2022

Jhumpa Lahiri’s Identity Swings in ‘Translating Myself and Others’ - The Wall Street Journal - Translation

Lahiri, photographed in Princeton, New Jersey, by Heather Sten.

“A translation dilemma is among my earliest memories,” Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest book begins, as she recalls a kindergarten teacher insisting she and her classmates write Mom on a Mother’s Day card, when Lahiri called her mother by the Bengali term Ma. In Translating Myself and Others, out May 17 from Princeton University Press, she collects recent essays on the process of translation, writing in Italian for the past decade and her new identity living between languages. Many essays in the book were written in English, a few translated from Italian and one originally composed in a hybrid of both.

Lahiri was born in London to Indian parents who settled in Rhode Island when she was 3. She won the Pulitzer Prize for her first book, the 1999 story collection Interpreter of Maladies—her obsession with translation right there in the title—which, like her bestselling novels The Namesake and The Lowland, depicts Indian-Americans caught between two cultures.

In 2012, she moved with her husband, the journalist Alberto Vourvoulias-Bush, and their two children to Rome, where she’s since published four books in Italian (and edited a collection of Italian stories) with more on the way, including In Other Words (2016), a meditation on learning to write in a new language, translated by Ann Goldstein, and Whereabouts (2018), a poetic, elliptical novel about a woman meandering through her unnamed Italian city that Lahiri translated into English herself. Lahiri has also recently translated three novels by the Italian writer Domenico Starnone.

She now teaches creative writing and translation at Princeton, making frequent trips to Rome. In July, she will join Barnard as a professor of English and director of creative writing. A book of poetry, Il quaderno di Nerina (Nerina’s Notebook), was published in Italy in 2021, and her collection Racconti romani (Roman Stories) is set to be published there this fall. Her U.S. publisher, Knopf, plans to bring both books out in English, with a timeline to be determined.

To the inevitable question—is she writing any fiction in English now?—Lahiri has a quick, contented answer: “No.”

This new book seems like a declaration that you are now a translator as much as a fiction writer, and that translation is its own artistic form. Do you see it that way?

I do see it that way. I felt the need to reiterate this more complex and more accurate definition of what translation is. My identity as a writer has come to its fullest form now that I am also an active translator, and I’m thinking so much about translation alongside my own writing. The line between the two is very malleable. I find that very stimulating to think about, to recognize how much of translation is writing and to recognize, conversely, how much of writing is a form of translation.

What language do you think and dream in now?

It depends on what the dream is, what the thought is. If you have more than one language, you are living, thinking, dreaming, in my case writing and reading in more than one language. I have Bengali thoughts in my head, I have English thoughts in my head, and I have Italian thoughts in my head. There’s no one language, because I don’t come from any one language. Technically I was brought up with Bengali, but because English entered in so early and then played such a heavy role in my formation as a person, as a reader and a writer and student, in my conscious memory I can’t remember any kind of monolingual universe.

In your new book, you refer to what you called an “anguished decision” to come back to live in the U.S. after you’d been living in Rome for a few years. Why was that so anguished?

It was anguishing because I didn’t want to leave Rome, where I feel happiest. I wanted to remain in that place where I feel the most fulfilled and the most inspired I’ve ever felt in my life. It’s like a relationship, right? You want to be with the people you love. In my case, I wanted to be in the place I love. But I did come back because there was an opportunity to teach at Princeton, and I was curious enough about what that might be like.

The main thing it has enabled me to do is to produce essentially all of the books I’ve written in the past decade, because the financial stability I have now from a teaching job enabled me to take greater risks in my writing. All of the essays I wrote, many of them for this translation book, I just wrote because I wanted to write them. Some were commissioned for no money. It’s given me enormous freedom to write in Italian. There were different kinds of expectations, shall we say, placed on my English language production, different kinds of print runs, different kinds of book tours, different kinds of audiences.

You’ve said that when you started writing in Italian, some people thought you were throwing your career away. Where did that reaction come from?

