[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Genius English Translations – TOMORROW X TOGETHER - Sugar Rush Ride (English Translation) GeniusFriday, January 27, 2023

Thursday, January 26, 2023

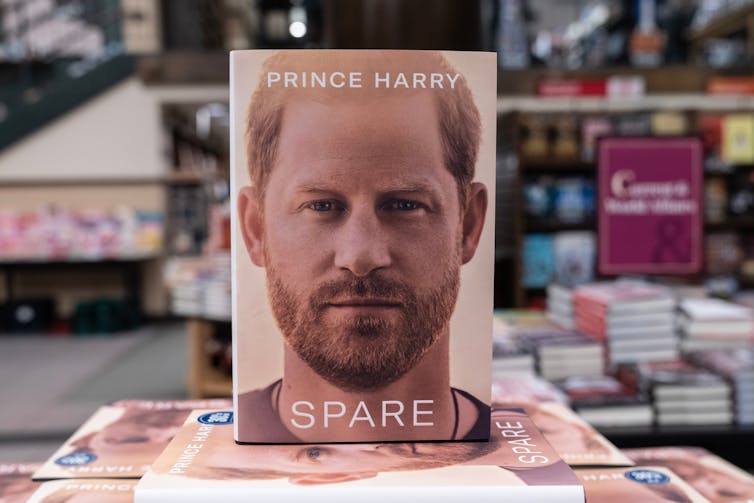

Prince Harry: early leaks came from a Spanish translation, causing confusion about what was really said - The Conversation Indonesia - Translation

Eight days before Prince Harry’s memoir Spare hit shelves elsewhere, copies went on sale prematurely in Spain.

Over the next few days the UK media, scrambled to acquire Spanish copies of the book, having been unable to get English versions for themselves. Their reporting on the story was initially based on these Spanish versions.

The fact that many of the quotes had been translated from English to Spanish and then back into English was barely acknowledged. Sometimes, this results in change, or different versions, as we see below. The book’s tagline is “His Words. His Story.” and part of the coverage centred around why it was important that these were Prince Harry’s own words. Yet what those words actually were, depended on where you read them.

His words?

One much quoted extract from Spare is Prince Harry’s account of how many members of the Taliban he had killed. He writes:

So, my number: twenty-five. It wasn’t a number that gave me any satisfaction. But neither was it a number that made me feel ashamed.

This was a focal point for early spoilers on the book and was quoted differently in different publications.

On Sky: “So my number: twenty-five. It was not something that filled me with satisfaction, but I was not ashamed either.”

In The Times: “So my number is 25. It’s not a number that fills me with satisfaction, but nor does it embarrass me.”

Neither of these translations is wrong. They show different ways of rendering the same idea – but the cumulative effect is important.

It was unclear whether early criticisms were responding to the published version or alternative translations. Those attacking the author for his stance may not in fact have been responding to “his words” at all.

A more detailed example comes in Prince Harry’s account – here taken from the book in English – of losing his virginity:

Inglorious episode, with an older woman. She liked horses, quite a lot, and treated me not unlike a young stallion. Quick ride, after which she’d smacked my rump and sent me off to graze. Among the many things about it that were wrong: It happened in a grassy field behind a busy pub.

Unsurprisingly, this was another of the most frequently quoted leaks. But again, the wording is not consistent. The Daily Mail quoted:

“… a humiliating episode with an older woman who liked macho horses and who treated me like a young stallion. I mounted her quickly, after which she spanked my ass and sent me away. One of my many mistakes was letting it happen in a field, just behind a very busy pub.”

There are some significant differences. Firstly, a shift in agency and responsibility: a “quick ride” is recast to position Harry as dominant (“I mounted her”), while “things that were wrong” become “my many mistakes”, suggesting self-accusation.

There is also awkwardness, in the term “macho horse” and in the reference to ass spanking: would the author who talks elsewhere about his “todger” also say “ass”?

The different word choices may be partly about different translators working on the text that appeared in different places. A translator collaborates in rewriting the author’s text, brings out its interest and value, reads carefully for hidden layers of meaning and confronts difficulties and inconsistencies.

Languages don’t map directly onto one another and there is often more than one way to translate a given word or phrase. What’s notable here is that the invisibility of the English to Spanish to English translation process leaves readers not understanding why there are different versions.

His story?

Translation theorists have talked about translation as a kind of “rewriting”. Recognising the translator as an active writing agent is key to exploring the ethical question of whose voice is heard in translated texts.

However, the participation of others in the telling doesn’t necessarily mean Spare is no longer Prince Harry’s story.

Storytelling is central to how we establish our identity, and it is social. We rely on communities to retell our stories and so, as the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre explains: “We are never more (and sometimes less) than co-authors of our own narrative.”

