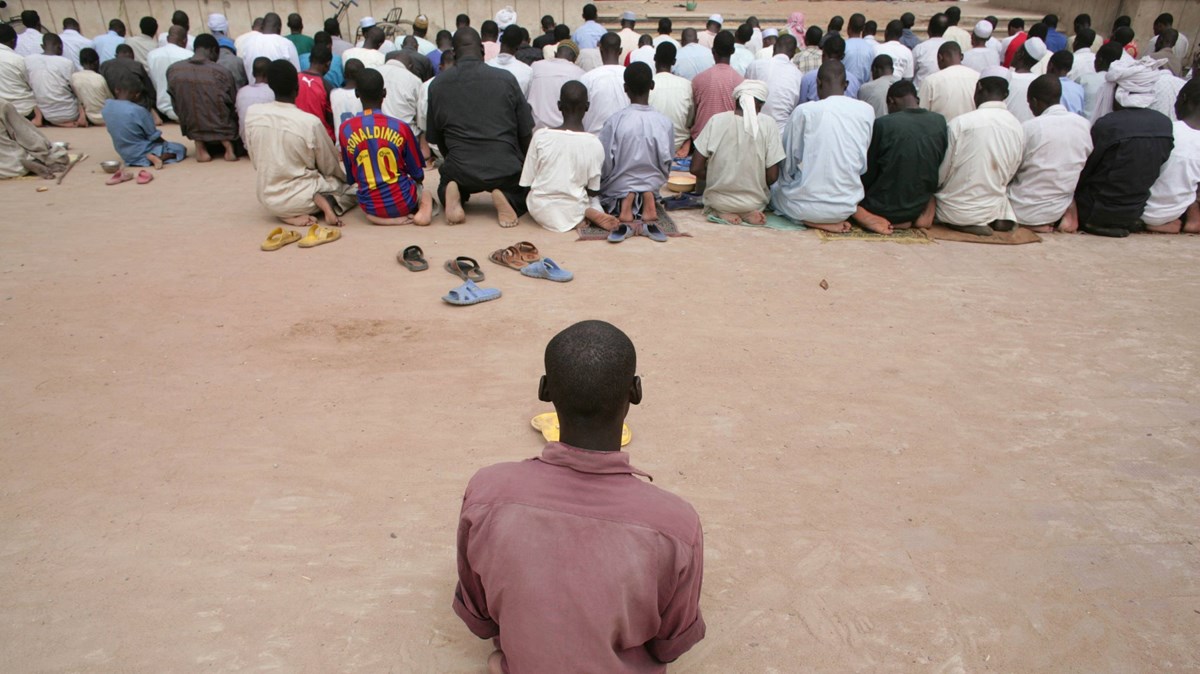

The Bible translation ministry unfoldingWord has engaged churches across countries and cultures, but a recent project in Chad brought a new dynamic to their work: The majority of the translators were Muslim.

“We can’t take credit for having thought this up or made this strategy,” said Eric Steggerda, field operations manager for unfoldingWord, which partnered in the Central African nation with the Church Growth Project of Chad (Projet Croissance des Eglises au Tchad), or PCET.

“God brought this together in a way that created an open door that neither one of us really expected would be as effective as it was,” Steggerda said. “What we learned was that this is actually a very effective way to bridge a gap with Muslims. Bible stories are understandable.”

Muslims make up a little over half the population in Chad, and Arabic and French are the two official languages, though most people speak a variant called Chadian Arabic.

PCET identified 10 minority languages they wanted to translate and held informational workshops to recruit participants for the translation projects.

A Chadian evangelical involved with PCET—who asked that his name be withheld due to fear of violence in response to the work in Muslim communities—told CT that many initially attended the translation workshop because they were interested in the pay.

But Christians noticed that Muslims quickly latched on to the projects for reasons beyond the financial incentive. PCET and unfoldingWord were clear that the materials for translation would be Christian, but Muslim participants saw some of the stories, such as those about Abraham, as part of their religion, too.

The Chadian communities that lack Christian materials in minority languages are unlikely to have the Qur’an in their local language either, according to Steggerda.

When working with language groups with few believers or new believers, unfoldingWord recommends starting with a set of about 50 stories that take translators through the Bible to build a solid understanding of God’s Word before translating Scripture passages themselves.

Many of those stories the Qur’an narrates differently, such as the creation account, or doesn’t include at all, such as the parable of the Good Samaritan. As the Muslim translators worked through the New Testament parable, Steggerda noticed that they were particularly eager to discuss the questions that went along with it.