It came from all over the place, more in the Anglosphere, less in Italy. People in audiences, at events, people who came up to get their book signed, who were disappointed and saying, “Aren’t you ever going to write in English anymore? What happened? I used to like you.” But it was important for me to remind myself that my writing has never been a career in my head. Not to be naive. You write a book and you get this big advance and you sell all these copies, and there is an economic reality. I experienced that economic reality and have been very grateful for it. But I also feel like I’m in a different position right now, so that I can say yes, I want to take on this translation project that’s going to take me the next six years, that couldn’t possibly amount to a living wage.

You dedicate this book to your mother and write very eloquently about how translating Ovid’s Metamorphoses while she was dying was a kind of consolation. How so?

Ovid is describing a state of transformation again and again and again, shifting from that character to this person, to that deity to that animal. That was the thing that enabled me to translate, if you will, what was happening to her body as a metamorphosis. In some sense, death is a metamorphosis from living to dying, your body literally alters to a state in which it is no longer functioning. It was the fact that I was so deeply immersed inside of a poem that was so attentive to that, to that reality of what happens when we die. I found that really revelatory and difficult to take in, but I had to take it in because it was happening in real life.

Here, in her own words, a few of Lahiri’s favorite things.

“The glass-top table was given to me by my friend the poet Alberto de Lacerda. He taught me at Boston University in graduate school. It has been beside my reading chair since 1997. On the table is a copy of Oliver Twist I bought in the bookshop in the home of Charles Dickens when I was 12 years old. It was the first time I set foot in an author’s home. It was so thrilling. On top of the book is a list. When I was in college, I took a Shakespeare course with Edward Tayler. He wrote down these six points, kind of a road map to how to write; it felt like he was an oracle. The jar with shells and rocks in it is a sampling of the things I pick up on the beach when I’m in Wellfleet [Massachusetts]. I can’t really be at peace if I don’t have a piece of the sea in my house. Behind it in a box frame is a Roman postcard of a young woman playing a double pipe that I discovered and grew attached to long before I ever went to Rome. It’s very powerful to be drawn to something that you don’t realize comes from a place that’s going to call to you and become another home. In front of that is a statue of Saraswati, the goddess of learning, given to me by an aunt of my mother’s in Kolkata who was a Sanskrit professor. She gave it to me as a kind of talisman for my studies, and I’ve kept it by my desk since my college years. In the large frame is a watercolor by my grandfather. I believe this was from his imagination, not from being in Kashmir, which is the landscape. The marbled-paper box on the table is the first object from Italy I ever possessed. I keep my pen cartridges inside of it. The perfume bottle on top of the box belonged to my mother. She died a year ago. She was not a very vain person, but she loved fine perfumes. She used the stopper to apply vermillion to her hair, which is the traditional symbol of a Bengali married woman. If you look carefully, you can see the stain of the vermillion powder that she would apply to her hair parting around the base of the stopper.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s Identity Swings in ‘Translating Myself and Others’ - The Wall Street Journal - Translation

Lahiri, photographed in Princeton, New Jersey, by Heather Sten.

“A translation dilemma is among my earliest memories,” Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest book begins, as she recalls a kindergarten teacher insisting she and her classmates write Mom on a Mother’s Day card, when Lahiri called her mother by the Bengali term Ma. In Translating Myself and Others, out May 17 from Princeton University Press, she collects recent essays on the process of translation, writing in Italian for the past decade and her new identity living between languages. Many essays in the book were written in English, a few translated from Italian and one originally composed in a hybrid of both.

Lahiri was born in London to Indian parents who settled in Rhode Island when she was 3. She won the Pulitzer Prize for her first book, the 1999 story collection Interpreter of Maladies—her obsession with translation right there in the title—which, like her bestselling novels The Namesake and The Lowland, depicts Indian-Americans caught between two cultures.

In 2012, she moved with her husband, the journalist Alberto Vourvoulias-Bush, and their two children to Rome, where she’s since published four books in Italian (and edited a collection of Italian stories) with more on the way, including In Other Words (2016), a meditation on learning to write in a new language, translated by Ann Goldstein, and Whereabouts (2018), a poetic, elliptical novel about a woman meandering through her unnamed Italian city that Lahiri translated into English herself. Lahiri has also recently translated three novels by the Italian writer Domenico Starnone.

