In Python, dictionaries are data storage objects that use a key to retrieve a value. Think of your cell phone contact list or phone book. We look for the name of the person, the key, and their phone number is the value. Dictionaries are incredibly useful when storing and sorting data. We used a dictionary in our for loop project which saw RSS news feeds used to generate content on a web page.

We’re going to go through how to create, update and delete keys and values inside of a dictionary and then use a dictionary in a real world project where we create a notification system using Python and nfty.sh.

To demonstrate how to use Dictionaries in Python, we will use Thonny, a free, easy to use and cross platform Python editor.

1. In a browser go to the Thonny website and download the release for your system.

2. Alternatively, install the official Python release using this guide. Note that this guide covers installation on Windows 10 and 11.

How To Create a Dictionary in Python

The most basic use for a dictionary is to store data, in this example we will create a dictionary called “registry” and in it store the names (keys) and starship registries / numbers (values) of characters from Star Trek.

1. Create a blank dictionary called “registry”. Dictionaries can be created with data already inside, but by creating a blank dictionary we have a “blank canvas” to start from.

registry = {}2. Add a name and ship number to the registry. Remember that the name is a key, and the ship number is the value. Values can be strings, integers, floats, tuples, and lists.

registry["James T Kirk"] = 17013. Add another few names to the registry.

registry["Hikaru Sulu"] = 2000

registry["Kathryn Janeway"] = 74656

registry["Ben Sisko"] = 742054. Print the contents of the registry dictionary.

print(registry)5. Save the code as starfleet-registry.py and click Run to start the code.

Complete Code Listing: Creating a Dictionary

registry = {}

registry["James T Kirk"] = 1701

registry["Hikaru Sulu"] = 2000

registry["Kathryn Janeway"] = 74656

registry["Ben Sisko"] = 74205

print(registry)Updating and Deleting Entries in a Dictionary.

Dictionaries are updatable (mutable in programming parlance) and that means we can update the key (names) and the values (ship numbers).

For our first scenario, we’ve had a call from Ben Sisko, and he wants his entry updated to Benjamin. We’re going to add this code to the previous example code.

1. Add a print statement to show that we are making updates. This is entirely optional, but for the purpose of this example it clarifies that we are updating the dictionary.

print(“UPDATES”)2. Add a “Benjamin Sisko” key and set it to use the value stored under “Ben Sisko”.

registry["Benjamin Sisko"] = registry["Ben Sisko"]3. Delete “Ben Sisko” from the registry.

del registry["Ben Sisko"]4. Print the current contents of the registry. We can see that the “Ben Sisko” key is now gone, and is replaced with “Benjamin Sisko”. The value has also been transferred.

print(registry)Next we will update the entry for James T Kirk. It seems that he has a new ship number (something to do with “accidentally” setting an easy password on his self-destruct app) and so we need to update the value for his entry.

1. Add a print statement to show that we are making updates. This is entirely optional, but for the purpose of this example it clarifies that we are updating the dictionary.

print("Kirk's new number")2. Update the “James T Kirk” key with the new ship number. Note that because we are adding -A to the value, we have to wrap the value in “ “ to denote that we are now using a string.

registry["James T Kirk"] = "1701-A"3. Print the contents of the registry. We can now see that James T Kirk has a new ship number.

Finally we need to delete Benjamin Sisko from the registry. It seems that he has gone “missing” while in the fire caves on Bajor. So we need to delete his entry from the registry. We’ll use the existing code, and add three new lines.

1. Add a print statement to show that we are deleting entries. This is entirely optional, but for the purpose of this example it clarifies that we are deleting entries from the dictionary.

print("Deleting Benjamin Sisko")2. Delete “Benjamin Sisko” from the registry. We don’t know who the new captain will be yet.

del registry["Benjamin Sisko"]3. Print the registry to confirm the deletion.

print(registry)4. Save and run the code.

Complete Code Listing: Updating and Deleting a Dictionary

registry = {}

registry["James T Kirk"] = 1701

registry["Hikaru Sulu"] = 2000

registry["Kathryn Janeway"] = 74656

registry["Ben Sisko"] = 74205

print(registry)

print("UPDATES")

registry["Benjamin Sisko"] = registry["Ben Sisko"]

del registry["Ben Sisko"]

print(registry)

print("Kirk's new ship")

registry["James T Kirk"] = "1701-A"

print(registry)

print("Deleting Benjamin Sisko")

del registry["Benjamin Sisko"]

print(registry)Using a For Loop With Dictionaries

For loops are awesome. We can use them to iterate through an object, retrieving data as it goes. Lets use one with our existing code example to iterate through the names (keys) and print the name and ship number for each captain.

