My father was born and raised in Norway, and I’ve spoken the language since living there for seven months when I was 12. In 2003, while visiting family in Oslo, my Dad’s cousin and her husband (who I consider my aunt and uncle) introduced me to the work of Jon Fosse. I read Fosse’s play Vinter (Winter) in his original New Norwegian (nynorsk), and later that night went to see the National Theater’s production at Torshovteatret in Oslo. I was blown away.

From a formal written aesthetic perspective, Fosse’s play was unlike anything I had ever read before, and it moved me deeply. It looked like poetry on the page, with lots of white space, no punctuation, and clear musicality. The story was a simple, everyday encounter between two people, but it resonated on a universal scale in all its complex silences. The text begged to be spoken aloud and was imbued with layers of subtext; the pauses were clearly just as important as the words. I felt I’d stumbled across the most important writer of our time. When I saw the performance that night and read in the program that Fosse had already been translated into over 40 languages and produced all around the world, I couldn’t understand why no one had brought his work to the U.S. yet.

Fosse’s acknowledgment of time and our own vulnerability illuminates our existence and creates real possibility for positive change.

When I got back home to New York, armed with Fosse’s complete works in Norwegian, I searched the NY Public Library for an English translation to share with potential producers and collaborators and found only one: a British translation of Natta Syng Sine Songar (translated into: Nightsongs—which I found strange, because the original title is inherently poetic in its literal translation: the night sings its songs.) I reached out to Jon Fosse over email and boldly asked for the rights to produce and direct his U.S. debut production. To my surprise, he answered enthusiastically within two hours.

As we continued our conversation, Fosse acknowledged the challenge of translation and encouraged me to consider translating specifically for production in New York. He sent me two other attempts at American-English translations of Natta Syng Sine Songar. I read the first few pages of each, but one felt too literal and highlighted the foreign nature of the work while the other felt like it was trying too hard to sound American. I remember looking back at Jon’s original text in nynorsk and then reading the first few pages of the British version. And suddenly I realized that none of them were articulating quite what I saw and felt when I read his work in nynorsk, or when I saw it on stage in Oslo.

To our American ears, the British translations render Fosse’s characters higher class than how he writes them. I had initially thought it could be ok to replace a few British idioms with American ones, but as I skimmed those first few pages of the British text, I saw implied class differences everywhere, in every character.

For example, in the second scene of Natta Syng Sine Songar / Night Sings Its Songs (which is how I would later translate it), The Young Man says to his father, The Old Man: “Du må berre setje deg ned,” which the British version translated as “Do sit down.” This might work well for a British audience, but for New Yorkers, this would sound stuffy and pretentious. While the characters clearly had some awkward family dynamics in the room, my understanding from the nynorsk was that this family was not nearly so formal. I asked myself: why on earth would we put this delicate poetic text through a British sensibility in order to reach us on this side of the pond? [Later, I would decide to translate this line as: “Have a seat.”]

Instances like this presented themselves on every page of the play, in the syntax of so many common phrases. If Fosse’s work was going to resonate with my New York audience, it would be vital that his characters read as everyday people. They needed to feel like you or me.

So I returned that British translation to the library, deleted the other two electronic files that Fosse sent me, decided to only look at his original text in nynorsk from that moment on, and with the encouragement of Fosse and my dad, I became a translator. Although I had never translated much more than emails from family, let alone one of the world’s most produced playwrights, as a director, I knew what it takes to make text work onstage and how to create a good piece of live performance—with moments of surprise and tension, moments that are full of possibility. So I threw my heart and soul into the task at hand.

From a technical perspective, Fosse uses words sparingly, with no punctuation except for line breaks and the choice between beginning each line with a capital letter or a lowercase letter. Words, phrases, and ideas are repeated in variations. Sparse dialogue builds slowly, repeats, connects, shifts slightly, and accumulates to create suspense and a powerful sense of rhythm. His poetic form makes every word vital and extremely active. The most common words sometimes convey vast existential ideas.

One such word that appears again and again (over 150 times, in fact) in Natta Syng Sine Songar is “ja”—I had noticed that this repetition was missing in the British translation, and instead the translator had chosen to replace each “ja” with what he thought it meant in each given moment—which often meant “yes” and sometimes deleting it entirely, when it seemed like filler word. But the repetition felt critical to me for several reasons: 1) the everyday quality of the word as it is spoken, not written, 2) the way this “ja” could function to build tension between live performers, 3) and how it unites the characters despite the vast space between them.

I spent a lot of time workshopping how to best translate this one small word. The first time I gathered some actors to read the play out loud, I gave them a piece of paper that had a list of all the words they could insert when they saw the word “yeh” in their script. To my surprise and delight, they all chose to play with the repetition rather than find alternatives. From my final translation notes:

Norwegian “ja” = yes = yeh

Yeh = the most common version of an American “yeah”, only not so nasal, and not necessarily enthusiastic.