But how far can the ownership of Prince Harry’s narrative stretch when the words are no longer “his”? As we have seen, when fragments and differently translated snippets are all presented as “the text”, the resulting inconsistency undermines the authenticity of the story, and with it the agenda of the book.

The marketing for Spare and media appearances surrounding its publication have leaned heavily on a bid to “tell my own story” and resist “words being taken out of context”. The realities of translation show how difficult this is.

Kamen Rider Kuuga Manga's English Translation Under Fire for Errors - Gizmodo - Translation

Translating media from one language into another is always going to be a fraught process—from trying to retain a style and nuance between dialogue, to navigating fanbases that often perceive any kind of difference in localization as censorship. But there’s a difference between that, and what’s happened to Titan’s Kamen Rider Kuuga releases.

- Off

- English

Although the first two volumes of Stonebot and Titan Comics’ English release of Toshiki Inoue and Hitotsu Yokoshima’s Kamen Rider Kuuga manga—adapting the classic 2000 Kamen Rider series that revitalized the superhero franchise for the 21st century—have been available for a few months now, the series has come under fire this week after fans pointed out a consistent pattern of errors and awkward phrasing in the English translation of the manga. From clunky syntax to inconsistent name romanization, from awkward line breaks to printing errors cutting off art and dialogue, both volumes of Kuuga showcase a pattern of sloppiness that make them difficult to read at best.

But matters were made worse when the furor around the translation’s awkwardness revealed that Titan had been selling the Kuuga manga with an altogether different translation. Preview pages released last summer—including ones shared by io9 at the time—feature a translation that is not just different to the final release in terms of better sentence structure and phrasing, but in formatting and stylization too, utilizing different fonts and occupying more space in speech bubbles for dramatic effect, as well as stylized FX translations.

Today, Titan released a brief statement acknowledging fan concerns while also explaining the disparities between the previewed pages of both released volumes of the Kuuga manga—volumes 3-5 are currently available to pre-order—were the result of intents to get previews of the series out quickly.

“In April 2022, early draft pages (three pages for Volume 1 and four pages for Volume 2) were translated for marketing purposes, as we wanted to get the artwork out as soon as possible for the fans,” Titan’s statement reads in part. “These may still be circulating on the web. The actual translation for the printed books (approved by Titan and licensors) were worked on by two highly respected translators in the business.”

While this may explain the disparity between preview and final release, it doesn’t explain why Titan continued to use the separately translated preview pages in the run-up to, and after the release of, the first two volumes of Kamen Rider Kuuga. Tweets as recently as January 23, two days ago, continue to use the inaccurate preview images to advertise the comic, despite the fact that the worse translation was already in the hands of fans. Amazon’s U.S. store pages for Kamen Rider Kuuga volumes 1-2 also use the released translation as previews now, as opposed to the initial preview pages.

Kamen Rider has gained an international fanbase often in spite of itself across its long history, with much of the franchise—whether shows and movies, merchandise, or adapted material like manga and comics—still legally inaccessible to audiences outside of Japan. Although fits and starts have been made to bring the series to a wider audience in other countries, Kamen Rider is still an incredibly niche franchise, one supported by diehards who’ve put up with a lot in an attempt to ensure more people can legally enjoy the series they love.

But Rider fans shouldn’t have to put up with being hoodwinked in a manner such as this, and sold a sloppily translated product under the perceived onus of having to support it to prove a continued interest in the series beyond its home shores. If the difference in quality between fan-translated material and official releases is going to have such vast disparity, the companies Toei is working with to try and make Kamen Rider a mainstream superhero franchise outside of Japan are going to have to do much better to prove to the Rider fanbase that their access is going to do better for the series’ community than the work that community has been doing to sustain itself for decades beforehand.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.

Titan Will Fix Kamen Rider Kuuga Manga After Translation Controversy - Gizmodo - Translation

After days of fan concerns about the state of the Kamen Rider Kuuga manga’s English translation, publishers Titan Comics and StoneBot have announced plans to fix the litany of errors and disparities in future releases and re-prints.

- Off

- English

“We at Titan have been listening very carefully over the past few days to your feedback on the highly anticipated Kamen Rider Kuuga manga translation,” a new statement released on social media by Titan reads in part. “As a result, we wanted to let readers know that we are now actively resolving the issues that the community has raised for existing volumes.”

According to the statement, Titan plans to correct both the digital release and future printings of the first two volumes of Toshiki Inoue and Hitotsu Yokoshima’s Kamen Rider Kuuga manga, fixing “any identified art errors and textual inconsistencies.” Furthermore, the publisher claims that it will now implement “extra internal editorial processes” and “continue to work closely with our translators and Kamen Rider brand experts” in order to improve the accuracy and coherency of translations for future volumes.

