How Emily Wilson Made Homer Modern

Some three millennia ago, a blind bard whose name in ancient Greek means “hostage” is said to have composed two masterpieces of oral poetry that still speak to us. The Iliad’s subject is death, and the Odyssey’s is survival. Both plumb the male psyche and women’s enthrallment to its bravado. “Tell the old story for our modern times,” Homer entreats his muse, in the Odyssey’s first stanza. The translator Emily Wilson took him at his word. Her radically plainspoken Odyssey, the first in English by a woman, was published six years ago. Her Iliad will be published in two weeks.

On a recent summer evening, Wilson surveyed the view from a precipice above Polis Bay, in the quiet village of Stavros, on the northwest coast of Ithaca. A shrine in the town square shows the floor plan of a ruin, not far away, that may be the palace of Odysseus. She pointed to a crescent beach five hundred feet below, slung like a hammock between two mountains. The cave at its far end was a site of Mycenaean goddess worship, and relics recovered from it include a set of bronze tripods which fit Homer’s description of gifts that Odysseus received from the Phaeacians. “We’ll swim there,” she said.

Wilson is fifty-one, with expressive features that radiate alertness, and a lithe, sinewy physique—more Hermes than Hera. She set a brisk pace on our hike down the mountain. As I watched from the deserted beach, she plunged into the water and headed for the cave with rhythmic strokes. The bay was glassy until a breeze ruffled its surface with purple shadows, suddenly making sense of Homer’s “wine-dark sea.” It was Wilson’s first visit to Ithaca. “I felt the presence in that sea of protective deities,” she told me later, though she hastened to add that, elsewhere in Greece, unprotected migrants were drowning in it.

On our way to Stavros, we’d passed cultivated valleys and hillsides terraced with vineyards and olive trees. But the landscape, like Homer’s prosody, is mostly rugged and austere. (Ithaca is “only fit for goats,” the poet tells us.) It wasn’t hard for Wilson to imagine the tar-blackened ships that Odysseus’ father beached in its secluded coves, and the treasure he plundered stowed in its mountain grottoes. “Old Laertes was basically a pirate,” she said fondly.

One of the grottoes is known as Eumaeus’ Cave, in honor of the faithful swineherd who tended Odysseus’ pigs and is said (improbably, given the terrain) to have fattened them on acorns there. Following Athena’s directions, we found it near the spring of Arethusa, whose black waters are alleged to be a mother’s tears for her dead son.

After a vertiginous climb through thorny underbrush, Wilson and I reached a keyhole of rock in the cliff and slid down the moss-slimed rocks at its entrance into a humid cavern that looks like a rotunda some Titan sheared in half. She had sprinted ahead of me, and when I caught up with her she was sitting on a boulder, dwarfed by her surroundings. The air hummed with birdsong, and with the bells of the mountain goats that forage in the highlands. “That sound takes you straight back to Homer,” she said.

In bringing Homer back from antiquity, Wilson also had to bridge the chasm of time that has elapsed in English literature since the first full translation of the Odyssey: George Chapman’s, in 1616. But, she cautioned, “you can’t and shouldn’t try to make all that history—layer upon layer—visible in the text. My goal was to evoke an experience like the original, using the language of the people who will read it.”

The epics were originally performed by itinerant singers who roamed ancient Greece, entertaining guests at social gatherings. Travel inflected their speech with a mixture of dialects that they patched into their recitals. In classical Athens, the singers were known as rhapsodes, from the verb meaning “to sew songs together.” Their diction was stately, but audiences of every class and age listened raptly to Homer’s graphic imagery and impassioned dialogue, scored to a propulsive beat. Wilson’s ambitious project of the past decade has been to re-democratize both the poetry and its audience. Her “folk poetics,” as she calls them, are a reproach to predecessors who have “turned a great poem into a hard one,” or into a poem of their own. She rejects historical reënactments that “archaicize” Homer’s diction—“he didn’t sound archaic to the Greeks”—and modern renovations that expand his footage. The opening of Robert Fagles’s widely admired Odyssey, she points out, uses two English words for every Greek one. Her own translation hews strictly to the original line count, and it retains the power of a storyteller’s voice to fix itself in your memory. “I write for the body,” she told me.