1. Create a for loop to iterate through the keys and values in the registry dictionary. This loop will iterate through all the items in the dictionary, saving the current key and value each time the loop iterates.

for keys, values in registry.items():2. Create a sentence that embeds the Captain’s name (keys) and the ship’s number / registry (values).

print("Captain", keys, "registry is", values)3. Save the code and click Run. You will see the name and ship number for each captain printed at the bottom of the Python shell.

Complete Code Listing: Using a For Loop With Dictionaries

registry = {}

registry["James T Kirk"] = 1701

registry["Hikaru Sulu"] = 2000

registry["Kathryn Janeway"] = 74656

registry["Ben Sisko"] = 74205

print(registry)

print("UPDATES")

registry["Benjamin Sisko"] = registry["Ben Sisko"]

del registry["Ben Sisko"]

print(registry)

print("Kirk's new ship")

registry["James T Kirk"] = "1701-A"

print(registry)

print("Deleting Benjamin Sisko")

del registry["Benjamin Sisko"]

print(registry)

for keys, values in registry.items():

print("Captain", keys, "registry is", values)Using Dictionaries in a Real World Project

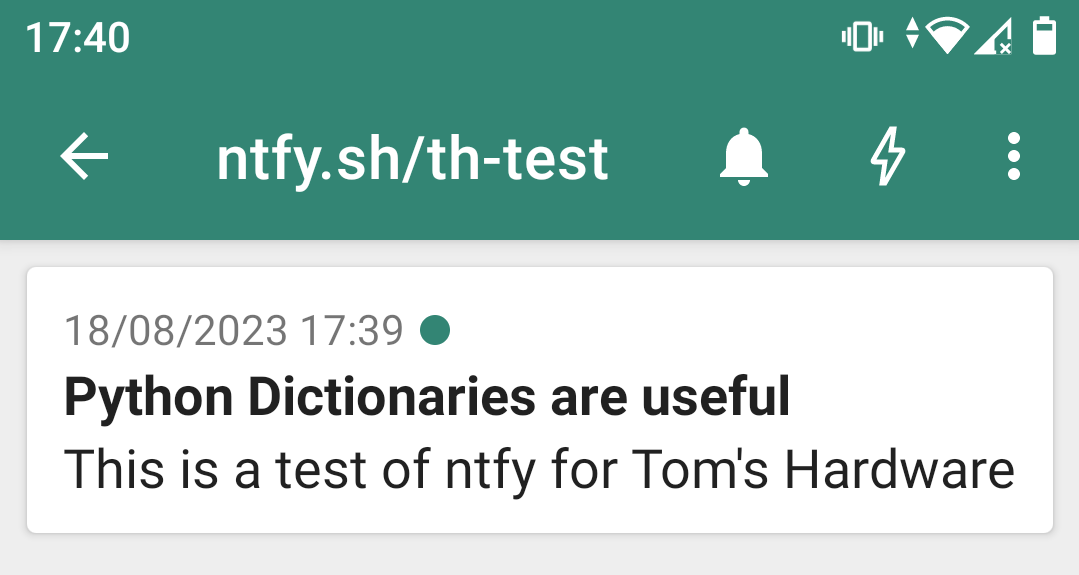

We’ve learnt the basics, now lets use a dictionary in a real world project. We’re going to use ntfy.sh, a service to send notifications to Android and iOS devices. The Python API for ntfy.sh is based on dictionaries. Best of all, there are no Python installation files as it uses Python’s requests module to handle sending messages to ntfy.sh.