Neither Titan nor StoneBot’s statements particularly dive further into the controversy around the originally released preview pages for the manga, which used a different—and stronger—English translation, or why Titan continued to promote the manga with those previews after the releases of volumes 1-2. StoneBot, the actual licensee for the Kuuga manga, alleges that the preview pages were translated by themselves with Argentinian sister publisher OVNI press, which publishes Kuuga in Spanish. Those English-language pages were created to match the stylization of the Spanish-language release, but “it was later decided to go on a different direction” for the actual book, in order to have it appear “similar to current manga localizations in the market.”

While there’s still plenty of questions around just why the first two volumes were released in the state they were, at the very least Titan’s new statement promises changes will be made in the wake of the Kamen Rider community’s criticisms of the release. Time will tell just how extensive those changes will be—hopefully enough to make Kuuga’s English translation a release worth supporting by a fandom eager to grow Kamen Rider’s appeal around the world, instead of one they’re asked to begrudgingly accept in the name of official support.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.

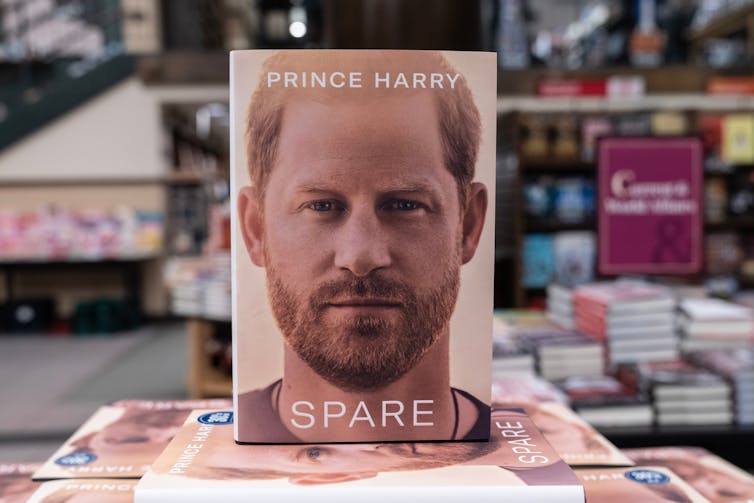

Prince Harry: early leaks came from a Spanish translation, causing confusion about what was really said - The Conversation Indonesia - Translation

Eight days before Prince Harry’s memoir Spare hit shelves elsewhere, copies went on sale prematurely in Spain.

Over the next few days the UK media, scrambled to acquire Spanish copies of the book, having been unable to get English versions for themselves. Their reporting on the story was initially based on these Spanish versions.

The fact that many of the quotes had been translated from English to Spanish and then back into English was barely acknowledged. Sometimes, this results in change, or different versions, as we see below. The book’s tagline is “His Words. His Story.” and part of the coverage centred around why it was important that these were Prince Harry’s own words. Yet what those words actually were, depended on where you read them.

His words?

One much quoted extract from Spare is Prince Harry’s account of how many members of the Taliban he had killed. He writes:

So, my number: twenty-five. It wasn’t a number that gave me any satisfaction. But neither was it a number that made me feel ashamed.

This was a focal point for early spoilers on the book and was quoted differently in different publications.

On Sky: “So my number: twenty-five. It was not something that filled me with satisfaction, but I was not ashamed either.”

In The Times: “So my number is 25. It’s not a number that fills me with satisfaction, but nor does it embarrass me.”

Neither of these translations is wrong. They show different ways of rendering the same idea – but the cumulative effect is important.

It was unclear whether early criticisms were responding to the published version or alternative translations. Those attacking the author for his stance may not in fact have been responding to “his words” at all.

A more detailed example comes in Prince Harry’s account – here taken from the book in English – of losing his virginity:

Inglorious episode, with an older woman. She liked horses, quite a lot, and treated me not unlike a young stallion. Quick ride, after which she’d smacked my rump and sent me off to graze. Among the many things about it that were wrong: It happened in a grassy field behind a busy pub.

Unsurprisingly, this was another of the most frequently quoted leaks. But again, the wording is not consistent. The Daily Mail quoted:

“… a humiliating episode with an older woman who liked macho horses and who treated me like a young stallion. I mounted her quickly, after which she spanked my ass and sent me away. One of my many mistakes was letting it happen in a field, just behind a very busy pub.”

There are some significant differences. Firstly, a shift in agency and responsibility: a “quick ride” is recast to position Harry as dominant (“I mounted her”), while “things that were wrong” become “my many mistakes”, suggesting self-accusation.

There is also awkwardness, in the term “macho horse” and in the reference to ass spanking: would the author who talks elsewhere about his “todger” also say “ass”?

The different word choices may be partly about different translators working on the text that appeared in different places. A translator collaborates in rewriting the author’s text, brings out its interest and value, reads carefully for hidden layers of meaning and confronts difficulties and inconsistencies.