As a brotherhood of nomads, the bards must have imbued their songs with a yearning for nostos: the homecoming that crowns a hero’s journey. Homer keeps us in suspense about Odysseus’ nostos. He left Ithaca unwillingly to fight the Trojans and spent his youth at war. His return is disrupted by misfortunes, but “dreadful, beautiful, divine” Calypso rescues him from the sea. After seven years of captivity, her charms have palled. When Zeus finally orders her to set him free, she looks for him on her island’s shore:

A jealous goddess is dangerous, as anyone would know who had languished for ten years at Troy:

Odysseus knows how to massage an ego; that was his role in the fractious Greek camp. He’s also the con man who thinks up the Trojan horse. Homer introduces him with the adjective polytropos—literally, “of many turns.” Previous translators have called him “shifty,” “cunning,” and a hundred other things. After grappling with the alternatives, Wilson chose “complicated,” hoping also to convey the sense of “problematic.” Her first sentence—“Tell me about a complicated man”—instantly makes him our familiar: that charismatic prince who’s too impossible to live with and too desirable to live without.

Part of Odysseus’ appeal, not least to modern writers, is that he redefines heroism as imagination. “You love fiction,” Athena teases him. The decade of his odyssey passes like a dream, as episodes of hardship and violence alternate with voluptuous idylls. And the mind games he plays to outwit his captors—lusty nymphs, ravenous cannibals, vengeful gods—have, Wilson notes, “a ‘meta’ element that’s about language and storytelling.”

The Iliad feels suffocating by comparison. Its central protagonist, the demigod Achilles, is problematic without being complicated. His “cataclysmic wrath” fuels a story that begins in medias res—not with Paris’ abduction of Helen, or the massing of an invasion force, but at the end of a nine-year stalemate, with the demoralized Greeks camped on the Trojan coast and the Trojans trapped in their impregnable city. The action is compressed into about six weeks, whose grinding carnage would numb your senses if Homer’s poetry didn’t keep stirring them. Yet the Iliad’s greatness is inseparable from its claustrophobia. Against a background of blight and bleakness, the characters dazzle us with their vivid idiosyncrasy. Perhaps even more than Odysseus, they’re our familiars: beleaguered humans in tragically stressed relationships, at the mercy of fate.

Apollo sparks the conflict that will engulf them. One of his priests is a Trojan ally with a cherished daughter, “beautiful Chryseis.” Achilles captures her in a raid, and Agamemnon, the Greek commander, claims her as his war trophy. The priest offers to ransom her with a priceless treasure, which Agamemnon spurns rudely, and Apollo punishes this sacrilege with a plague. Only after the Greek armies have been decimated does their general relent and send Chryseis home. But then he consoles himself by mortally offending his greatest warrior: he confiscates Achilles’ trophy from an earlier looting spree, “fresh-faced Briseis.” And with that puerile quarrel between stubborn warlords over the right to own and to rape a girl, Western literature begins.

While Wilson was contemplating the Greeks sickening in their camp, and the Trojans caged behind their city walls, the plague of Covid forced her family of five into lockdown. She didn’t want to push the analogy (“I never thought, ‘Oh, no—Achilles has to order online groceries’ ”), but she was conscious of both how volatile confinement can be and how primal the need for company becomes. “You can either rage at the people you’re stuck with or grow more devoted,” she said.

Wilson teaches classics and comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania and lives near the campus in a rambling old house that she shares with her partner of nine years, David Foreman, an administrator at Swarthmore, and her two school-age daughters, Psyche and Freya. (Her eldest daughter, Imogen, is now in college.) When we met last May, she greeted me at her door in running clothes. I was surprised first by her youthfulness, then by the luxuriance of her tattoos. “I didn’t used to read as a tattoo person,” she told me, as we settled on the deck outside her bedroom, which is painted Aegean blue. “When you get tattooed in places that show, it changes your identity.”

