Lagta Hai Translator Full Mood me hai. One more video of #AmitShah were wrongly translated in Kannada. #karnataka #bjp #madya pic.twitter.com/aZRaR9stUE

— Syed Aleem Ilahi (@AleemIlahi) December 30, 2022

Lagta Hai Translator Full Mood me hai. One more video of #AmitShah were wrongly translated in Kannada. #karnataka #bjp #madya pic.twitter.com/aZRaR9stUE

— Syed Aleem Ilahi (@AleemIlahi) December 30, 2022

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

How to Translate Foreign Languages With Hotkeys in Windows 10 & 11 MUO - MakeUseOf

This year I bought a strange holiday gift for my kids: I gave them dictionaries. More specifically, I gave them dictionaries that were published before the word “woman” was redefined by some dictionary publishers.

This fall, Cambridge University Press redefined woman to include not only “an adult female human being,” but also “an adult who lives and identifies as female though they may have been said to have a different sex at birth (example, ‘Mary is a woman who was assigned male at birth.’).”

Wits quickly supplied additional definitions Cambridge should consider, such as, “duck: a shark who lives and identifies as a duck though they may have been said to have a different species at birth (example, ‘Blue is a duck who was assigned shark at birth.’).”

If we were in the water and someone yelled, “Duck, duck!” we’d turn around to look because ducks are no threat. If someone yelled, “Shark, shark!” we’d get out of the water as fast as possible because sharks are very much a threat. Redefining “duck” to include “shark” would be a corruption of language because it would not allow us to communicate what we actually mean, and also would obscure the potential threat sharks pose. At best the redefinition makes us incoherent; at worst, it results in our harm or death.

“Duck, duck, the pectoral-fin-having kind of duck!”

For women, the conceptual erasure of their material reality has come swiftly, even as their actual material reality so often remains the justification for their abuse. While certain legal fictions have been long accepted in society — for example, it’s unremarkable to call the guardians of an adopted child their mother and father even though they are not biologically related — newer legal fictions are not as innocuous.

Since 2010 in Great Britain, an individual can, under certain circumstances, receive a Gender Recognition Certificate that allows them to change the sex on their government documents. This is “a legal fiction” because the person’s material bodily sex has not changed; only the sex marker on their government documents has.

We know this is a legal fiction even under British law because the older sister of a male heir of a noble peerage (the UK’s system of ranks and titles) cannot use a Gender Recognition Certificate to claim that she is now the true heir because the certificate says she is male.

The material, biological reality of her sex has not disappeared in actuality. Likewise a male heir cannot lose his noble title if he obtains a certificate that states he is female; his favored male sex can never be taken from him. The government reasoned that “by stating that where a peerage is concerned a transsexual person is considered in his or her birth gender we avoid anomalies of succession.”

But those are anomalies that would disfavor men, causing them to lose out to women. Unfortunately, the government appears less interested in anomalies that are created by this legal fiction that disfavor women, causing them to lose out to men.

The same week that Cambridge changed its definition, a U.K. judge ruled that the 2018 Gender Representation on Public Boards Act, which mandates certain percentages of women on public boards, included as women not only females but also individuals with Gender Recognition Certificates stating they are female. Thus a public board could be comprised of all biologically male-bodied persons and still fulfill its obligations under the act.

We see the same double standard at work in other recent rulings. Janice Turner of the Times points out, “The U.S. rowing federation has opened its female category to anyone who ‘identifies as a woman.’ (This, remember, is a sport with a huge male-female physical disparity.) But hey, look at new mixed rowing rules. ‘Boat entries in this category must include 50% athletes assigned as female at birth’ — i.e. no extra dudes in your team because it would be unfair to other dudes. How do you define ‘man’? Someone who never loses out.”