Languages don’t map directly onto one another and there is often more than one way to translate a given word or phrase. What’s notable here is that the invisibility of the English to Spanish to English translation process leaves readers not understanding why there are different versions.

His story?

Translation theorists have talked about translation as a kind of “rewriting”. Recognising the translator as an active writing agent is key to exploring the ethical question of whose voice is heard in translated texts.

However, the participation of others in the telling doesn’t necessarily mean Spare is no longer Prince Harry’s story.

Storytelling is central to how we establish our identity, and it is social. We rely on communities to retell our stories and so, as the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre explains: “We are never more (and sometimes less) than co-authors of our own narrative.”

But how far can the ownership of Prince Harry’s narrative stretch when the words are no longer “his”? As we have seen, when fragments and differently translated snippets are all presented as “the text”, the resulting inconsistency undermines the authenticity of the story, and with it the agenda of the book.

The marketing for Spare and media appearances surrounding its publication have leaned heavily on a bid to “tell my own story” and resist “words being taken out of context”. The realities of translation show how difficult this is.

ComForCare Recognized in Franchise Dictionary Magazine's Top 100 Game Changers for 2022 - Yahoo Finance - Dictionary

TROY, Mich., Jan. 26, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- Franchise Dictionary Magazine recognizes ComForCare, a franchised provider of in-home caregiving services, as one of the top 100 Game Changers of 2022. This recognition highlights franchises that fill a niche, help the communities they are a part of, and provide opportunities for aspiring business owners.

"It's an honor to once again be included on the Top 100 Game Changers list," said J.J. Sorrenti, CEO of Best Life Brands, parent company to ComForCare/At Your Side. "Our entire franchise network has been working hard to bring in-home care to communities all across North America. This recognition underscores the importance of serving an aging population with compassion and integrity. We look forward to reaching even more growth milestones in 2023."

ComForCare has been providing quality services to the aging population for over 20 years. Driven by compassion and the desire to bring peace of mind to seniors and their families, ComForCare places caregivers in the homes of older adults who want to be independent, or provides respite care for family caregivers.

Alesia Visconti, CEO of Franchise Dictionary Magazine says, "2022 was a year of rebuilding and success in the franchise community. A brand that earns the Top 100 Game Changers designation has gone the extra mile to improve people's lives and sets itself apart! We are THRILLED to recognize and showcase these 100+ fran-tastic brands that went above and beyond. Congrats to this year's Game Changers!"

The full list of the top 100 "Game Changers" can be found in the December issue of Franchise Dictionary Magazine.

To learn more about ComForCare franchising, visit https://ift.tt/CjqzFHB.

About ComForCare Home Care:

ComForCare is a premier franchised provider of in-home caregiving services with 270 independently-owned and operated locations in Canada and the U.S., helping older adults live independently in their own homes. ComForCare is committed to helping people live their best lives possible and offers special programs, including fall risk prevention, dementia care, meaningful activities, and Joyful Memories music. Founded in 1996, ComForCare was acquired by private equity firm The Riverside Company in 2017 and is now part of Best Life Brands, which has plans for continued expansion of service brands across the continuum of care. ComForCare has earned a ranking of 402 on the Entrepreneur Franchise 500 list. For more information, visit www.comforcare.com.

View original content to download multimedia:https://ift.tt/cJawZ31

SOURCE ComForCare Home Care

Merriam-Webster buys Wordle-style hit game Quordle - BBC - Dictionary

US dictionary publisher Merriam-Webster has acquired a hit Wordle-style game.

The original Wordle, created by Welsh software engineer Josh Wardle, challenges players to find a five-letter word in six guesses.

Quordle ups the ante, asking players to guess four five-letter words at once within nine attempts.

The New York Times acquired Wordle for a low seven-figure sum. While Heardle, a song-guessing game also inspired by Wordle, was bought by Spotify, in July.

"I'm delighted to announce that Quordle was acquired by Merriam-Webster! I can't think of a better home for this game," Quordle creator Freddie Meyer wrote.

Merriam-Webster president Greg Barlow told news website TechCrunch Quordle was a "favourite of Merriam-Webster editors".

Neither party has revealed the terms of the deal.

Reacted angrily

Some Wordle fans were unhappy with changes to the game following its 2022 sale and the New York Times has discovered even the apparently innocuous business of picking five-letter words can stir up controversy.

In the week the US Supreme Court decision overturning legal protections for abortion leaked, some users discovered the word they had to guess was "fetus" (spelled "foetus" in British English), before the papers switched the solution, saying they wanted Wordle to "remain distinct from the news".

Some Heardle fans also reacted angrily to changes and bugs following its sale to Spotify.

But Quordle fans may be happier with the change of ownership of their favourite app, reports suggest.

Some players had been annoyed by the frequency with which the app repeated words, Engadget wrote, adding: "With a dictionary company now in charge, here's hoping Quordle will freshen things up."