[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Oshi No Ko Opening's Artist Releases Official English Cover & Translation Screen RantSunday, May 28, 2023

Saturday, May 27, 2023

Burnsville native who dreams in Bulgarian wins share of International Booker Prize - Star Tribune - Translation

When Angela Rodel studied linguistics at Yale University, she didn't know translating was a legitimate career. On Tuesday, she shared the prestigious International Booker Prize for translating "Time Shelter," by Georgi Gospodinov, from Bulgarian into English.

"We've had eight hours of interviews today. It's insane! But I'm not complaining," Rodel said by phone from London, where the Booker ceremony took place. She and Gospodinov share the roughly $62,000 prize for the best work in translation published in the United Kingdom.

The 1992 graduate of Burnsville High School studied Russian and German at Yale, partly because, "I was a dark, angsty teenager." But she had sparked to Russian in high school: "This was totally strange but I guess the winds of perestroika made it there because one of the French teachers started teaching Russian, too."

At Yale, Rodel joined a Slavic chorus after hearing the music and thinking, "I want my voice to sound like that."

She went to Bulgaria as a Fulbright scholar after Yale, then earned a master's degree in linguistics from UCLA. On a return visit to Bulgaria in 2004, "I decided to stay. My husband at the time was a musician and poet and Sofia is a really small town. We all knew each other, so I met all these writers. Someone would give me a poem or story and I would translate it, just for fun."

Almost by accident, she became a full-time translator, which she now balances with being executive director of the Bulgarian Fulbright Commission.

Rodel hopes the Booker recognition helps change the notion that translated works are "second-hand goods."

"There's a perception that it's somehow 'less than' because it wasn't originally in English. But there are brilliant, talented writers all over the world," said Rodel, who speaks Bulgarian at home with husband Viktor and daughter Kerana and often dreams in the language.

Her job is not line-by-line transcription but something more artful.

"You want the reader to have a similar emotional experience in the translation as they would in the original. You try to capture the atmosphere, the style of the work. So, if there's something experimental, there should be something experimental in the translation," Rodel said. "If there's a humorous novel, with plays on words, maybe you can't do the exact same pun in a given sentence but there may be an opportunity to do one a few sentences later that works in English."

The Bulgarian language presents challenges for an English translator, including different verb tenses and gendered nouns.

The Burnsville native has worked often with Gospodinov, who also lives in Sofia. When the two learned in March that "Time Shelter" made the 13-book longlist, she said, "We thought, 'This is amazing. A Bulgarian book has never even made the longlist, so this will be the end of that.'"

They won the whole thing at a ceremony that included actor Toby Stephens reading from "Time Shelter."

"The invitation said to 'dress smart,'" said Rodel, who nodded to the art of translation by pairing a cocktail dress with a Bulgarian folk-art necklace. "It all started at 6 but they didn't announce the award until 10, so we were all just dying."

Rodel is working on several projects, including a translation of a Bulgarian novel to be published in January. Meanwhile, she and daughter Kerana will visit Eagan in July for a family reunion and lots of time in Minnesota parks.

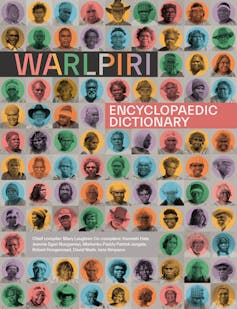

Six decades, 210 Warlpiri speakers and 11,000 words: how a groundbreaking First Nations dictionary was made - The Conversation - Dictionary

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people. The symbol † next to a personal name is a conventional respectful indicator that the person has died.

The first large dictionary of the Warlpiri language began in 1959 in Alice Springs, when Yuendumu man †Kenny Wayne Jungarrayi and others started teaching their language to a young American linguist, †Ken Hale.

Sixty years in the making, the Warlpiri Dictionary has been shortlisted for the 2023 Australian Book Industry Awards – a rarity for a dictionary.

Spoken in and around the Tanami Desert, Warlpiri is an Australian Aboriginal language used by around 3,000 adults and children as their everyday language.

Warlpiri artist Otto Sims Jungarrayi says:

In the old days when kardiya [non-Indigenous] people came, when they reached this continent, we had jukurrpa “law” here, not written on paper but true jukurrpa “law”, that the ancestors gave us. Now we put our language and our jukurrpa law on paper.

The dictionary and these materials represent the authority of elders, even if those elders are no longer present.

From the start of this project, Hale tape-recorded and transcribed many hours of Warlpiri people talking about language, country, kin and diverse aspects of traditional life.