Yeh = yep, hmm, ok, so, well, fine, oh, sure, yeah, uh-huh, tsk, ugh…basically all the filler words—how we speak, not how we write.

This is part of what is revolutionary about Fosse’s work—he finds the simplest way to say something, and within this everyday speech, there is deep complexity through repetition and slight variations. It is both simple and complex, both realistic and very heightened at the same time.

This is the reason I was so attracted to Fosse’s work—the way that potential hangs in the air, the way his characters represent all of humanity in the turn of a phrase, the way the past merges with the present and the future. Standing still is a primary action and “moving towards each other” is what happens next. Location is immaterial, but every breath, every turn of phrase, and slight physical action is important. So is the wind, the rain, and the sea. Death is always present, and its constant proximity challenges characters and the audience to assess their humanity. Fosse’s acknowledgment of time and our own vulnerability illuminates our existence and creates real possibility for positive change. Every time I entered Fosse’s world , I was reminded that we are only on this planet for a short time and must be brave enough to take action while we are here.

Sometimes I would sit with a few lines for days, and then discuss with my brilliant dramaturgs (one Norwegian and one American) all the possibilities of what could happen during this particular moment in performance. It was a group effort, and eventually we would land on what felt like the closest to Fosse’s nynorsk, acknowledging that we would never get there completely—it was an impossible task, like moving towards infinity. Always getting closer to both the specificity and the openness.

And so I came to embrace an idea that stems directly from Fosse’s text and would define my translation (and directorial and overall artistic) approach: specific ambiguity. The goal was always to be as specific as possible with every word/phrase I chose, but to create enough room for multiple interpretations from any person who receives it—whether that be actors on stage, or people in the audience. Onstage, this meant directing the actors to consider all the possibilities of which action they could take in any given moment, and then keep all those choices alive in their body even after making a choice. It also meant encouraging actors to keep their choices to themselves and be comfortable with disagreeing with their scene partners about what was happening in a given moment. This was not always easy, but it meant that the audience was confronted with their own mysterious piece of art, and they had to translate it through their own sensibility in order to take in and make sense of what was happening.

I learned to listen—to the silences between people, to what’s happening in a breath, and to the more than human world.

The first time I met Jon in person as I was halfway through the translation process of Natta Syng Sine Songar / Night Sings Its Songs, with a solid draft, but not honed yet. I shared my directorial vision with him, and the lines in the play upon which my vision was hanging, when The Young Woman, in a moment of crisis is searching and says:

DEN UNGE KVINNA THE YOUNG WOMAN

Veit du det You know

at alltid skjer berre eit eller anna that something or other always happens

Eg liker ikkje at noko skjer I don’t like it that something happens

Alt skal helst vere roleg I’d rather everything stayed calm

og berre det vante and that only the usual things

det ein kjenner til things that you’re used to

skal skje would happen

Men så skjer jo alltid noko uvanleg But something unusual always happens

Alltid Always

He looked at me and said (something like): Du forstar stykket. (You understand this work). His confidence—that I could translate his singularly spiritual perspective and capture it in my own theatrical language, finding simple words and actions to convey his vast existential ideas—that faith powered me through so many of my early days and made my commitment to creating the best possible translation and production even stronger.

Then during that first rehearsal process, whenever I would write to Fosse with a question—often about what was happening in a certain moment—he would usually respond: “You know the answer, Sarah.” As a young artist at the beginning of a new millennium, I was searching: what did I have to say? Fosse’s unwavering trust in me meant that I had to trust myself. I had to slow down and tune into my vision for the work, translating the play Norwegian to English, then page to stage—as I saw it, heard it, and felt it.

Through the process of working with six of Fosse’s masterful texts over the next 11 years with him as a friend and collaborator, I found my voice as an artist. I learned to slow down and be still. I learned to listen—to the silences between people, to what’s happening in a breath, and to the more than human world. I learned about philosophy, duration and time, scale, resilience, and survival.

All of this learning fed directly into my next decade of artistic practice. My project, 36.5 / A Durational Performance with the Sea, was created over nine years on six continents from 2013-2022, and was a different act of “translation,” but very much informed by my ethereal Fosse productions. Moved by Hurricane Sandy’s impact on New York City, I felt an impulse to translate the seemingly abstract concept of sea-level rise into an embodied experience. It began as a small poetic gesture—I walked out into the sea to listen to water as it rises with the tide—and this turned into a series of large-scale participatory performances and video works made with communities around the world. Hundreds of people joined me standing in water and thousands witnessed from land and through livestream. Whether they know it or not, what everyone experienced was an intentional act of specific ambiguity—tiny vulnerable humans standing still in a vast landscape, looking towards the sea, flirting with danger, helping to create an open-ended image that contains layers of meanings, inviting the participants and audience alike to reflect on their own humanity. Just as Fosse asked of me.

