The writer and translator who won the 2022 International Booker Prize talk about their relationship as interpreters of words and feelings, and about the alchemy of translation itself.

This essay is part of a series called The Big Ideas, in which writers respond to a single question: Who do you think you are? You can read more by visiting The Big Ideas series page.

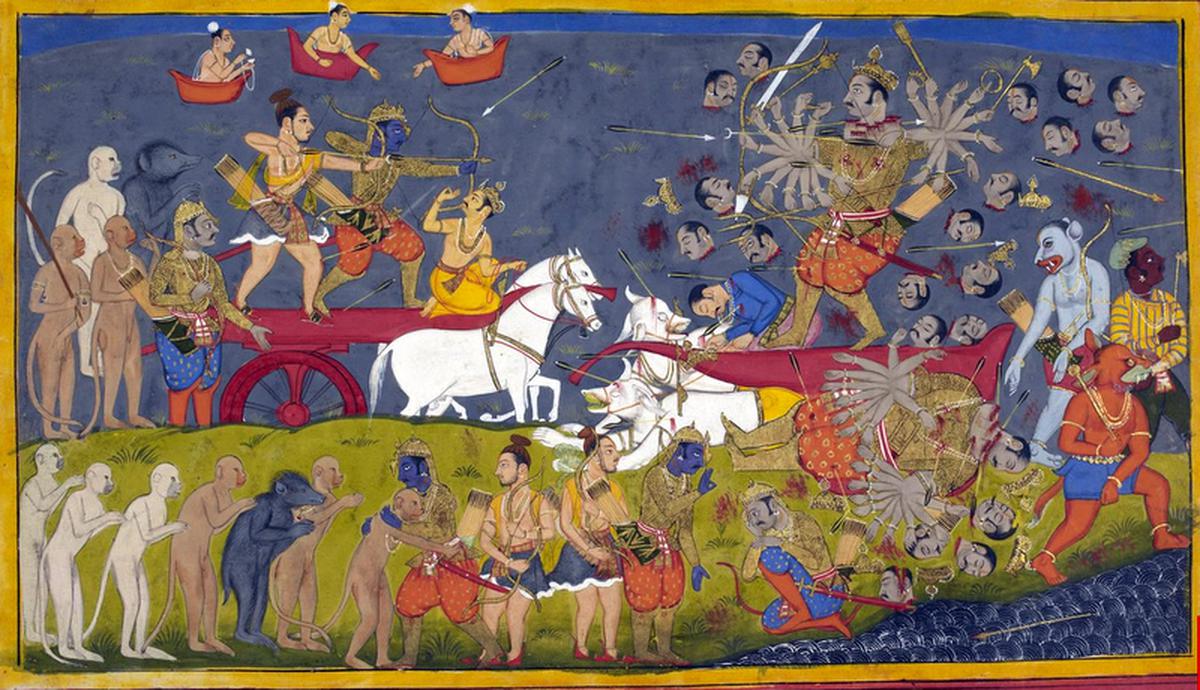

Our book, “Tomb of Sand,” is a translation by one of us, Daisy, of the Hindi novel written by the other, Geetanjali. The original novel, “Ret Samadhi,” was eight years in the making, and the translation another two and a half. The novel deals with the absurdity of boundaries — between people, genders, countries — but also between languages. With that theme as the backdrop, it stands to reason that in a translation, the border between writer and translator, between Hindi and English, is, at best, porous. After all, our first rule of translation is that those boundaries must dissolve.

Earlier this year, we were onstage at the Kolkata Literary Meet with last year’s English-language Booker winner, Shehan Karunatilaka. The moderator accidentally referred to the three of us as “both of you,” and Geetanjali quipped that she was glad he understood that the two of us were one.

What follows is a series of meditations on our state of being two in one, or, as we like to joke, “both of the one of us.”

On whom we are as writer and translator

Geetanjali Shree: Every writer is necessarily a translator. She articulates — translates into words — that inchoate, amorphous pre-word which jostles within her for expression. The translator, similarly, is also a writer. During our collaboration, I, the writer, tried to become the other — Daisy, the translator. I imagined her, and in that imagining I tried to be the process that made one text into the other. Then I could recreate, or reimagine, the process, learning more about both of us. At times our two identities merged in some kind of erosion of egos, but not fully — never fully! We always made it somewhere worthwhile. The writer, a translator, and the translator, a writer.

I remember an exchange I once witnessed, a mix of languages, feelings and the nonverbal, rendered here into English. A man saw his friend some distance away and called out in enthusiasm, raising his hand in greeting: “How are you, I hope?” The friend replied, expressing his not-so-good state in an unhappy gesture: “Somewhat, I think.” It is funny but profound, and illustrates our endeavor, where words in their literal meaning are only a part of the show.