I would argue these legal fictions about sex are not just unfair and unsporting, but also in many cases harmful to women. First, how can you possibly organize for women’s rights when the category of women includes biological men? You are reduced to the inanity of our current discourse over “uterus-havers” and “menstruators,” when those neo-categories are wholly incapable of pointing to the human beings living in female bodies. In one fell swoop, you have made women incapable of articulating whose rights need protecting — even though everyone still knows whose rights are being lost. Didn’t we have an unambiguous word for those human beings? Well, we used to.

Worse, you prevent women from protecting themselves. Our foremothers bequeathed us a variety of ways of detecting, avoiding and mollifying threatening males. One of the major breakthroughs in women’s rights was the right to single-sex spaces, such as women’s restrooms. An extension of this right was the Geneva Convention’s upholding the right for women prisoners to be held in single-sex facilities.

Now, however, we have women accosted by men in women’s restrooms, and women who dare say anything are too often vilified for calling them biologically male. Even worse, we have had the most vulnerable women — women prisoners — trapped in cells with biological males, which has already resulted in physical abuse and allegations of rape.

When the ducks cannot say “That’s a shark,” or women can’t say male, you have stripped from them the ability to even identify those who may harm them. That we have so corrupted our language to the favor of men, by asserting that biological males can be “women” and must be called “women” if that is what men want, is deeply wrong.

I, for one, will not bend the knee to this blatant misogyny, so I’m buying those uncorrupted dictionaries while they still exist. Just as the Amish have kept alive their own dialect of English, so dissenters from this conceptual mischief must do the same, and pass uncorrupted language on to those who follow them. For women and for men who value and respect women, the stakes are just too high for complacency.

Valerie M. Hudson is a university distinguished professor at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University and a Deseret News contributor. Her views are her own.

Google’s logo. Courtesy of iStock

By Mira Fox December 27, 2022

We often talk about the fact that there are large swaths of the U.S., and of the world, where people have never encountered a Jew. And, it turns out, if they were curious to learn more about Jews, and Googled “Jew,” the top result would be a dictionary excerpt defining the term — lowercase — as an offensive verb meaning “to bargain with someone in a miserly or petty way.” You had to click a button to see more definitions before finding an entry about the ethnicity or religion.

On Twitter on Tuesday, Jews tweeted a screenshot of the definition in outrage; as of early afternoon on Tuesday, Google appears to have remedied the issue. The search now brings up a dictionary excerpt defining “Jew” — uppercase — as “a member of the people and cultural community whose traditional religion is Judaism and who trace their origins through the ancient Hebrew people of Israel to Abraham.”

Hey @Google, why does the top search result for "Jew" show up as this? This is incredibly offensive and antisemitic. pic.twitter.com/fz2WuXf93w

— Alejandra Caraballo (@Esqueer_) December 27, 2022

Google often displays what are known as “snippets,” or definitions and excerpts from other sites that sit at the top of a list of search results, without requiring the user to click through to read the original article or page from which they are excerpted. This is particularly common with definitions, which are usually sourced from Oxford Languages, a dictionary company.

There is a disclaimer that accompanies the dictionary snippets, which notes that “Google doesn’t create, write, or modify definitions. Dictionary results don’t reflect the opinions of Google.” The disclaimer section says that Google will include offensive words — always labeled as such — to ensure that the definition is comprehensive. But it says that the search engine will “only display an offensive definition by default when it’s the main meaning of the term.”

The verb usage of Jew is certainly not the objective meaning. So why was the offensive verb the top result instead of, you know, the religion and ethnicity that’s been around for thousands of years? In a roundabout way, it’s the ancient people — or stereotypes about them, to be specific — that generated the derogatory verb usage in the first place, so that certainly supersedes the offensive usage as a main meaning.

A brainstorm with colleagues brought up a few theories, but none of them quite held up. Is Google not case-sensitive, meaning it defaults to searching for jew in its lowercase usage? Google Trends, a tool that analyzes the popularity of top search queries, does not differentiate between a search for the popularity of “Jew” v. “jew,” confirming that the search engine cannot tell the difference between cases. But if that were why the offensive verb were popping up, results should always favor the lowercase usage.