Wilson’s tattoos became visible as she worked on the Iliad. They inscribe her closest relationships: with her children; Foreman; her late mother; her younger sister Bee Wilson, the noted British food writer; plus a pantheon of Greek deities and creatures sacred to them. The birds and flowers are emblems of a tender heart, while the armory of spiky weapons—a spear and a bow on her calves, the thunderclouds of Zeus on her shoulder—are badges of a fighting spirit.

That afternoon, Wilson took me for a walk through a neighborhood of abandoned factories, then along the banks of the Schuylkill River, crossing wild meadows to a glade, a route she’d chosen for its “Iliadic contrast of beauty and desolation.” Her Iliad won’t be the first by a woman, but she considers “the first-woman thing” a sexist distraction: “It slights the many brilliant female scholars who’ve worked on the poems. And no one mentions the gender of the men.” What she didn’t say, though her followers do (the flaws and merits of her Odyssey have been vehemently debated on social media), is that it slights her translations’ real singularity.

“The ancient Greeks teach one to be modern,” the poet and classicist A. E. Stallings observed to me. “They taught that to me and to Emily. It was time to strip away all the mannered layers—the tarnish of centuries—and she does that. Her translations have the freshness of the sky after a storm. Their briskness and simplicity are faithful to the oral tradition, and she brings the poems to a new generation, which struggles to read harder texts and wants clarity.” Wilson feels an acute, almost maternal sense of duty to those lay readers: “They need to trust that I’m telling them the truth, both about the language and the psychology. There are no lazy ways to do it.”

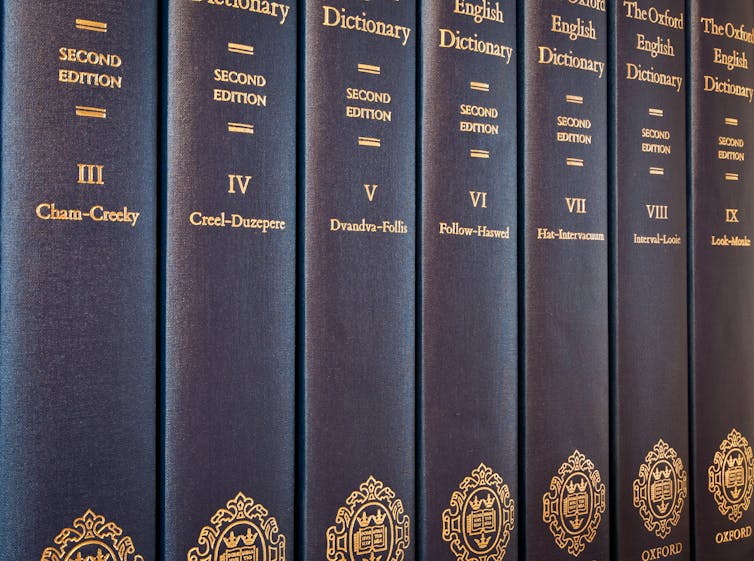

On rare occasions in her Iliad, a word would jar me: “flirty,” “flabbergasted,” “inappropriate.” Or a slangy outburst made me laugh at a dramatic moment: “Stop! You are acting crazy, Menelaus!” But that line is worth pausing to consider precisely because none of Wilson’s predecessors would have written it. Among the notable translations of the past century—by Fagles, Robert Fitzgerald, Richmond Lattimore, Peter Green, Caroline Alexander, Stanley Lombardo, Robert Graves (who pivots from prose to poetry to highlight dramatic moments; there’s a lot of mansplaining in Homerdom)—each has its strengths. Their authors are united in presuming that readers will be “improved,” as pious critics used to say, by their encounter with Homer. But Wilson reminds us that a great storyteller conceived the poems as entertainment. Her language is so vitally urgent that even the Iliad’s endless battle scenes feel, to use an un-Homeric simile, like listening to the Super Bowl on car radio. Stallings said, “Does Emily’s clarity betray that element of the epic register that Matthew Arnold calls ‘nobility’? Some critics think a certain grandeur is missing. But every translation is a compromise, even a great one.”