Daisy Rockwell: We think of translation as a set of binaries — a journey between two texts, two languages, two writers, two places — but in actuality it is a continuum between these points. Loss is the immediate outcome, and discovery occurs over the long term. Where does Geetanjali stop, and where do I begin? Are we one author, or two?

On the act of translation

DR: The translator is a ventriloquist throwing a voice, but the voice is not her own. The translator is a medium receiving transmissions, but the transmissions come from another person whom she must become and write as.

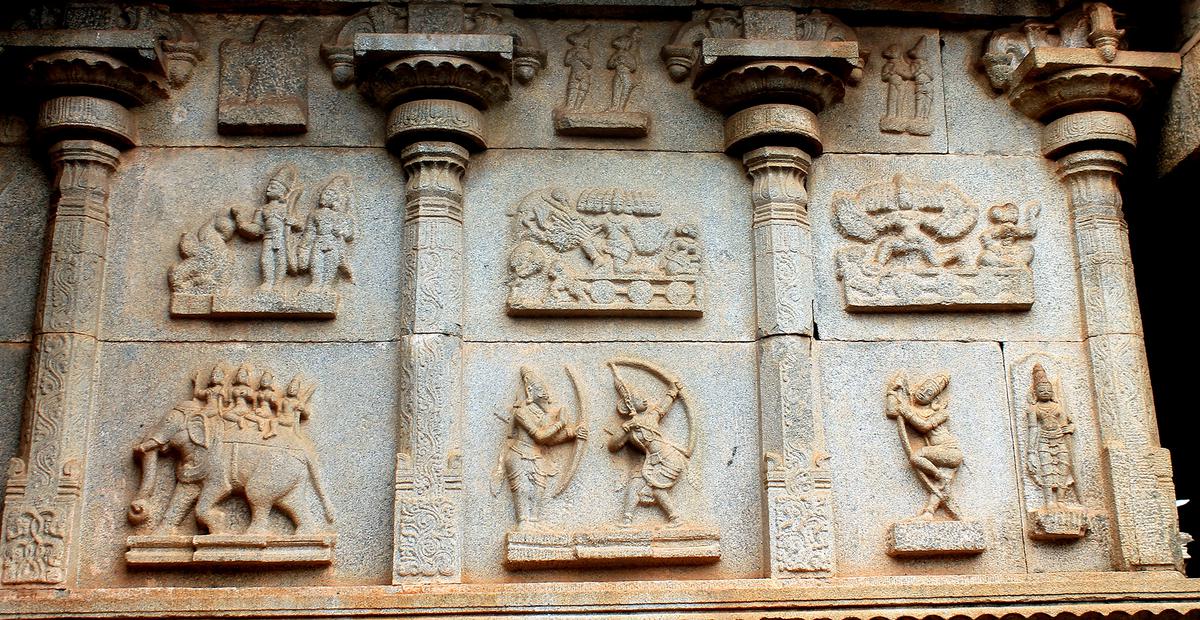

GS: Each of us became the other, but the definition of the other was always elusive. And we sometimes reveled in the game by deliberately eluding one another. A deity in a temple is inert clay until devotion and passion enliven it. When that deity moves to another temple it is reinfused with energy and becomes something else, even if its form remains the same.

DR: What of the original is truly lost in translation? Everything. All of it. Translation is what happens next.

GS: Yes, rhetorically or philosophically speaking, everything is lost. Every articulation is a new translation. And where am I in all of this? Constantly needing to inhabit new shapes emerging in the text, constantly becoming another voice and being, another character in the novel — the crow, the door, the road! I write, and then Daisy and I write vis-à-vis each other, trying to become each other, so we can draw each other out, respectfully, lovingly, admiringly.

On the life of a text after printing

GS: A translation is always in process. A conversation. Writing is translation and vice versa. Both of us are interested not just in words and their meanings, but also in catching the nonverbal and articulating that. And we are forever incomplete as we simultaneously pursue some elusive original and constantly move away from it. I, as a writer, am forever trying to give word-shape to a pluralistic, polyphonic, messy world emerging from the storehouse within me and around me, made up of things I cannot list in their entirety — things like memory; imagination; cultural, historical, philosophical heritage; and more.

DR: The ink has dried, the deed is done, the book lives in the world. It seems the death of the author and of the translator, and yet the process continues. The moment we have a chance, our debates continue. Does “tomb” belong in the title? How can you bury the complexity and depth of the Hindi word “samadhi” within the text? What about this? And what about that? The conversations continue outside the printed book, because translation is the gray area between two texts and two people.

Geetanjali Shree, a writer, and Daisy Rockwell, a translator, won the 2022 International Booker Prize for their novel “Tomb of Sand.”

COMMents