The Warlpiri people he recorded came from different parts of Warlpiri country, speaking their own distinctive varieties of the language. From this material, Hale hand-wrote the words and meanings on small slips of paper that could be sorted in different ways.

Read more: Friday essay: my belly is angry, my throat is in love — how body parts express emotions in Indigenous languages

Making a dictionary

Bilingual education was introduced in Northern Territory schools in the 1970s. It meant the Warlpiri communities needed a common spelling system.

In the early 1970s, at Lajamanu community, Warlpiri men †Maurice Luther Jupurrurla and †Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala worked with linguist †Lothar Jagst to develop that spelling system. It was adopted in the new bilingual schools.

Dictionary work became a focus for the new linguist position at Yuendumu School, first filled in 1975 by the dictionary’s chief compiler, Mary Laughren. She worked closely in the school with dictionary co-compiler †Jeannie Egan Nungarrayi.

Over the next four decades, in a type of early crowd-sourcing, more than 210 Warlpiri speakers from different Warlpiri communities worked on and off with Laughren and others. They found words (ultimately 11,000 plus), decided how to spell them, translated them into English, showed how they can be used in Warlpiri sentences, and provided the social, cultural and biological information that makes this a truly encyclopaedic dictionary.

Co-compiler †Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala took on a mission to preserve the meanings of conceptually difficult and older words by writing definitions directly in Warlpiri. The 4,000 complex definitions in Warlpiri provide Warlpiri perspectives on the most important characteristics of each concept.

For example, in these two entries, both defined by †Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala:

Kukuju-mardarni is like when a person is happy or is sitting on their own feeling satisfied, or is nodding off to sleep, or is smiling – a man or a woman feeling happy about something like a lover or about their spouse whom they desire or because their lover has sent them a message.

Kukuju-mardarni, ngulaji yangkakujaka yapa wardinyi manu yangka nyinami kurntakurntakarra manu yukukiri wantinja-karra manu yinkakarra karnta manu wati yangka wardinyi nyiya-rlanguku marda waninja-warnuku manu marda kali-nyanuku kujaka yangka wardu-pinyi manu marda yangka kujakarla jaru yilyamirni waninja-warnurlu.

And:

Jalangu is a day which is not tomorrow or not yesterday. It is today. It is the time of daylight that is now.

Jalangu, ngulaji yangka parra jukurra-wangu manu pirrarni-wangu, jalanguju. Yangka parra rdili kujaka karrimi jalanguju.

Then, there was the laborious task of checking the draft dictionary entries.

Computer scientists assisted with data management and experimented with an electronic display, called Kirrkirr. Kirrkirr users can type in a word and see a visual display of meanings connected to that word (for example, words with a similar meaning, or the opposite meaning). They can also hear it pronounced, and see examples of how the word is used in Warlpiri.

Experts (among them anthropologists, Bible translators, botanists and zoologists) helped to identify plants, animals and more.

And artists, including Jenny Taylor and Jenny Green, provided images they had created for the Institute for Aboriginal Development Press Picture Dictionary series and other publications.

Passing on Warlpiri language

Warlpiri people have been working to pass on their language, to ensure their children and grandchildren can speak it.

Tess Ross Napaljarri began working as a teaching assistant 50 years ago, setting up the Yuendumu bilingual education program. She has described how she learned to read and write Warlpiri. “We became partners with the teachers in how to teach the Warlpiri children,” she says.

The children were learning their first language, Warlpiri, and second language, English, “and they were really smart on both languages”. The commitment of Warlpiri people to bilingual education has been – and continues to be – enormous. Since 2005, they have dedicated royalty money through the Warlpiri Education and Training Trust into supporting this work.

Warlpiri want Warlpiri children to be able to speak for themselves in a meaningful way – in both English and Warlpiri. Today, many Warlpiri now live away from Warlpiri country.

Tess’s niece, Bess Price Nungarrayi, is now assistant principal at Yipirinya School, on Arrernte country in Alice Springs. With more limited opportunities for hearing Warlpiri, Bess says the dictionary will be very useful in strengthening children’s Warlpiri.

This bilingual dictionary has many audiences. Warlpiri people enriching their knowledge of their language, Warlpiri and non-Warlpiri teachers preparing learning materials, Ranger groups studying eco-systems on Warlpiri country. And anyone wanting to learn about Warlpiri language, history, natural history knowledge and culture.

It can help Warlpiri speakers translate complex Warlpiri words into English, and it’s also an important tool for outsiders to learn Warlpiri – something Warlpiri people have long encouraged.