She now teaches creative writing and translation at Princeton, making frequent trips to Rome. In July, she will join Barnard as a professor of English and director of creative writing. A book of poetry, Il quaderno di Nerina (Nerina’s Notebook), was published in Italy in 2021, and her collection Racconti romani (Roman Stories) is set to be published there this fall. Her U.S. publisher, Knopf, plans to bring both books out in English, with a timeline to be determined.

To the inevitable question—is she writing any fiction in English now?—Lahiri has a quick, contented answer: “No.”

This new book seems like a declaration that you are now a translator as much as a fiction writer, and that translation is its own artistic form. Do you see it that way?

I do see it that way. I felt the need to reiterate this more complex and more accurate definition of what translation is. My identity as a writer has come to its fullest form now that I am also an active translator, and I’m thinking so much about translation alongside my own writing. The line between the two is very malleable. I find that very stimulating to think about, to recognize how much of translation is writing and to recognize, conversely, how much of writing is a form of translation.

What language do you think and dream in now?

It depends on what the dream is, what the thought is. If you have more than one language, you are living, thinking, dreaming, in my case writing and reading in more than one language. I have Bengali thoughts in my head, I have English thoughts in my head, and I have Italian thoughts in my head. There’s no one language, because I don’t come from any one language. Technically I was brought up with Bengali, but because English entered in so early and then played such a heavy role in my formation as a person, as a reader and a writer and student, in my conscious memory I can’t remember any kind of monolingual universe.

In your new book, you refer to what you called an “anguished decision” to come back to live in the U.S. after you’d been living in Rome for a few years. Why was that so anguished?

It was anguishing because I didn’t want to leave Rome, where I feel happiest. I wanted to remain in that place where I feel the most fulfilled and the most inspired I’ve ever felt in my life. It’s like a relationship, right? You want to be with the people you love. In my case, I wanted to be in the place I love. But I did come back because there was an opportunity to teach at Princeton, and I was curious enough about what that might be like.

The main thing it has enabled me to do is to produce essentially all of the books I’ve written in the past decade, because the financial stability I have now from a teaching job enabled me to take greater risks in my writing. All of the essays I wrote, many of them for this translation book, I just wrote because I wanted to write them. Some were commissioned for no money. It’s given me enormous freedom to write in Italian. There were different kinds of expectations, shall we say, placed on my English language production, different kinds of print runs, different kinds of book tours, different kinds of audiences.

You’ve said that when you started writing in Italian, some people thought you were throwing your career away. Where did that reaction come from?

It came from all over the place, more in the Anglosphere, less in Italy. People in audiences, at events, people who came up to get their book signed, who were disappointed and saying, “Aren’t you ever going to write in English anymore? What happened? I used to like you.” But it was important for me to remind myself that my writing has never been a career in my head. Not to be naive. You write a book and you get this big advance and you sell all these copies, and there is an economic reality. I experienced that economic reality and have been very grateful for it. But I also feel like I’m in a different position right now, so that I can say yes, I want to take on this translation project that’s going to take me the next six years, that couldn’t possibly amount to a living wage.

You dedicate this book to your mother and write very eloquently about how translating Ovid’s Metamorphoses while she was dying was a kind of consolation. How so?

Ovid is describing a state of transformation again and again and again, shifting from that character to this person, to that deity to that animal. That was the thing that enabled me to translate, if you will, what was happening to her body as a metamorphosis. In some sense, death is a metamorphosis from living to dying, your body literally alters to a state in which it is no longer functioning. It was the fact that I was so deeply immersed inside of a poem that was so attentive to that, to that reality of what happens when we die. I found that really revelatory and difficult to take in, but I had to take it in because it was happening in real life.

Here, in her own words, a few of Lahiri’s favorite things.