Wilson’s mother, Katherine Duncan-Jones, was an eminent scholar of Elizabethan literature who died in October of complications from Alzheimer’s. Her father is A. N. Wilson, the prolific English writer whose subjects as a biographer include Jesus, Darwin, Tolstoy, Milton, Hitler, and Queen Victoria. When I spoke with him in June, at the British Library, he was researching a life of Goethe. His latest book, “Confessions: A Life of Failed Promises,” is the memoir of a writer’s triumphs and travails. Among the latter, his first marriage set the high-water mark.

The Wilsons met at Oxford. Katherine was a teaching fellow, and Andrew was an undergraduate of twenty, a decade her junior. They married hastily in 1971, when she got pregnant with Emily. “Mom did all the housework and cooking and was always apologetic about it,” Wilson said. Andrew Wilson told me that he found talking to his daughter difficult: “Sometimes she was completely mute, and sometimes she would burst into tears.” Even as a little girl, Emily was conscious of her father’s rage at his vassalage to a family, for which she felt he blamed her: “I was the one who had ruined his young life by being born.” For reasons that are a bit inscrutable under the circumstances, the couple had Bee when her sister was two.

The Wilsons lived in poisonous silence, beneath a veneer of civility. (“We had a fatal gift for politeness,” as Andrew put it.) Emily often locked herself in her room, from which she heard Bee sobbing through the wall. “My parents weren’t listeners,” she said, “so it was hard for me to imagine that I could be heard.” Encouraged by her mother, she took refuge in books, and excelled in school, though she refused to say a word in class. Her other sanctuary was a world of fantasy: “For a year or two, I pretended to be a gorilla. I would thrust my lower jaw out, even though it was painful to walk around that way.” Her other alter ego was an orangutan, which referred to itself in the third person. “It felt liberating to speak in another voice,” Wilson told me. “It drove my parents completely crazy, which is also why I did it.”

When Emily was eight, a perceptive teacher saw through her camouflage and cast her as Athena in a school production of the Odyssey. (The headmaster played the Cyclops, and the children relished poking his eye out.) “It was a turning point in my life,” Wilson writes in the notes to her translation. The experience kindled a love of theatre shared by her mother; it also, she suggests, gave her a model of “human and nonhuman” shape-shifting. “Translators have to be chameleons,” she said, “leaping from a green leaf to a brown one.”

Both sisters told me that they were, at times, hostages to their mother’s depression, though they never doubted her devotion to them. Their father could be charming, but he played favorites capriciously. “One day you were the scapegoat, the next you were his chosen one,” Bee told me, over lunch in Cambridge. “It was a toxic game which served to teach us that love is conditional.” It also served to cast them as foils. In Bee’s telling, she was the “normal” one who loved comics and television, didn’t cause much trouble, and cleared her plate. Emily was the brooding “genius.” At around fourteen, she stopped eating, then coming to the table altogether, though neither parent commented on her blatant anorexia, even when she was living on apples. “As E got smaller, I got larger,” Bee wrote in a poignant essay on sisters and their eating disorders.

Unhappy families tend to spin conflicting narratives, and there would probably be no literature without them. “I found this when I was working on my memoir,” Andrew Wilson said. (His daughters are mentioned in it only in passing.) “It was my version of events, not theirs, about which I won’t comment, except to say that what they may tell you about me is true, or partially, because they felt it.” No one, however, took issue with Emily’s account of the bitter scene that took place on January 1, 1988, when she was sixteen. The Wilsons had gathered for a New Year’s lunch, and they went around the table announcing their resolutions. “My resolution,” their father told them, “is to get a divorce.”

Andrew Wilson decamped to London, where he eventually remarried and had a third daughter. Duncan-Jones went on to write “Ungentle Shakespeare,” a biography that reads the Bard’s work deeply but portrays the man as a cad. “Mom knew that great literature is written by imperfect humans,” Wilson said. Her father read “Ungentle Shakespeare” as a swipe at “Ungentle A.N.”