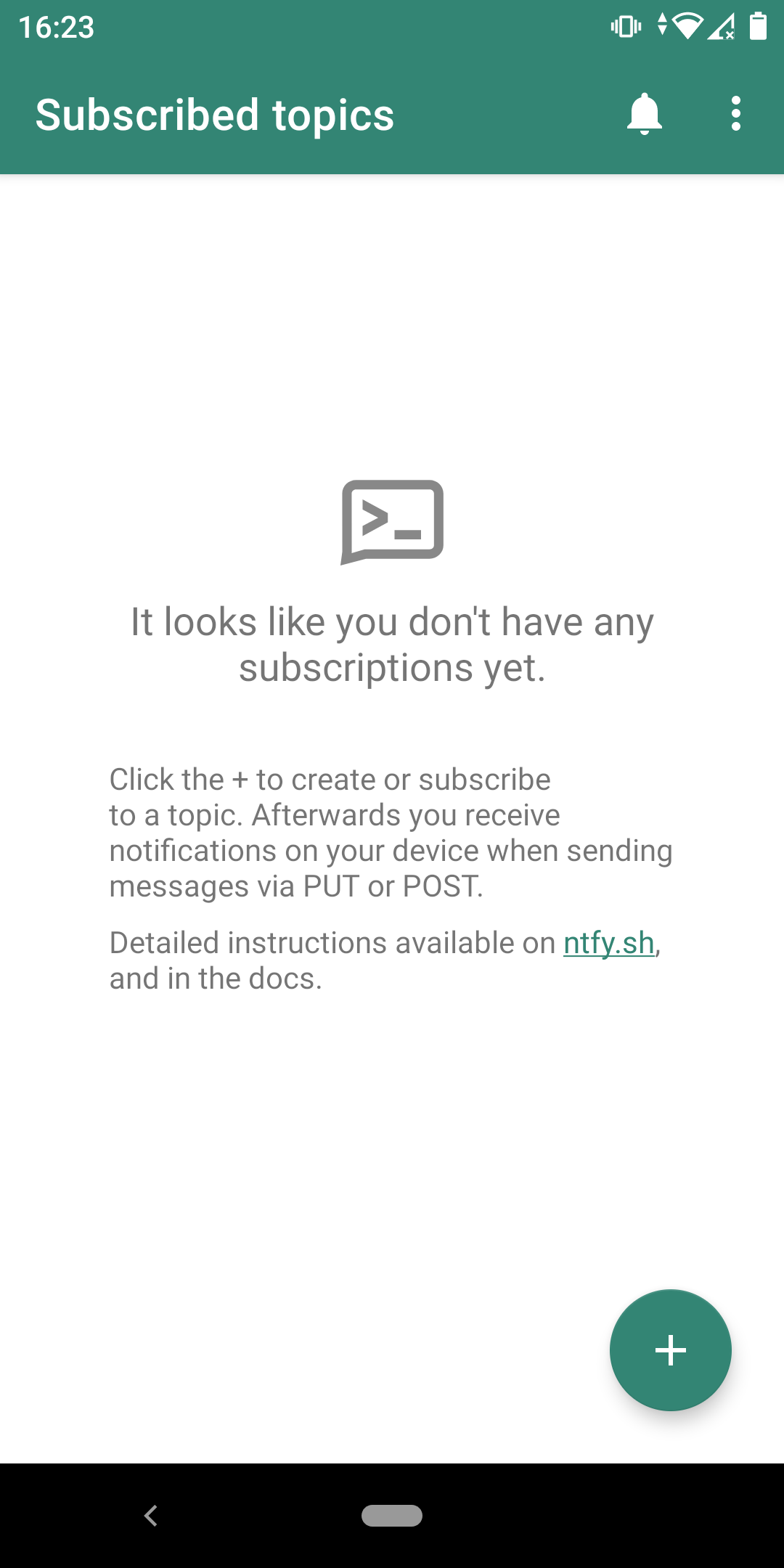

1. Install ntfy.sh for your Android / iOS device.

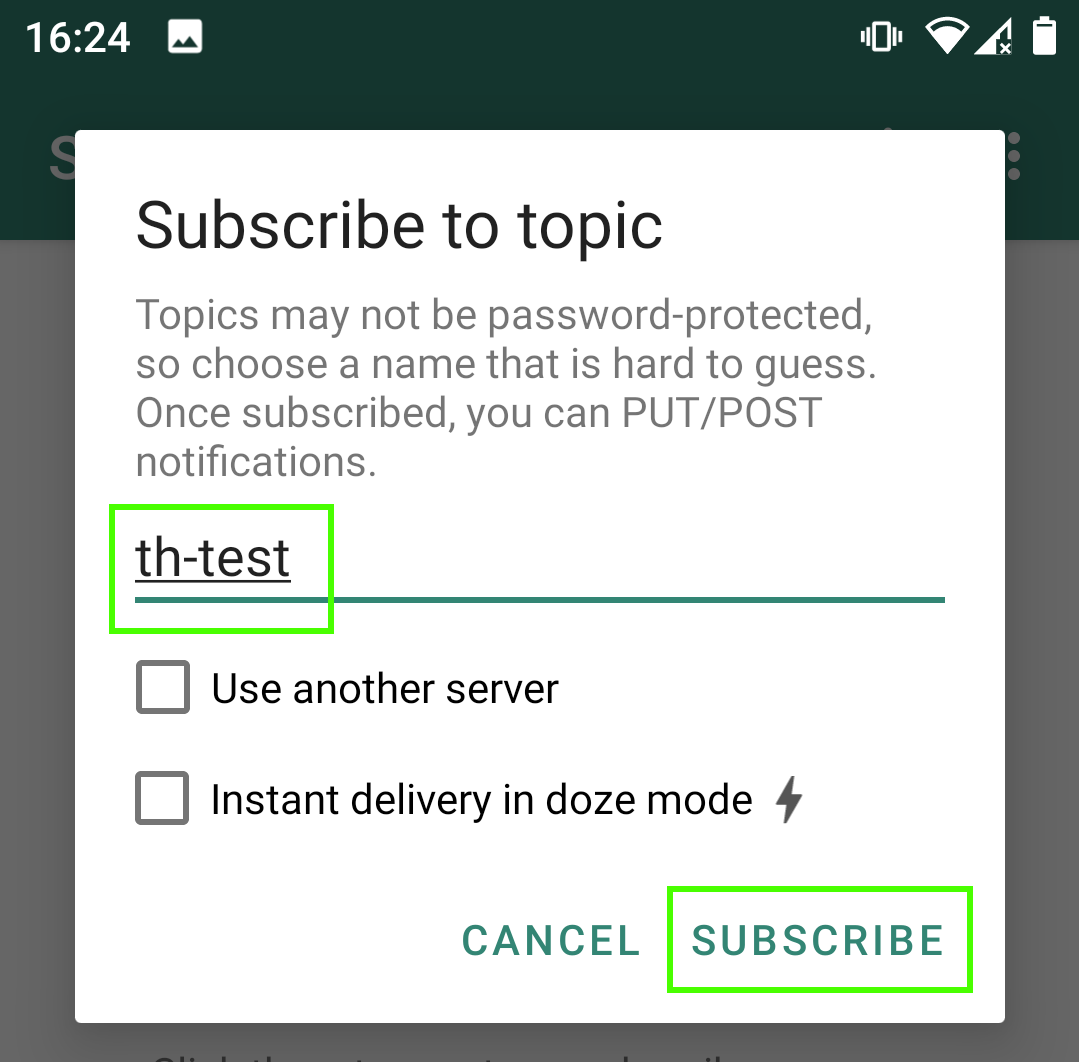

2. Open the app and click on + to create a new subscription.

3. Create a new topic and click Subscribe. We chose to use th-test. Create a topic that is personal to you. Also note that topics may not be password protected, so do not send sensitive data.

4. Leave the app open on your device.

Now our attention turns to our PC running Thonny.

5. Create a blank file.

6. Import the requests module. This is a module of pre-written Python code designed for sending and receiving network connections.

import requests7. Use requests to post a message to ntfy. Note that we need to specify the topic name, in our case https://ntfy.sh/th-test, as part of the function’s argument. The next argument, data is the text that the user will see. But our interest is in “headers” as this is a dictionary which can contain multiple entries. Right now it contains a title for the notification.

requests.post("https://ntfy.sh/th-test",

data="This is a test of ntfy for Tom's Hardware",

headers={ "Title": "Python Dictionaries are useful" })8. Save the code as dictionary-ntfy.py and click Run. This will send the message to ntfy’s servers and from there the notification will appear on your device.

Complete Code Listing: Real World Project

import requests

requests.post("https://ntfy.sh/th-test",

data="This is a test of ntfy for Tom's Hardware",

headers={ "Title": "Python Dictionaries are useful" })An Advanced Real World Dictionary Project

Lets create a more advanced project, one that uses a dictionary to store multiple items. We’re going to reuse the code from before, but tweak it to meet our needs.

1. Our import and requests line remain the same.

import requests

requests.post("https://ntfy.sh/th-test",2. Open and read a file into memory. This is the data that is sent in the notification. In this case we start with an image that is in the same directory as our code. If the image is in a different location on your machine, specify the full path to the file.

data=open("yoga.jpg", 'rb'),3. Create a dictionary called “headers”. This forms the information that is sent in the notification.

headers={4. Inside the headers dictionary, specify the following keys and values.