“The glass-top table was given to me by my friend the poet Alberto de Lacerda. He taught me at Boston University in graduate school. It has been beside my reading chair since 1997. On the table is a copy of Oliver Twist I bought in the bookshop in the home of Charles Dickens when I was 12 years old. It was the first time I set foot in an author’s home. It was so thrilling. On top of the book is a list. When I was in college, I took a Shakespeare course with Edward Tayler. He wrote down these six points, kind of a road map to how to write; it felt like he was an oracle. The jar with shells and rocks in it is a sampling of the things I pick up on the beach when I’m in Wellfleet [Massachusetts]. I can’t really be at peace if I don’t have a piece of the sea in my house. Behind it in a box frame is a Roman postcard of a young woman playing a double pipe that I discovered and grew attached to long before I ever went to Rome. It’s very powerful to be drawn to something that you don’t realize comes from a place that’s going to call to you and become another home. In front of that is a statue of Saraswati, the goddess of learning, given to me by an aunt of my mother’s in Kolkata who was a Sanskrit professor. She gave it to me as a kind of talisman for my studies, and I’ve kept it by my desk since my college years. In the large frame is a watercolor by my grandfather. I believe this was from his imagination, not from being in Kashmir, which is the landscape. The marbled-paper box on the table is the first object from Italy I ever possessed. I keep my pen cartridges inside of it. The perfume bottle on top of the box belonged to my mother. She died a year ago. She was not a very vain person, but she loved fine perfumes. She used the stopper to apply vermillion to her hair, which is the traditional symbol of a Bengali married woman. If you look carefully, you can see the stain of the vermillion powder that she would apply to her hair parting around the base of the stopper.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

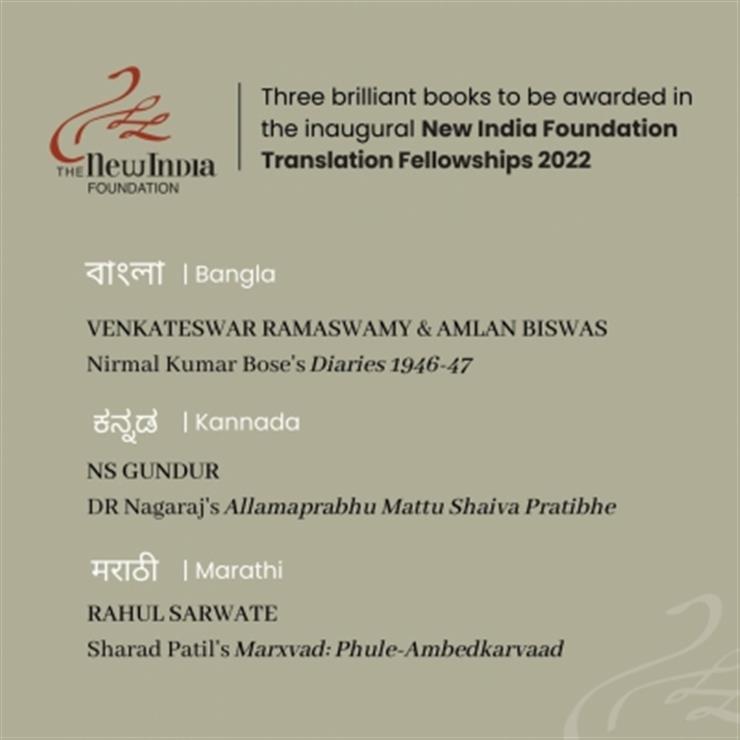

NIF Translation Fellowship awardees announced - Punjab News Express - Translation

NEW DELHI: The New India Foundation announced the three awardees of the inaugural NIF Translation Fellowships, chosen from across 10 Indian languages for the research and translation of three historically significant non-fiction texts originally published in Bangla, Kannada and Marathi.

Instituted to promote non-fiction translations from various Indian languages to English, the Translation Fellowships are envisioned to create an expansive cultural reach for works that have thus far been confined to those who understand the original language of their composition.

The awardees of the inaugural round of the NIF Translation Fellowships are Venkateswar Ramaswamy (literary translator) & Amlan Biswas (statistician), who will translate Nirmal Kumar's 'Diaries 1946-47' from Bangla, NS Gundur (academician and literary historian) who will translate DR Nagaraj's 'Allamaprabhu Mattu Shaiva Pratibhe' from Kannada and Rahul Sarwate (academician and historian) who will translate Sharad Patil's 'Marxvad: Phule-Ambedkarvaad' from Marathi.

Awarded for a period of six months with a stipend of Rupees 6 lakhs to each recipient/team, the Translation Fellowship offers the opportunity for direct mentorship under the Language Expert Committee and the NIF Trustees, apart from providing financial, editorial, legal, and publishing support.