When Bee went to boarding school, then to Cambridge, Emily stayed in Oxford to support their mother, “who was devastated for a long time.” She read classics at Balliol and earned a master’s in English literature at Corpus Christi, but by then England “felt like the wrong place for my well-being.” In 1996, she took a blind leap. Knowing nothing about America or about Yale—“I hoped it was by the sea”—she arrived in New Haven to pursue a doctorate. Her marriage to a former fellow graduate student ended shortly after Imogen’s birth. A second union also foundered and was followed by the familiar trials of single motherhood.

Wilson’s thesis became a book: “Mocked with Death,” a treatise on the tragedy of “overliving”—a penal sentence, by age or loss, to the terminal privation of whatever made a life worthwhile. Her mother’s dementia hadn’t set in yet, but she was attracted to writers who have dramatized this “horror”: Sophocles, Euripides, Seneca, Shakespeare, and Milton. “Most of us,” she wrote, “struggle in vain to outlive our own past selves.” That struggle may not be in vain, if the self that survives it is the authentic one. But, Wilson wondered to me, how do you recognize her? “I’m not sure I have a stable identity—or perhaps it only emerges through an engagement with language.”

At lunch, Bee had wanted to show me what one of Emily’s past selves looked like, so she’d brought a family album. In a grainy photograph from the nineteen-seventies, the Wilsons pose in an English garden. The parents—a dapper young fogy with ramrod posture and a soulful, slightly rumpled bluestocking—stand behind two tidy little girls in matching sailor suits. The taller one is refusing to smile. “It’s funny, isn’t it?” Bee said. “Emily escaped to a world where people were free to express anger.”

She was thinking of ancient Greece, but her sister also escaped to an angry new country. Wilson became an American citizen last year, in order “to vote where I live,” and to engage with the political arguments raging around her. Had she not emigrated, she doubts that she would have seen the need for new Homer translations. “Being from two worlds is part of the story,” she said. In that respect, she’s also a dual national of two education systems. Her own élite schooling had come to seem cloistered, shielded by “walls of class” that also insulate some of her students. The ones who went to private schools “don’t doubt that they belong” in a classics program, even if “they have some unlearning to do,” she said. The public-school kids “need more nurturing to feel welcome. As a translator, I was determined to make the whole human experience of the poems accessible to them.”

My first visits with Wilson took place during graduation weekend at Penn, which happened to coincide with Taylor Swift concerts in Philadelphia, so the city was a zoo. Worried that I’d get stuck in traffic, she gave me strict instructions to take the trolley. I shared a car with Swifties in lamé, graduates in mortarboards, and their elders of three generations. Wilson’s chair had been endowed by the College for Women class of 1963 (Penn became coed a decade later), and the alumni who had gathered for their sixty-year reunion would celebrate her at a banquet. Many were the same age as her mother. “Today’s her birthday,” she said quietly. “She would have been eighty-two.”

When I asked Wilson about the evening’s dress code, she apologized for having “no idea.” But she typically wears something talismanic when she performs. For her readings of the Odyssey, it was often a sequinned owl T-shirt that channelled Athena. (Homer, she notes, has an eye “for things that sparkle.”) Athena is a shape-shifting goddess. She has the power to make herself invisible, and at luminous moments in Wilson’s translations, especially private ones between foes or lovers, so does Wilson. Those exchanges are often monosyllabic and charged with unspoken feeling. Her aim, she said, was “to give the characters breathing room for their ambiguities.”

That evening, her sandals paid homage to Achilles’ mother, “silver-footed Thetis”—a daughter of the sea god Nereus, who was forced to marry King Peleus of Phthia, after he had raped her with the gods’ connivance. Thetis is a tutelary spirit for Wilson: “I’ve come to see the Iliad as a poem about the pain of a goddess mother who adores her mortal child and can’t protect him. The theme of a mother’s tragic love structures the whole poem. But that anguish teaches you a hard truth: you can’t prevent your children from ever being hurt.”

