In the publishing world, fall is for Big Books: hyped debuts, new releases by heavy hitters, major political titles.

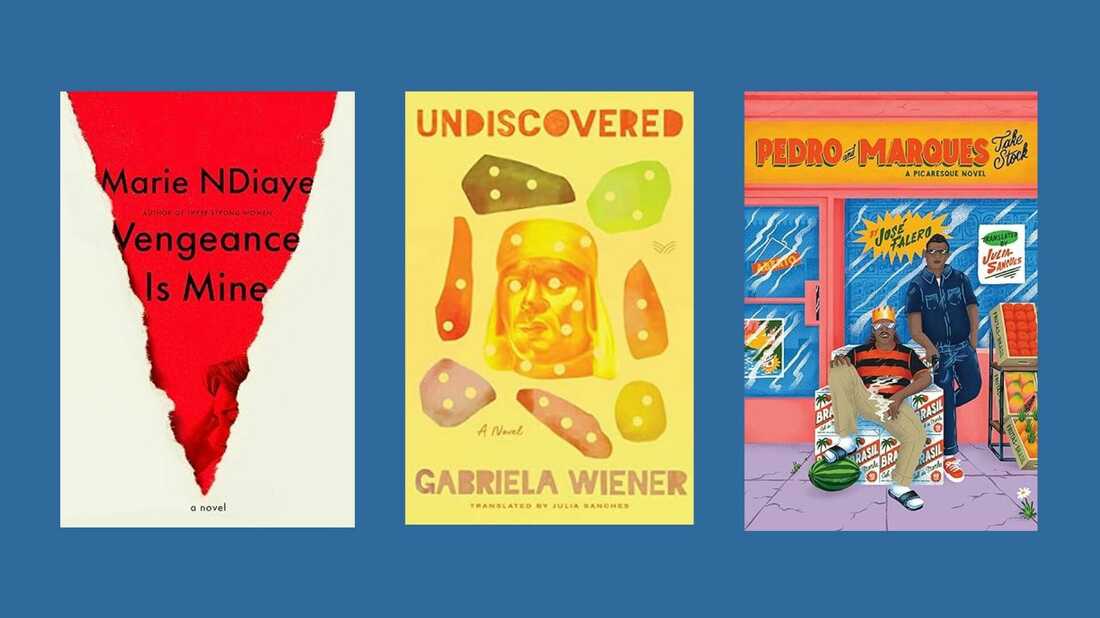

One of the three titles below, Marie NDiaye's Vengeance Is Mine, belongs indisputably to this category. NDiaye is one of France's most significant living writers, a David Lynch-like creator of spooky and mystifying worlds. The arrival in English of a new NDiaye novel is cause for both celebration and fear.

I feel the same way, though for quite different reasons, about Undiscovered, the Peruvian writer Gabriela Wiener's new novel. Wiener, who is known mainly for her nonfiction, is a major voice in Peruvian literature, and her two prior English-language releases, Nine Moons and Sexographies, earned admiration and acclaim for their direct discussions of sex, desire, and pregnancy. Wiener's honesty can be just as alarming, in its way, as NDiaye's bubbling swamps of emotion — and, slowly but surely, is earning her not just a big Anglophone readership but, more importantly in the long term, a devoted one.

Pedro and Marques Take Stock, José Falero's first book to be translated from Portuguese to English, isn't big in the way Vengeance Is Mine is and Undiscovered may be. It's a picaresque set in Porto Alegre's poor neighborhoods, a mix of crime writing and social commentary. It's tough to guess, reading it, whether Falero's future work will lean more toward the former or the latter — but it's clear that he's got both talent and ideas to burn. We're going to see more José Falero, and Pedro and Marques gives readers a chance to get in on the ground floor.

Pedro and Marques Take Stock

The Brazilian writer José Falero's Marxist crime novel Pedro and Marques Take Stock opens with its two heroes — who work in (and sometimes steal from) a grocery store in Porto Alegre — assessing their lives. (Julia Sanches, Falero's translator, deserves great credit for getting the title, and much else, so right in English: Pedro and Marques take stock of their lives while taking stock from the store's shelves.) Both men live in entrenched poverty: the ceiling of Marques' house is rotten, as is the floor of Pedro's. At the book's beginning, both are newly determined to escape.