There are no constraints on genre, style, nationality of the translator, or ideology of the material chosen for the Translation Fellowships as long as they are published after 1850 and illuminate the development of modern and contemporary India.

The Jury for these fellowships included the NIF Trustees: political scientist Niraja Gopal Jayal, historian Srinath Raghavan, and entrepreneur Manish Sabharwal alongside the Language Expert Committee in all 10 languages, comprising bilingual scholars, professors, academics, and literary translators.

Speaking on this initiative, Niraja Gopal Jayal, Trustee of New India Foundation said, "The Translation Fellowships of the New India Foundation have been awarded for the translation of three books that span the genres of personal memoir, philosophical dialogue, and critical theory, by three towering intellectuals of their time: Nirmal Kumar Bose, DR Nagaraj, and Sharad Patil. Written in Bangla, Kannada and Marathi respectively, each book is a fine contribution to the rich intellectual tradition in these languages. We are excited that this work will be introduced to readers through annotated translations and hope that the English editions of these books will spark conversations about the relevance of their ideas today."

NIF Translation Fellowship awardees announced.(photo:@newindiafndtion/Twitter)

For clarifica

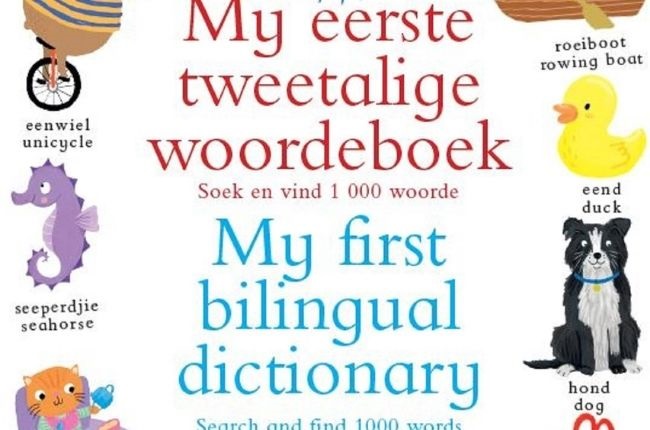

New bilingual dictionary offers tons of fun to children learning Afrikaans - News24 - Dictionary

"Children can explore their world with this fun first dictionary and learn the names of various things around them." Photo: Book Cover.

Miles Kelly, a UK publishing house, has published a fun bilingual dictionary for kids.

The lovely, large, hardback book full of colourful pictures and descriptions makes learning Afrikaans and English tons of fun.

Children can explore their world with this fun dictionary and learn the names of various things around them.

Read: Browse local children's stories in all official languages

Each page of the bilingual dictionary is packed with pictures and things to find and talk about. It is full of colourful illustrations, which keep children engaged.

This bilingual dictionary was published in March 2022, and it is sold at R260,00 per copy. Find out more at NB Publishers.

Chatback:

Share your stories and questions with us via email at chatback@parent24.com. Anonymous contributions are welcome.

Don't miss a story!

For a weekly wrap of our latest parenting news and advice sign up to our free Friday Parent24 newsletter.

Follow us, and chat, on Facebook and Twitter.

We live in a world where facts and fiction get blurred

In times of uncertainty you need journalism you can trust. For only R75 per month, you have access to a world of in-depth analyses, investigative journalism, top opinions and a range of features. Journalism strengthens democracy. Invest in the future today.

Thursday, April 21, 2022

Asadollah Amraee and Arezoo Salari on the Process of Translating The Elephant of Belfast and Its Resonance in Iran - Literary Hub - Translation

In June of last year, I connected with scholar, journalist, and translator Asadollah Amraee through my friend and fellow Counterpoint author, Karen Bender. She had posted about the recent publication of my debut novel, The Elephant of Belfast, a historical narrative about the German blitz on Belfast and the female zookeeper, Hettie Quin, who cares for a young Asian elephant during the devastating bombings in the spring of 1941. Amraee, aware of the book, said that he was interested in a Persian translation, and thus, this unexpected collaboration began.

Via messages on Instagram, I soon met fiction writer and translator Arezoo Salari. Because Iran doesn’t recognize international copyright law, there was no contract, but instead, there was an unspoken agreement of mutual respect. (In addition, some of the romantic scenes were cut to make the book publishable in Iran.)