The banquet was held at the Penn library, and we got there early, so that Wilson could review her notes in a quiet corner. As the guests drifted in for cocktails, a few came over to introduce themselves. One regretted that she’d never studied Greek. Another suggested that the Iliad was ripe material for “a rap musical like ‘Hamilton,’ ” and Wilson nodded politely. As a jazz group played oldies, her co-speaker, Stuart Weitzman, checked out her footwear. “I can see you’re a lady who’s into comfort,” he said. Weitzman, a Penn megadonor, is a ’63 graduate of Wharton who made a fortune in the shoe business. “I should really have planned a talk around various characters tying on their sandals,” Wilson told me later. “They abound. But I wanted to read a violent slaughter passage.”

Diffidence is Wilson’s default mode, the legacy of a childhood spent biting her tongue, but her ferocity emerges onstage. “I think there’s a tension,” she told me, “or at least for many people a surprise, in the gap between my mostly shy persona and the intensity of emotion I try to express in performance.” Her sonorous voice gives ancient Greek the rumble of a cataract, though she also brings an impious verve to passages of dialogue. In a video I watched online, Penelope might have been Lady Chatterley and gruff Odysseus her sexy gamekeeper.

Some of Wilson’s YouTube readings have an edge of zaniness; she pulls faces and changes character with comic props—a cardboard crown, cat ears, a dishevelled wig. But that night, dressed sombrely in black lace, she recited one of the Iliad’s most heartrending passages. The gods have been intriguing furiously. Thetis begs Zeus to avenge her son’s honor, although the plan he hatches will also fulfill the prophecy that torments her: Achilles can choose to either die young as a hero or live to an obscure old age.

As the story unfolds, Agamemnon is tricked into thinking that he can win the war without his greatest fighter. The Trojans’ champion—Hector, King Priam’s son—makes the most of this advantage, without knowing it’s a ploy. But a wary seer warns him to seek Athena’s favor, so he leaves the gory plain to organize a sacrifice. Back in the city (briefly, he hopes), he finds his wife, Andromache, watching the war from the battlements with a nurse cradling their infant. In the passage that Wilson read, she grasps his hand and implores him:

Achilles, she reminds him, raided her father’s kingdom, killing him and her seven brothers and enslaving their mother. Hector is torn. If he stays behind on the walls, he can defend the citadel. But the supreme imperative of the noble warriors on both sides—Achilles, Odysseus, Ajax, Aeneas, Sarpedon, Patroclus, and even foppish Paris—is, as Hector exhorts his fighters, to “be men.” A man is someone who courts death for glory, hoping that his deeds will be immortalized by a poet. (This worked out for all of the above.)

Hector tells Andromache, “No one matters more to me than you.” Yet he offers her no comfort:

Hector routs the besiegers and sets fire to their ships. The desperate Greeks throw every man they have into the field. While Achilles sulks in his tent, his beloved comrade, Patroclus, who shares his bed, bravely joins the battle in Achilles’ armor. This imposture cows the enemy, but Hector slays Patroclus anyway, sealing everyone’s fate. Maddened by grief and rage, “the best of all the Greeks” butchers the Trojans and seizes twelve of their young boys to sacrifice on Patroclus’ funeral pyre. He spears Hector through his neck, then drags the corpse around the city walls until old King Priam abases himself to beg for its return. The poem ends with the laments of three royal women—Helen, Hecuba, and Andromache—whose losses, Wilson writes, “can never be recuperated,” except in the retelling.

Wilson has spent the past decade contemplating her kinship with these warriors. “My childhood self was an Achilles,” she said, “holed up in protest, then emerging later to reveal his power. But I also had a dutiful Hector self, doomed by compliance.” I told her that I thought Hector’s speech to Andromache, with its vision of her degradation, was tinged with sadism, but she disagreed: “Brusqueness is often a mark of fear. You push people away when you worry that you need them too much.” And it rankles her that men whom she considers self-appointed guardians of the Western canon have questioned a woman’s fitness to do Homer justice. “Any woman who has lived with male rage at close range has a better chance of understanding the vulnerability that fuels it than your average bro. She learns firsthand how the ways in which men are damaged determine their need to wreak damage on others.”

This insight, and the lucidity Wilson brings to it, may be the greatest revelation of her Iliad. The poem’s machismo has often bored or estranged me, and, in more grandiloquent translations, its heroes’ mindless bloodlust obscured the pathos of boys and men who are shamed literally to death by weaknesses that they’ve been bred to suppress. Her plainsong conveys the tragedy of their bravado, and, listening to her voice, I felt it for the first time.