*

MAY 6, 2024: 11am-9pm at the Segal Theatre in the Graduate Center, CUNY

Join Us! Oslo Elsewhere reunites 20 years after the U.S. debut of Fosse’s work. For an all-day event to hear experimental readings of five plays by 2023 Nobel Laureate Jon Fosse, in Sunde’s American English translations.

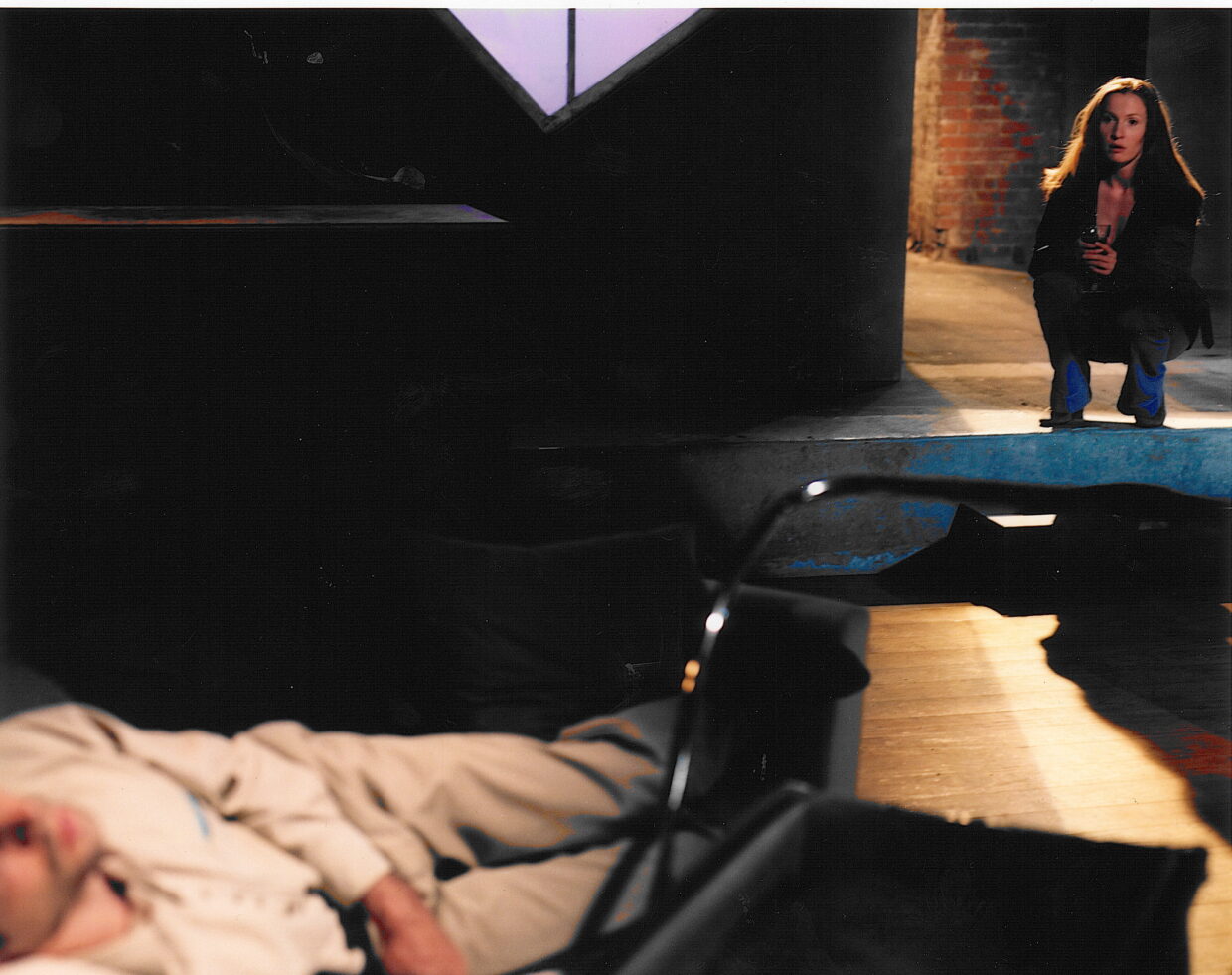

Featured image: Tom A. Kolstad/Det norske samlaget via Creative Commons 4.0

Adblock test (Why?)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/a-teen-slang-dictionary-2610994-Cindy-Chung-cfb7f3b3ac364bf1aeb9e730246acf51.png)