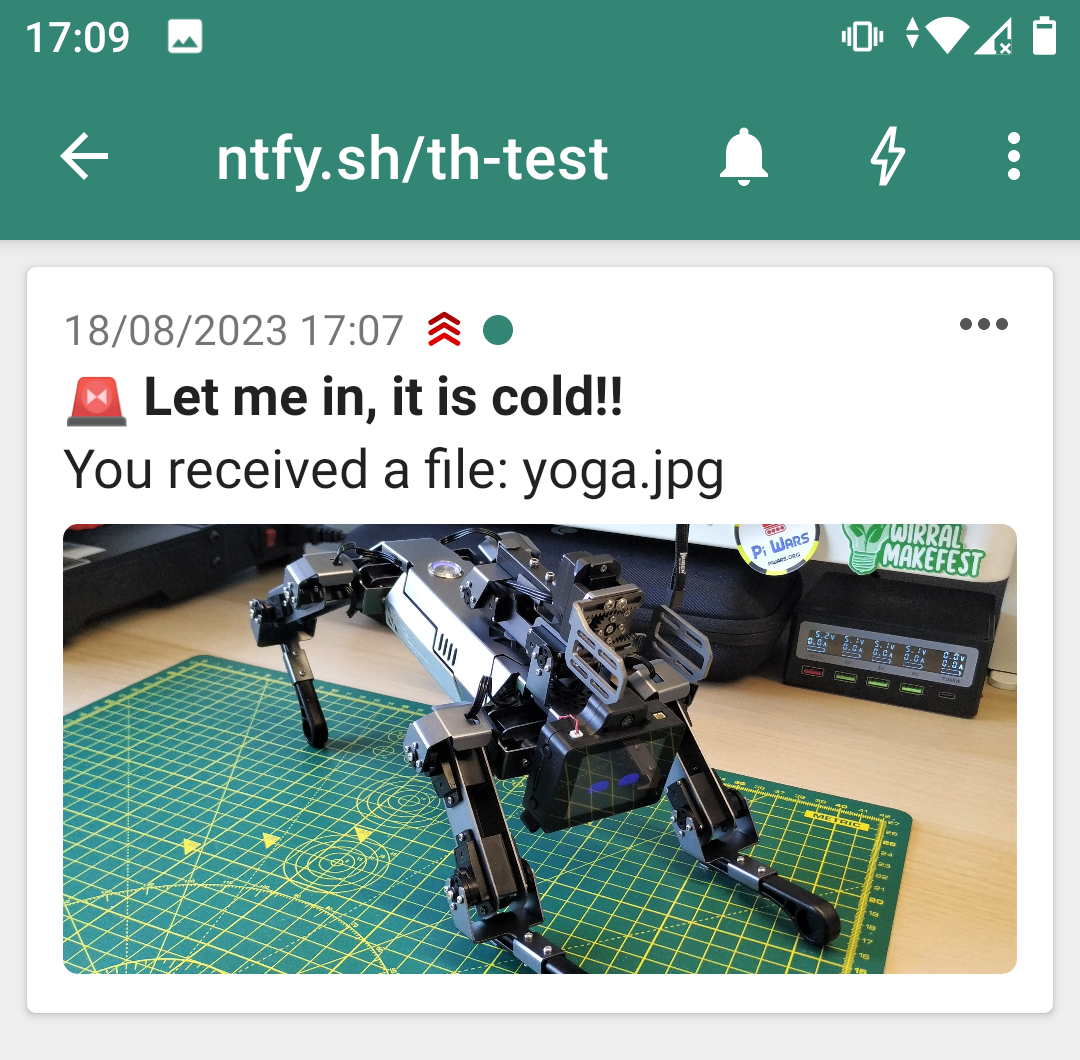

Priority 5 messages are urgent, the highest priority and they will set your phone to vibrate / ring continuously until they are answered.

Tags: These are emojis and tags used to add icons and extra data to a notification. If the tag has an emoji, then you will see it.

Title: The top title, in bold for the notification.

Click: When you click on the notification, it will open the web page.

Filename: The name of the file that is being sent.

"Priority": "5",

"Tags": "rotating_light",

"Title": "Let me in, it is cold!!",

"Click": "https://www.tomshardware.com/reviews/elecfreaks-cm4-xgo",

"Filename": "yoga.jpg"

})5. Save the code and click Run. Now look at your device and you will see a notification showing our custom message.

Complete Code Listing: Advanced Project

import requests

requests.post("https://ntfy.sh/th-test",

data=open("yoga.jpg", 'rb'),

headers={

"Priority": "5",

"Tags": "rotating_light",

"Title": "Let me in, it is cold!!",

"Click": "https://www.tomshardware.com/reviews/elecfreaks-cm4-xgo",

"Filename": "yoga.jpg"

})