I met Wilson in Athens before we left for Ithaca. The city, in late June, was more crowded than Philly had been, and considerably hotter. One morning, we hiked up to the Acropolis, but the wait for tickets was two hours in the sun, so we hiked back down. Over coffee in a little square, I told her about a vintage shop near my hotel. She was delighted by the prospect of taking her girls there. Finding a treasure in a thrift store, she said, gives her a sense of accomplishment akin to “what feels so satisfying in translation. Working within strict constraints like syntax and meter is like digging out the gem from a donation bin.”

Wilson translated Homer into Shakespeare’s meter—an iambic five-foot line, natural to an Anglophone’s ear. She tuned her text like an instrument by reciting it aloud. But she avoided reading her predecessors, who suffered, in her opinion, from reading one another. None of them, she said, felt “particularly sacred, beyond Pope and Chapman, and that’s because they are both in very different ways great poets.” In writing for the body, she searched not only for the most visceral equivalent of every Greek word but for the least slanted one. Toward the end of the Odyssey, the hero’s son, Telemachus, proves that he has become a man by hanging twelve of his mother’s serving women, who have slept with the suitors besieging her. Most translators, Wilson writes, describe them as “sluts” or “whores,” terms that don’t figure in the Greek. Instead, she calls them what Homer does: “slaves,” or, in an echo of plantation culture which felt apt to her, “house girls.”

Wilson’s translations are the first in English to jettison slurs or euphemisms that mask the abjection of women in a society where a goal of war, according to the Iliad, was to rob men of their women, and where female captives of every rank were trafficked for sex and domestic labor. (Boys were, too.) Yet she isn’t aiming to generate outrage at the sexual politics of a Bronze Age patriarchy: “It’s too easy.” To the degree that she’s outraged, it’s by the sexual politics of her vocation. “The ‘faithful’ translation,” she writes, is a “gendered metaphor.” It presupposes a wife-like helpmeet whose work is subordinate to that of “a male-authored original.” To some of her critics, especially the trolls on Twitter, Wilson’s “wokeness” perverts Homer’s world view. In her own view, the biases of previous translators have distorted Homer’s “experiential truth.”

Homer’s goddesses are thrilling models of female power. Aphrodite takes her pleasure where she finds it (everywhere). Semi-divine Helen, Zeus’ daughter, has a witchy seventh sense, a ventriloquist’s voice, and a pharmacy of magic potions. In Wilson’s view, “Nothing beats Hera, dressing up with super-chic earrings and skin creams to mess with Zeus’ plans.” (Her craftiness evokes a conjugal eye roll: “She always thwarts whatever I decree.”) But the poems’ mortal women are subject to the dictates of their husbands and fathers, and even, like Penelope, of their barely postadolescent sons. None of them challenge that convention, yet Wilson is alert to the ambivalence in their stoicism. Where Andromache’s is explicit, Penelope’s is opaque. (Her name means “veil over the face.”) “Is Penelope really glad to see her husband after twenty years?” Wilson asked me. Yes, but her translation of their reunion gives us a moment to wonder:

After coffee, I went prospecting for gems at the National Archaeological Museum. Its most famous artifact is a funeral mask of hammered gold leaf that Heinrich Schliemann, the German archeologist, found in what he believed to be Agamemnon’s tomb at Mycenae. The mask, from the sixteenth century B.C.E., predates the war, if there was one, by about three hundred years, but it’s the haunting likeness of an old king with an archaic smile, and, whatever terrible crimes he succumbed to or committed, he seems to be at peace.

The ancient gold in the vitrines reminded me of a passage from Wilson’s introduction to the Odyssey. Helen and her husband, Menelaus, she notes wryly, “seem to have suffered no obvious ill effects from her escapade—beyond the fact that so many people . . . died as a result.” Their marriage, she concludes, might have been cemented by a mutual appreciation for “wonderful consumer goods.” They surely would have coveted the goods that were on display: exquisitely wrought diadems, tripods, wine cups, sword hilts, and jewelry, the likes of which Homer inventories with the concupiscence of a Sotheby’s catalogue.

