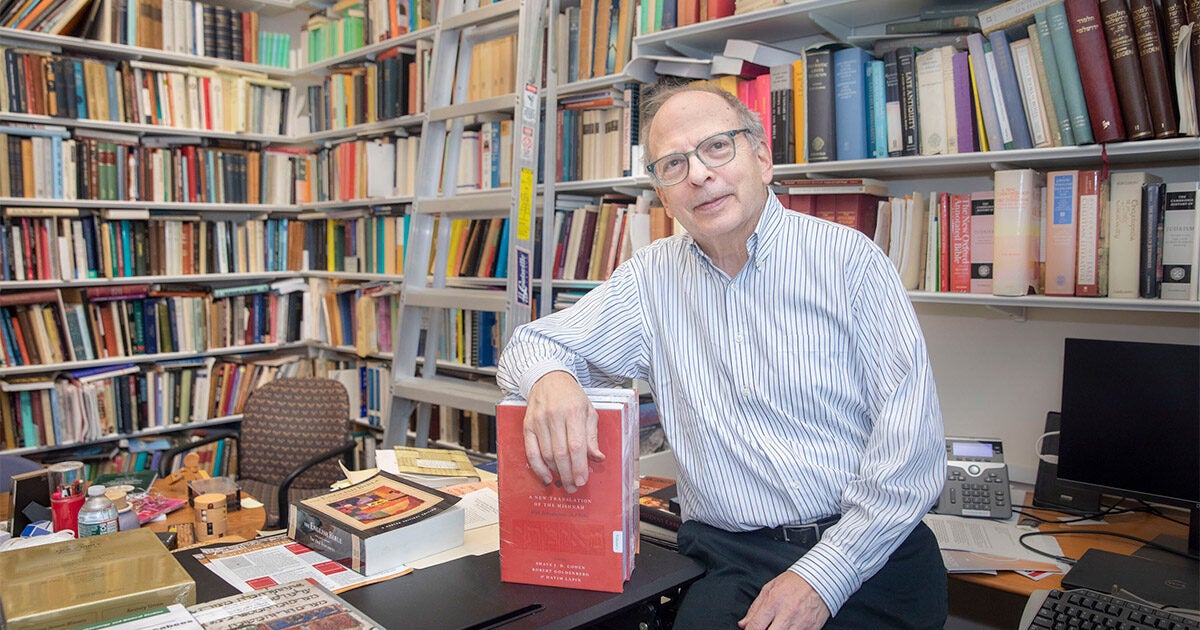

Shaye J.D. Cohen works in an office with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves on all four walls. Volumes in English, Hebrew, and Aramaic are piled on every available and makeshift surface. Most of the texts are bound in leather, with pages as translucent as onion skins. The speckled pattern of the wool sweater Cohen wears is so similar to the stacks that he appears in near-camouflage at his desk.

Cohen, the Nathan Littauer Professor of Hebrew Literature and Philosophy in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, had always imagined translating the Mishnah into a single volume. Recently, he and two co-editors completed a daunting, decadelong journey attempting to do just that. The culmination was the publication of The Oxford Annotated Mishnah, presented in three volumes by Oxford University Press.

It is traditionally believed that this ancient body of Jewish law was given to Moses on Mount Sinai alongside the 10 written commandments. The Mishnah, known as the “oral Torah,” was memorized and passed down through recitation for generations, a basis for debate and interpretation meant to be deciphered in community.

It was eventually redacted and written down around 200 C.E., although exactly when and who ultimately edited the text is up for debate. But Cohen knows, “At some point in its history, the Mishnah does get written down as a book.”

Today, this cornerstone of Rabbinic literature is learned in book form — broken down into six sections (sedarim) containing 63 tractates (massekhtaot). Cohen, who has pored over the Mishnah since his own early yeshiva education, affectionately refers to it as “unyielding” in its arguments over Jewish law. The text breaks down in detail how virtually every important aspect of life should be lived, from how an oath is taken or broken, to the offering of charity, or negotiating a marriage contract. Even though it is prescriptive, there is still significant room left for interpretation and debate in conversations that continue to take place in Jewish study halls and synagogues around the world.

Cohen says that unless one has years of Jewish day school education and a strong grasp of Hebrew under the belt, reading the Mishnah can feel as disorienting as breaking into the middle of a complex conversation between strangers.

He set out to change that, somewhat naively, on his own at first. “I thought to myself, ‘Well gee, how hard can this be?’ I started to sit down and do it and after several months working on one tractate, I realized I would probably not live long enough to finish the project.” He switched tacks.

The result is what Cohen refers to as a “a group project.” Totaling 1,256 pages across three volumes, it was published in September and co-edited by Cohen together with Robert Goldenberg and Hayim Lapin. The process took more than a decade, harnessing the translation and interpretation skills of 50 scholars of diverse backgrounds from academic and religious institutions around the world. Sadly, Goldenberg didn’t live to see the publication, and the project proved too expansive to be printed into the single volume that Cohen had envisioned.

“Ultimately, what we tried to accomplish was to make the Mishnah accessible to people for whom it was otherwise inaccessible,” Cohen said. The $645 price tag makes the work less than financially accessible to all, but he expects that a more affordable edition will be on the horizon soon.

Prior translations of note paved the way for this one. Cohen nods to a 1930s edition by Herbert Danby, an Anglican priest working in the British colonial administration in Jerusalem. “He gets a big gold star and credit for giving us the language of the Mishnah,” Cohen concedes. “He’s the first one as far as I know to translate the entire Mishnah into English.”

None of Danby’s thee’s and thou’s appear here. The Oxford Annotated Mishnah is broken into lines that appear more like poetry with sections short enough to be studied on a lunch break and kept in the back of the mind over an afternoon. Cohen said, “We have lots of white space on the page. We try to break down sentences into short phrases. We have running headers in the text to help the reader realize we have a slight change in focus.” Occasional footnotes define obscure words or manuscript variants.

Cohen said that the endeavor easily could have lasted beyond any of the contributing scholars’ lifetimes if they had been determined to reach consensus on every minute concept. Their compromise on a more realistic timeline began with how they approached the annotations.

He briefed contributors, “Our goal is to always provide enough information to the reader so that the text makes sense — and then you stop.” What he didn’t want was a prescriptive commentary that told readers how to understand the Mishnah.

“This isn’t beach reading,” Cohen said, smiling. “The goal is for the intelligent, serious reader to make sense of the text and move on.” He hopes that the translation will open up the Mishnah to scholars of early Christianity and other audiences that have had difficulty finding an entry point to the work.

To achieve that result it wasn’t necessary for each of the contributors to translate the Hebrew words identically. In fact, it is this disagreement, and the conversations that come from it, that make the experience of engaging with the Mishnah exactly what it is today.