A few months later, Salari let me know that the novel would be published and distributed by Gooya Publishers, a well-respected publisher in Tehran, and then, on March 12, 2022, she sent me a short video of فیل بلفاست on display in a bookshop dedicated to Gooya books in the Behjat Abad neighborhood of Central Tehran. From the initial email to publication, the process took about nine months, short in publishing time.

Up until this point, most of my understanding of Iran came through a close friend here in Austin, Dena Afrasiabi, a fiction writer and publications manager at the Center of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas. Dena was born in Shiraz, and her family left Iran in 1983 when she was almost two years old. Her mother and Dena traveled to Sweden, where her family was living, and later her father joined them. From Sweden, Dena’s family traveled directly to Los Angeles, where her father had a research fellowship to study AIDS (before it was known that it was caused by HIV) at UCLA.

Fiction translation has always been a fine matter for me and it is, in fact, a way of communication and dialogue with other people in this troubled world.More than eight years ago, I met Dena through the literary community in Austin. Before the pandemic started, she taught me a Persian phrase related to the heart. (At the time, I was experiencing considerable grief because I had lost both my parents, about ten weeks apart.) In Persian, Dena explained to me that the phrase “thick-skinned” can be translated as پوست کلفت [poost-koloft], which is similar to the English phrase, as poost literally means “skin.”

But the phrase “thin-skinned” is translated as دل نازک [del-nazok], which doesn’t carry the slightly negative connotations of the English, as del means “heart” (metaphorically) or “inner being.” While in English, you’re either thin-skinned or thick-skinned, in Persian it’s possible to be both at the same time. For your outer skin to protect you, while the skin around your heart stays porous.

While writing The Elephant of Belfast, I was interested in exploring the way cycles of violence, light, and darkness can transform individuals and animals during extreme moments of brutality. Later, after Dena explained the above phrase to me, I realized that I was also attracted to this notion of experiencing two emotional states—of being thick-skinned and thin-skinned—at once. This is our shared human experience, our shared language, in a way.

I’m very honored that Salari and Amraee chose to translate and publish my novel, to bring this particular story of war, humanity, and animals to their country of readers (a story that is unfortunately repeating itself during the Russians’ horrific invasion of the Ukraine). As a reader and a writer, I learned so much during the process. Below, I interviewed Salari and Amraee about the undertaking of translating my novel and the world of contemporary publishing in Iran.

*

S. Kirk Walsh: How did you first hear about The Elephant of Belfast? What attracted you to the novel as a possible title for translation for Iranian readers?

Asadollah Amraee: I first read about The Elephant of Belfast in Kirkus Reviews. We suffered a long, imposed war—and Iranian readers are very familiar with war-torn situations. As far as I know, novels, like The Elephant of Belfast, attract Iranian readers. Usually, I recommend my friends and my students and ask them to translate works of modern writers. I proposed Arezoo Salari to translate your book into Persian—and I am very glad she did it.

Translation is considered a form of intercultural communication involving the cooperation of many agents.SKW: Was there a particular aspect of the story that you think will resonate with readers in Iran?

Arezoo Salari: Most of the free people of the world hate war, especially religious wars. In Iran, too, most people wish that one day the weeds of war would dry up all over the world. War is the darkest stain of human history that can be reduced to ashes with just one signature, romantic dreams, childish laughter, and the hopes and aspirations of one or more generations. This experience can cause a common emotional arousal in the readers of the novel.

AA: Fiction translation has always been a fine matter for me and it is, in fact, a way of communication and dialogue with other people in this troubled world. Readers gain more knowledge of different spheres. In a world of limitless new content, one should have a meaningful matter for the reader. The Elephant of Belfast is going to provide the reader with insight into war and cultural differences between two nations and the vulnerable wildlife and animals who are victims of war and rebellion.

SKW: Could you talk about the translation process of this novel? What was your approach to translating to the text?

AS: I am a writer in Persian in the first place, so I did my best to choose the most beautiful words and terms. Sometimes I would search for synonyms for some words and then choose carefully. In fact, I was trying to use my own writing ability to introduce the real writing style of the author while translating.

SKW: What are the priorities for you while translating a text? Are you more interested in tone, style and meaning than word-for-word accuracy?

