Anxious

“Anxious” means “worried or uneasy,” but it has often been used somewhat interchangeably with the word “eager,” to mean “full of keen desire” — but that flexibility seems to be changing.

We got the word “anxious” directly from Latin where it meant essentially the same thing: worried, disturbed, uneasy, and so on.

Eager

“Eager,” on the other hand, comes directly from French, and an interesting usage quirk is that although French did have the “full of keen desire” meaning, it had many more negative meanings for the word. The Oxford English Dictionary mentions “severe,” “fierce,” “savage,” “pungent,” “strenuous,” and more. Another meaning was “sour,” and that’s one of the roots of the Latin word for “vinegar,” which was essentially “wine eager” or “wine sour.”

English also had many negative meanings for “eager” in the beginning, but they’ve mostly become obsolete, rare, or regional. Today in English, when you hear the word “eager,” you think of positive emotions.

‘Anxious’ or ‘eager’?

In the recent past, let’s say the early 1900s, usage writers started making a big deal about not using “anxious” to mean “eager.” You were eager to take your apples to the market to sell if it was just for some extra money, but you would have been anxious about taking your apples to market if you absolutely had to get a certain amount of money for them to be able to survive the winter. You’re eager for good things, but you’re anxious for bad things or things that make you worried.

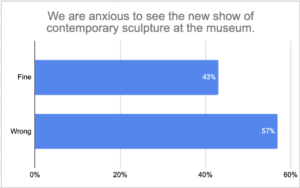

“Anxious” had been evolving, though. By 10 or 15 years ago, many people were using the words interchangeably. Three major dictionaries imply that it’s OK to use “anxious” to mean “eager,” from dictionary.com saying it’s fully standard to the American Heritage Dictionary saying in 2014 that resistance was waning. Fifty-seven percent of their usage panel said it was fine to use “anxious” to mean “eager,” and the most recent edition of Garner’s Modern English Usage says using “anxious” to mean “eager” is ubiquitous.

However, I have seen indications that resistance to using “anxious” to mean “eager” is actually growing again, which is very uncommon! When a word starts becoming accepted, it usually continues to become more accepted. But in this case, cultural factors are becoming stronger than linguistic factors. I recently did a poll on Facebook, and only 43% of the people who responded said it was OK to use “anxious” to describe an event someone was looking forward to — 14% fewer than the American Heritage Dictionary Usage Panel in 2014. That was surprising to me.

Mental health an ‘anxious’

But after reading the comments — sometimes yes, it does pay to read the comments! — it became more clear: We’ve become much more open about mental illness in the last 10 or so years, and the word “anxious” is used more frequently in a medical context. Which means that although anxiety isn’t stigmatized like it used to be, people do view it as something they’d rather not have. If you’re going to the doctor and getting a prescription for being anxious, you’re not going to associate that word with happy feelings or being full of keen desire.

The bottom line

So although usage guides no longer say it’s wrong to use “anxious” to mean “eager,” it’s probably still a good idea to keep the words separate. You’re eager to see the dessert tray at a fancy restaurant, but anxious about seeing the final bill. You’re eager to get your new puppy, but anxious about how it might get along with your cat.

Images courtesy of Shutterstock.