Read more: Friday essay: we are the voice – why we need more Indigenous editors

Future generations

Ormay Gallagher Nangala, a Warlpiri educator at the Bilingual Resources Development Unit, says:

Junga jintajinta-manulu nyurruwarnu-patu-wiyi ngulalpalu nyinaja, purlkapurlka wurlkumanu. And ngulajangkaju-ngalpa manurra, young people ka wangka school-rla karnalu warrki-jarri ngulalku, ngulangkalu jintajinta-manu and jungarlupa ngurrju-manu nyampu naa dictionary. Kurdu-kurdurlulu ngula nyanyi yangka.

The dictionary makers brought together information and intentions from the elders who have now passed away, the people who have been working in education for many years, and the future generations who will continue to learn Warlpiri.

This article was written with the collaboration of senior Warlpiri women Ormay Gallagher Nangala and Tess Ross Napaljarri.

Translation Of What Sami Zayn Said At WWE Night Of Champions – TJR Wrestling - TJR Wrestling - Translation

Sami Zayn delivered a promo in Arabic prior to the main event of WWE Night of Champions and there is a translation of what he said.

The main event of WWE Night of Champions in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia saw Sami Zayn & Kevin Owens defend the Undisputed WWE Tag Team Titles against The Bloodline’s Roman Reigns & Solo Sikoa.

Prior to the match, the “Wise Man” Paul Heyman took the microphone from ring announcer Paul Heyman and did a special introduction for Roman and Solo.

As a reply to Paul Heyman, Sami Zayn took the microphone and did his own introduction for the match. Since Zayn is a Syrian who knows how to speak Arabic, he decided to speak in Arabic to the Saudi Arabian crowd that speaks the same language as him.

With thanks to @naifsedge on Twitter, we have a translation of what Zayn said.

“Calm down. Calm down. Calm down. Pray to the prophet. We’re in an Arab country. We have an Arab champion. We’re gonna do this in Arabic. Introducing the prizefighter. (Now in English) Kevin Owens and Sami Zayn.”

When the bell rang, the two teams would have a memorable match that included a lot of chaos, especially after the original referee was knocked down during the match.

The Usos made their way down to the ring, they were trying to help Reigns & Sikoa win, but Reigns wasn’t happy about it, especially after The Usos hit a double superkick on their brother Solo. After being berated by Reigns, Jimmy Uso superkicked The Tribal Chief twice and the crowd was cheering even though they were shocked by it.

Sami Zayn would end up getting the win for his team after he hit a Helluva Kick on Solo for the pinfall win. Zayn & Owens remain the Undisputed WWE Tag Team Champions while Roman Reigns suffered a rare loss even though it was Solo taking the pin.

African American English Dictionary gives first look at 10 words, including 'bussin' and 'old school' - theday.com - Dictionary

Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., host and executive producer of the PBS series "Finding Your Roots," takes part in a panel discussion during the 2019 Television Critics Association Summer Press Tour in Beverly Hills, Calif., on July 29, 2019. (Photo by Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP, File)

A dictionary comprised of words created or redefined by Black people released a list of 10 words that will appear when the book is published in March 2025.

Topping the list is “bussin,” which is an adjective and a participle. The word, according to the definition revealed to The New York Times, can be used to describe a lively event or anything impressive. It can also describe tasty cuisine like “chitterlings,” a dish made from pig intestines.

The Oxford Dictionary of African American English will also include “old school,” or its variant “old skool” — characteristic of hip-hop or rap music born in New York City as the 1970s rolled into the ‘80s — as well as the term “kitchen,” which the book defines as “the hair at the nape of the neck.”

Harvard University African American history professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. is editing the endeavor, which he plans to grow to 1,000 definitions by its first printing.

“We are endlessly inventive with language, and we had to be,” Gates said of Black linguists. “We had to develop what literary scholars call double-voiced discourse.”

According to Gates, being able to communicate with slave owners, but also having a code only Black people would understand, was necessary for survival prior to emancipation. The 72-year-old scholar told the Times he’s working to verify the use of words his team is pulling from music lyrics, letters, periodicals and Black Twitter.

Gates recalls being a fan of dictionaries when he was an 8-year-old boy in the third grade. “I thought the dictionary was magical,” he said.

But finishing his daunting project will be no “cakewalk,” which the upcoming dictionary describes as “something that is considered easily done.” The etymology of “cakewalk” also harkens back to slavery when Black people competed for cake by performing stylized walks in pairs.

Also included on the list is “ grill ” (a dental overlay worn as jewelry), “pat” (a verb meaning to tap one’s foot) and “ring shout” (a ritual in which groups move in circles clapping and singing).