Another reason Muslims were interested in translating Christian material was how the project affirmed the significance of their languages.

“Many of these languages are struggling for importance in the world, as it were. There’s not much that’s actually in their mother tongue, so they rejoice when they find things that are, because it really speaks to them of the importance of their language,” Steggerda said. “Of course, anything in the mother tongue resonates in the heart better than other languages, so they’re very receptive to the idea of the Bible stories, for example, translated into their mother tongue.”

A full Bible translation for Chadian Arabic, the language spoken by the majority in the country, was completed in 2019, with copies delivered to three locations in Chad by Mission Aviation Fellowship in 2021. There are more than 100 local dialects and languages, and in rural areas, people are less likely to speak or read in French, one of the official languages.

The question that arises from involving non-Christians in translation projects, especially those who don’t have degrees or expertise in translation work, is whether the translations will be linguistically and theologically sound.

UnfoldingWord focuses on church-based translation and believes non-Christians can help develop quality translations—while also learning about Scripture themselves. The training process has translators start with easier Bible stories to learn the basics and then move on to key passages before working on entire books of the Bible, with additional training and direction along the way.

Translations are done in teams, so each individual’s translation is checked by another group member and then by the group as a whole. Even with these processes in place, the trainers noticed that translators sometimes struggled with stories that clearly contradict Islamic doctrine. In Chad, PCET brought in pastors to check each group’s translations to guard against theological errors.

The translations are also shared in each community to glean feedback in specific contexts and as a way to proclaim the gospel.

The translation project in Chad started in 2018 but was slowed amid recent civil unrest, including the assassination of the Chadian president in 2021. As PCET continues to translate and share the new materials, leaders say they have seen God reach people through the project. Two of the Muslim translators have converted to Christianity through the translation process. People in unreached communities have turned to Christ as well, including some Muslim leaders.

In one area, the local team met with several fundamentalist imams who were skeptical about the project at first. After seeing the stories in their language, the imams let the team present them to the community at large. They urged the team to come back and continue presenting whatever translated materials they could.

In another village, Steggerda recounted, the chief was very sick when the team visited. They prayed for him to recover in the name of Jesus, and he was miraculously healed. The man committed his life to Christ and urged his entire village to be receptive to the translated materials and consider what the team had to say.

PCET supports the converts in these villages after the translation projects are complete.

“There’s a 50-person missionary network now established through this organization [PCET] that’s spread out and was assigned to these different language groups,” Steggerda said. “When a convert is made in one of these villages through the translation testing process, they are turned over to the associated missionary and sponsoring church for discipleship.”

In one Muslim community, where previous missionary efforts had failed, PCET leaders wanted to try again with the new materials translated into their local language, the Chadian leader told CT.

“We just followed the voice of the Holy Spirit and went to the community, with the elders and the leaders. We projected the videos and audio [of the translations], and the result we obtained there was very great,” he said. “Immediately after we left, the missionary that was posted there planted churches, and he baptized over 10 people in December.”

“People are getting enthusiastic about hearing the gospel of Christ for the first time in their own language.”

One reason these translation projects have been such effective evangelistic tools is that they let the unreached see that the gospel isn’t just for those in the West.

“People have a lot of assumptions toward Christianity. To them, Christianity is a Western product,” the Chadian leader explained. “When they can listen to Word of God in their own language, that changes the narrative.”

In Chad, the next phase of translation features sets of Scripture passages that help build theological knowledge. Though the makeup of the translation teams is ultimately left to local partners, unfoldingWord recommends using believers from the second phase onward.

UnfoldingWord’s approach contrasts with the establish model of Bible translation, where highly educated translators are deployed to learn a language and then create a new translation. The organization’s president, David Reeves, said both approaches are needed to continue to reach all peoples of the earth.

“God has blessed and needs to continue to bless [the established model], because we can’t finish this without them finishing what they started,” Reeves said. “What the emerging model is doing is going into places that are some of the hardest left on the planet and mobilizing a much bigger workforce to be able to accomplish this [translation work].”

The PCET leader and his team know the truth of this firsthand, as they witness more unreached people hearing the gospel in their language for the first time.

“The Great Commission is the business of the Lord Jesus in partnership with the Holy Spirit. We sow the seed, and the Holy Spirit waters the seed,” he said. “We are praying we’ll see the first fruits of our labor.”

Adblock test (Why?)