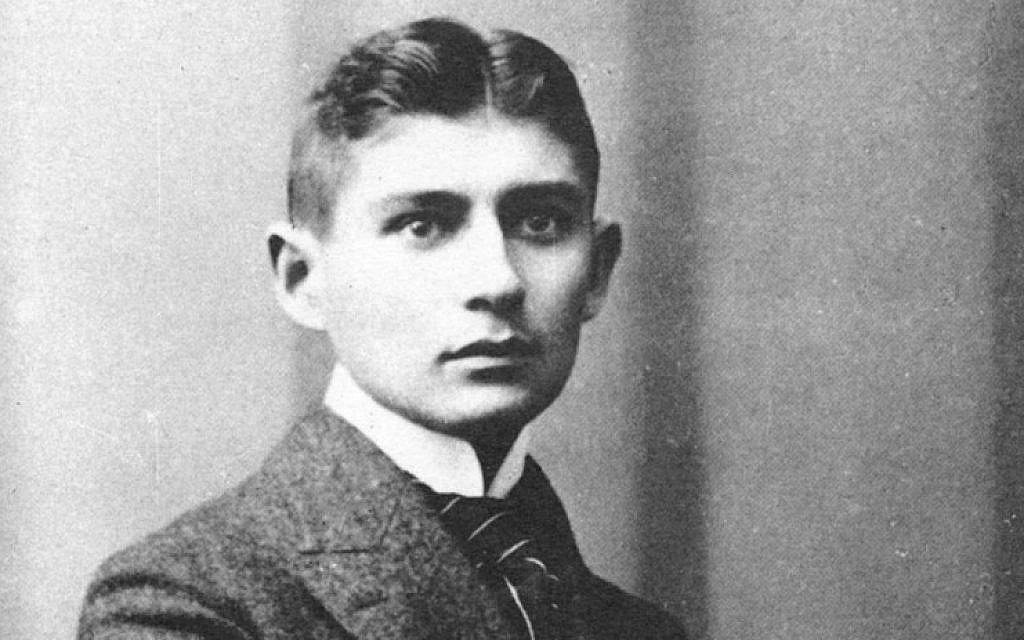

JTA — Franz Kafka was a devotee of Yiddish theater, fell in love with his Hebrew teacher and once encountered the owner of a brothel he frequented in synagogue on Yom Kippur.

The broad strokes of Kafka’s biography have long been known to historians, but a new English translation of the Czech author’s complete and unabridged diaries gives readers the fullest possible picture of his complex, contradictory relationship with Judaism.

For an author most famous for his depictions of loneliness, alienation and unyielding bureaucracy, Kafka often saw in Judaism an opportunity to forge a shared community.

“The beautiful strong separations in Judaism,” he praises at one point, in a disjointed style that is a hallmark of his diaries. “One gets space. One sees oneself better, one judges oneself better.”

Later, writing about a Yiddish play he found particularly moving, Kafka reflected on its depiction of “people who are Jews in an especially pure form, because they live only in the religion but live in it without effort, understanding or misery.” He was also involved with several local Zionist organizations, and toward the end of his life fell in love with Dora Diamant, the daughter of an Orthodox rabbi who taught him Hebrew (though she receives scant mention in the diaries).

“The Diaries of Franz Kafka,” translated by Ross Benjamin and out this week from Penguin Random House, collects every entry of the writer’s personal diaries covering the period from 1908 until 1923, the year before his death from tuberculosis at the age of 41.

Although versions of Kafka’s diaries had previously been published thanks to the efforts of his Jewish friend and literary executor Max Brod (with translation assistance from Hannah Arendt), they had been heavily doctored with many passages expunged, including some of what Kafka had written about his own understanding of Judaism. A German-language edition of the unabridged diaries was published in 1990.

The author of “The Metamorphosis,” “The Trial” and “The Castle” was raised by a non-observant father in Prague, and he hated the small amounts of Jewish culture he was exposed to at a young age, including his own bar mitzvah. In addition, the city’s largely assimilated German-speaking Jewish population tended to look down on poorer, Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews.

But Kafka’s diaries also reveal a growing fascination with Jewish culture in young adulthood, particularly around a traveling Yiddish theater troupe from Poland whom he saw perform nearly two dozen times. He developed a close relationship with the company’s lead actor, Jizchak Löwy, and would host recitation events where he’d give Löwy the opportunity to perform stories of Jewish life in Warsaw.

Kafka himself would even write and deliver an introduction to these performances in Yiddish. He also witnessed his own father harboring prejudices toward his new friend Löwy, saying, “My father about him: He who lies down in bed with dogs gets up with bugs.”

“The Metamorphosis” famously revolves around a man who inexplicably is transformed into a giant bug and is then rejected by his family. In his introduction, Benjamin notes, “Scholars have suggested that such tropes, prevalent as they were in the antisemitic culture in which Kafka reckoned with his own Jewishness, influenced the themes of his fiction.”

Some of Kafka’s more ambiguous comments about his Jewish brethren were previously removed by Brod, according to Benjamin’s introduction to the diaries.

At one point while hanging out with Löwy, Kafka invokes antisemitic stereotypes about Jewish uncleanliness: “My hair touched his when I leaned toward his head, I grew frightened due to at least the possibility of lice.” Benjamin notes: “Here Kafka confronts his own Western European Jewish anxiety about the hygiene of his Eastern European Jewish companion.”

Other revelations in the unexpurgated diaries include Kafka’s musings about his own sexuality.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/5R34UEXREBCYTMACRIVT7J4KLM.jpg)