“Aunt Hagar’s children” — one of the book’s several terms with spiritual roots — refers to Black people collectively and is believed to be a noun inspired by Hagar in the Bible.

Rounding out the list of 10 words is “ Promised Land,” which is “a place perceived to be where enslaved people and, later, African Americans more generally, can find refuge and live in freedom.”

Friday, May 26, 2023

Barcelona loanee hits out at media for ‘incorrect translation’: “Call me if you need help” - Barca Universal - Translation

Barcelona defender Samuel Umtiti has hit out at media outlets after an incorrect translation of his interview, which many translated as he felt ‘imprisoned at Barça for four years’.

“To all journalists and newspapers… If you need help translating, you can call me next time. Depression equals depression, nothing to do with “prison” or jail. Thank you very much,” wrote the defender on his Instagram account (h/t Mundo Deportivo).

The exit-bound Barcelona defender recently spoke with Canal+ where he talked about his frustration at Barcelona, saying that the last four years were very difficult for him.

“I’m fine. I’ve spent four years in the Galleys, they’ve been hard four years, but now I’ve rediscovered my smile and the joy of playing football. They have given me this confidence here and I’ve been able to express myself as I did years ago,” said the defender.

“I don’t know if it was depression, but it was really complicated and difficult at all levels. I closed myself off a lot with my close people.”

“There were times in Barcelona when I didn’t want to leave the house. My friends told me to go out to change my mind, but I told them no, that I wanted to be alone. It was very complicated,” said the defender, who in no way described his Barcelona tenure as a prison.

Umtiti moved to Serie A outfit Lecce on loan at the beginning of the ongoing season. Ever since moving to Italy, the French defender has found a new life and is one of their top performers of the season.

As a result, the Serie A team is now exploring the possibility of signing the defender on a permanent transfer while there are other reports that he wants to move back to Olympique Lyon.

In any way, it is certain that Umtiti has no place in the current Barcelona team and despite his emotional comeback from mental trauma, he will be sold in the summer.

Thursday, May 25, 2023

Will The Oxford Dictionary Of African American English Help Address Language Appropriation? - HuffPost - Dictionary

Although African American Vernacular English is front and center in the way all of us communicate, it has always been regarded as slang. More recently, Black colloquial phrases have been wholly co-opted by certain subsets and make up what some more clueless people consider “internet-y” or “Gen Z speak.” Let’s be real: Describing your meal as “bussin” is not Twitter or TikTok slang. Anything remotely cool or flavorful in American culture came from Black people.

So it feels good to hear that Henry Louis Gates Jr. and a team of researchers from the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research have teamed up with the Oxford University Press to give Black English its long-overdue props. The Oxford Dictionary of African American English, set to be released in 2025, will define historically Black words and phrases and provide the more accurate origins of those words — reclaiming them, in a way.

The project involved extensive digging into music lyrics, letters, diary entries, magazines, and even slave narratives, according to The New York Times. In addition to pulling from historical sources, the team tapped into the best living sources it could find: Black women. The team included Anansa Benbow, producer of The Black Language Podcast, and Bianca Jenkins, whose graduate research included using language to identify fake Black Twitter accounts; they worked with linguists and lexicographers who have scoured hundreds of historical texts (and, of course, Black Twitter) to curate the dictionary, according to The New Yorker. The first volume will consist of 1,000 words and phrases that lay the foundation for an accessible resource that acknowledges the existence and impact of African American English.

While some of you may continue to pull up Urban Dictionary and Rap Genius for AAVE vocab (I feel the need to note that both were founded by white men), this dictionary will be a major anchor of accountability. It requires Oxford University Press to acknowledge the role white institutions and academia have played in policing and erasing African American English and expression, while also acknowledging that AAVE is a legitimate language.

The researchers for this project also found this style of English allows Black people to communicate in coded ways that keep us safe from white violence. During chattel slavery, anti-literacy laws prohibited enslaved Black people from reading and writing, which was a big factor in how the dialect was born.

The publisher’s decision to acknowledge these roots and tap on cultural experts to establish an official record is a huge step toward addressing generations of erasure. Up until recently, we’ve been encouraged to code-switch at school, in professional settings, and anywhere that is predominantly white. But now that it’s cool to exclaim “say less” in a Zoom meeting when enthusiastically co-signing an idea, it’s time that we have a governing body that reminds non-Black America that we are, and always have been, the linguistic drip.

To truly understand and respect AAVE, you must know its origin. All things said, once this Oxford Dictionary drops, I might start telling people I’m bilingual, cause honestly, “Who gon check me?”