Pedro is the novel's intellectual, a self-taught philosopher who has made the bumbling Marques into his "disciple." For him, figuring out how to get rich is both a personal challenge and a social one, a way to defy a world that's so stacked against him that, he decides, "Not even prison or death could be worse than his shitty little life." Marques, meanwhile, has a ticking clock: His wife Angélica tells him in the book's opening chapters that she's pregnant with their second child, and they can hardly afford to care for their first. Only such pressure, Falero suggests, could get Marques to agree when Pedro decides the best way for them to get rich is to begin selling weed — a safe endeavor, he feels, since Porto Alegre's gangs traffic only in crack and powder cocaine.

Much of Pedro and Marques Take Stock is given over to Pedro's ideas: first in monologue form, with Marques as his listener and occasional interlocutor; then to their manifestation. The drug-dealing scheme takes off quickly. Once it does, Falero all but leaves his heroes' inner lives behind. He abandons Pedro's idiosyncratic version of Marxism, too. It's frustrating to get kicked out of the protagonists' heads, and a surprise to be told three-quarters of the way through the novel that Pedro, our philosopher, has suddenly become "free from his conscience." But though Falero's abandonment of character is a disappointment, his writing, in Sanches' translation, is snappy and slangy enough to keep the reader going, with enough lyric moments to surprise. Pedro and Marques Take Stock is, ultimately, a caper, if one that promises more big ideas than it provides.

Vengeance Is Mine

Reading the acclaimed French novelist Marie NDiaye is always a disorienting experience. NDiaye, who has won France's Prix Femina and Prix Goncourt and received a Kennedy Center Gold Medal for the Arts, is a master of emotional obfuscation. Her characters rarely understand why they're doing what they're doing, and yet their feelings and instincts are far too powerful to resist. In Vengeance Is Mine, her tenth novel to appear in English, this is truer than ever. Its heroine, a Bordeaux lawyer named Maître Susane — Maître, as translator Jordan Stump explains in a brief note preceding the text, is a term of honor for French lawyers; NDiaye never reveals her protagonist's first name — is quietly but fervently obsessed with her Mauritian housekeeper Sharon. She entertains a stream of "charitable, uncontained, ardent thoughts" toward her. She is also convinced that she had a formative childhood experience of some sort with her client Gilles Principaux, who has hired her to defend his wife Marlyne, who murdered their three children.

NDiaye describes the Principaux case at chilling length, juxtaposing Marlyne's undeniable mental illness and pain with Maître Susane's murkier situation. It's quite clear that meeting Gilles Principaux has triggered some sort of crisis or collapse in the lawyer's mind: At one point, her mother tells her, "You're suffering the way you do in a dream, it's real to you but it doesn't exist." But in Vengeance Is Mine, like in many NDiaye novels, reality is dreamlike: foggy, unsettling, and sinister. By the book's end, the very idea of a coherent reality seems laughable. The world is terrifying, and nothing makes sense. Why should a character's inner life — or a novel, really — be any different?

Undiscovered

Gabriela Wiener's novel Undiscovered, translated by Julia Sanches, opens with a Peruvian writer named Gabriela in Paris, staring at an anthropology museum's collection of "statuettes that look like me [and] were wrenched from my country by a man whose last name I inherited." Gabriela's great-great-grandfather, Charles Wiener, born Karl, was a Viennese Jew who reinvented himself as a French explorer; he wrote an enormous, racist book called Peru and Bolivia, looked for but did not find Machu Picchu, and looted a tremendous amount of art from Peru. All this is true in both Undiscovered and its author's real life, which blend freely in the novel. Undiscovered is an exploration of paternal legacy on all fronts, including the divine one: "All of us have a white father," Wiener writes at one point. "By that I mean, God is white." Generally, though, she's less interested in God than she is in Gabriela's tortured relationship with her great-great-grandfather's memory and her not-much-calmer one with her father, whose death she is grieving and whose tendencies toward adultery, jealousy, and deception she fears she's inherited, though she had hoped her open, polyamorous marriage would preclude such things.

Undiscovered has an appealingly raw, confessional tone, but its prose is highly polished. Sanches' translation does not have an extraneous word. It is also — fittingly, for a book about post-colonial history — committed to retaining the original text's Peruvian-ness. Gabriela refers to Charles Wiener as a "huaquero of international repute," explaining that "huaquero, meaning graverobber in Spanish, comes from huaca in Quechua. This is what people in the Andes call their sacred places." The words huaquero and huaquear reappear throughout the novel, reminding readers that, though much of the book is set in Paris and Madrid, it is very much rooted in Peru. Gabriela, who calls herself "the most Indian of the Wieners," cannot forget that: In Sanches' exceptional translation, neither can anyone else.

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, and critic. Her first novel, Short War, is forthcoming from A Strange Object in 2024.