If you learn one thing from the Iliad, it’s that the greed for stuff, the drive for sex, the fear of death, the bonds of love, the pull of home, the glamour of fame, plus all the insecurities—especially about virility—that generate violence in the world are still the same. I will confess that, in the next gallery, I tarried for longer than was strictly seemly at the statue of Paris—a monumental nude youth with surely the most beautiful face ever sculpted. Of course Helen eloped with him. Abduction, my foot.

When Odysseus at last reaches Ithaca, he doesn’t recognize the island. Athena has shrouded it in mist to buy him some time for plotting his revenge before he confronts the suitors. Once she unveils the landscape, Odysseus, elated, knows just where he is: in a bay like Polis, shaded by a wooded mountain. A “cave sacred to nymphs” lies at one end of the beach, and that is where they hide his treasure—the Phaeacians’ “heroic gifts of bronze.”

On Ithaca, Wilson and I often crossed paths with mountain goats, whose bleating kids rooted at their udders, but we never met a goatherd. “They’re all off composing poetry,” she said. We never met a soul, in fact. It was as if the gods had decided to reward her with a private tour of their haunts.

To reach the palace of Odysseus, we set out from Stavros a little before dusk, when the heat had abated. About a mile from the village, on a steep mountain road, we found a sign that vaguely pointed toward the “School of Homer.” Turning onto a rocky path, we climbed for another twenty minutes until an ancient flight of steps delivered us to a plateau that is one of the island’s strategic high points. In the distance, we could see Afáles Bay and, beyond it, the Ionian Sea shimmering in a violet haze.

Schliemann poked around this acropolis in the mid-nineteenth century, and many archeologists have followed him. The existence of the palace has been disputed for millennia, and alternative locations have been proposed in Cephalonia, Paxos, Sicily, the Baltic, southwestern Spain, and elsewhere on Ithaca, but the School of Homer is a contender. Its ruins were once a complex of buildings pieced together from massive blocks of limestone, and sited so that ships or strangers were visible as they approached. Whoever lived here would have given those strangers a cordial welcome, according to xenia—the sacred code of Greek hospitality, whose breach by Paris (it was bad form to run off with your hostess) led to the Trojan War.

If these are indeed the ruins of the palace, they don’t fit the Odyssey’s descriptions of a royal seat with a vast banquet hall, a storeroom secured by “dazzling double doors,” and an upper story where Penelope worked at her loom and hid herself from the rowdy suitors. A mosaic floor in one of the roofless chambers looked Roman. (Rome occupied Greece for hundreds of years.) In the seventeenth century, some of the stone was used to erect a church, dedicated to St. Athanasios. The School of Homer got its name in English some two hundred years ago, from a local priest who showed the site to a British classicist. He saw shards of pottery, perhaps Mycenaean, scattered in the rubble; Odysseus was unlikely to have been the first Achaean prince to live there.

The birds singing in this ruined choir might have told us its history, but there was no one to interpret their song. Wilson wandered off alone and spent a while looking out to sea. Later, she told me that she’d been thinking about her mother: “She was the home that I came back to.”

Nostos may also imply the yearning for a home that doesn’t exist, or no longer, or only as an ideal: a place where the people you love the most finally recognize and embrace you. “I often feel like an Odysseus,” Wilson said. “He was always reinventing himself and, like a translator, pretending to be someone else and telling that character’s story. But maybe a true self can emerge from the lies.”

When we got back to the road, a sudden apparition arrested us. The setting sun backlit a spider’s web. She hung like a dense onyx bead precisely at our eye level between a gnarly olive tree and a pine whose scent mingled in the warm air with jasmine and goat dung. Wilson whispered, “Athena is with us.” ♦

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/RPB7OOWJCWDBGQQSHA6V5Q2QUI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/CKSHTAV4GVE2RORK3EJD2DGDOU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/JS6FKGI32WJGXL6JGXGQZHAMYU.jpg)