AS: Certainly both have their special importance. Iranians have a very rich culture in literature and have great writers throughout the long history of their civilization. They touch literature in the best way and cannot be absorbed by surface or cheap content. This makes writing and translating for Iranian readers very difficult.

AA: I am interested in the tone and style. I prefer to read for pleasure and a better understanding and share it with the reader. Although the author is a creative mastermind of the literary work, in my country the translators are one of the main factors for gaining more readership for a novel or a short story collection or anthology. The more famous writers gain more readers, but the name of the translator always appears on the book cover.

SKW: How did you deal with creating a sense of place in the translation, since the novel so carefully constructs the atmosphere of World War II Northern Ireland through style and dialogue?

AS: I was a child during the Iran-Iraq War, and I was never in the real world of war, but your descriptions nailed me. So long after the translation I could smell the gunpowder, the cold of the dead, the distress of displaced people, and the tears and fear of children. I felt the atmosphere as if I had experienced it. During the translation, I was sometimes overwhelmed by the fear, despair, and grief of the city of Belfast, and I was worried about Hettie.

SKW: What are some of the challenges of translating from English to Persian that most readers might not be aware of?

AA: Translation is considered a form of intercultural communication involving the cooperation of many agents. There are many challenges in administrative and governmental levels supervising the publication and book industries. The government has not ratified the copyright convention—and this allows other translators and publishers to retranslate some works several times, even when some publishers buy the rights of a book. There are some publishers who observe the copyright convention even though the government is not a member of the convention. As a result, there are social and financial challenges facing translation as a profession in Iran.

So all I understood as a reader—not as a translator—was the darkness and suffering that can affect this short life during wars.As a translator, one might be a true logophile, but most readers want to see words they understand without reference to a dictionary. Sometimes the translator might encounter jargon that is newly coined. In this case, the writer is helpful more than any dictionaries and references and may explain the meaning of unfamiliar words the first time you use them. There is a contract of mutual agreement and permission. This is very helpful.

AS: There are many challenges. For me, proverbs and idioms are difficult. On the other hand, because of the structural differences between all languages and changing the meaning of a word by adding suffixes and prefixes, a translator must know a wide range of words and terms. In addition, the translator must know the writing style and synonymous words to beautify the texts, especially literary texts. Otherwise, the translator can destroy the author’s work in the destination country.

SKW: What do you hope Iranian readers will get out of reading The Elephant of Belfast?

AS: People who study in Iran and look for books are often people who know what they are looking for. So all I understood as a reader—not as a translator—was the darkness and suffering that can affect this short life during wars. A life can be spent sweetly in peace, love, and security. Being bound by human mortality and commitment to one another—which has diminished today—can create a highlight in the reader’s mind throughout this story. For example, the abandonment of the family by the father and the depression of the mother, which is very common these days.

SKW: What are some of the challenges of distribution in Iran?

AA: The publication process is very complicated here. Some famous titles and much-praised titles are translated and published by several translators in different publishing houses. Take for an example, Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro. Right now, it has eight translations even though one of the translations obtained the permission of the writer and the copyright.

After the authorities in the book office of the Ministry of Culture issues the permission of the book’s release, the publishers distribute the copies to book-distribution companies and they go bookshop to bookshop and offer the newly published titles to the booksellers. Although nowadays some publishers have their own bookshops and the online sales are also a common procedure.

SKW: How many English titles are translated into Persian each year?

AA: Many books are translated and distributed every year in Iran. I have translated The Paris Hours by Alex George, which I obtained the copyright for. Before that, I translated The End of the Story by Lydia Davis. Paul Auster, Margaret Atwood, Raymond Carver, Harry Potter, Philip Roth, and many Latin American writers are very popular here. I must add the English classic titles and modern classic writers like Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck and so on.

AS: This statistic varies from year to year. For example, in 2020, this number was around 25 to 30 thousand titles.

SKW: What is the next project you’re working on?

AA: I am preparing the third collection of Ben Loory’s stories. I have translated his previous titles: Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day and Tales of Falling and Flying. I am also translating the second book of Sandra Cisneros, too.

AS: I am writing a collection of short stories in Persian. After that, I will translate Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Gravel Heart for Morghe-Amin Publications.