Yet searching “turkey” brought up the nation, not the Thanksgiving bird. Searching for “china,” similarly, brings up the country, not the material your grandmother’s tea set is made of.

Perhaps Google puts up the most frequently used or searched-for definition? It’s impossible to confirm which usage is more common, thanks to Google Trends’ lack of case-sensitivity. But from my many years online, in a wide variety of arenas, it seems unlikely that Jew is used more frequently as a verb than as a proper noun. Even antisemitic white supremacists and conspiracy theorists tend to talk — rather nonstop, actually — about the Jews in the word’s proper noun usage.

Plus, a search for “august” brought up the adjective instead of the month, despite the fact that the month is almost certainly used more frequently. So that puts to bed the idea that the search engine defaults to prioritizing a word’s most frequently used form.

Another theory: it could be the algorithmic tailoring. Users often get different search results on Google, depending on what the search engine’s algorithm thinks you’re likely to want to see. Perhaps you recently were researching synonyms for “big” so a search for “titanic” brought up the adjective, and not the boat. (For me, it pulls up the cast of the movie; movie casts are a frequent search of mine.)

The algorithmic tailoring seems like an unlikely culprit for the Google result for “Jew,” however, given that Jews were the ones raising the alarm about the offensive result — and the fact that many different people all got the same result.

Google’s algorithm is complex, and uses large sets of data to determine how to rank results and what to show users, including concepts such as “relevance” and “freshness,” according to a page explaining its ranking processes. Perhaps a page or definition using “jew” as an offensive verb was going viral, and that elevated Google’s algorithmic “freshness” assessment — though Google’s public information on ranking specifically says that freshness is more important to news-based queries than when determining which dictionary definitions to show.

As of publication, the search engine had not replied to a request for comment. The offensive verb definition is currently not listed in the dictionary results at all, even when you scroll down. Honestly, though, that seems wrong too.

We trust that the people who teach us new things know best and we are just trying to soak in their knowledge. But in reality nobody can know everything and challenging them should be taken by them as an opportunity to learn themselves instead of being offended that a student dared to question their teaching, as it often happens, especially in schools.

It also happened to a 16-year-old Sunday school student who noticed that the teacher was incorrectly translating the Bible and pointed it out. This was not taken well and the teen was kicked out, which made her parents very upset.

More info: Reddit

Image credits: Greg Chimitris (not the actual photo)

The Original Poster (OP) lives with her mom and stepdad Brad and his children who all go to Sunday school. The teen describes the family as very religious and has a lot of rules, such as girls having to wear skirts all the time and going to church several times a week.

In the comments, the author of the post said that she is from the Southern US and she is not sure what kind of denomination her stepfamily belongs to, but she believes that it’s the Holiness movement.

As Britannica explains, the Holiness movement is a Christian religious movement that has its roots in the 19th century United States and is “characterized by a doctrine of sanctification centring on a post-conversion experience.”

Most people who belong to this church believe in “Christ’s resurrection, truth in the scriptures, justification, sanctification, baptism of the Holy Ghost, divine healing, and the premillennial return of Christ to earth.”

Image credits: throwaway_394757

In the OP’s eyes, her stepfamily’s relationship with Jesus is toxic, and the things being talked about at church are “superstitious misogynistic nonsense.” What is worse, she is being forced into it and refusing to go to church turned into a big argument.

Her own mother asked her to just go in order to keep peace and because it’s a thing they do as a family, although it’s mostly enforced by Brad, who has almost made it a mission to convert his stepdaughter and save her soul.

Not only did she have to go to church with the family, but also attend a Sunday school. Sunday school, also known as church school or Christian education, is “school for religious education, usually for children and young people and usually a part of a church or parish.” It was introduced in Protestantism and most of the learning there is related to teaching the principles of the religion and reading the Bible.

Image credits: throwaway_394757

It’s always interesting to know what others believe in and what their religious scriptures say about the world, what values they instill and what stories they choose to illustrate their points with, regardless of whether you’re religious or not. But being forced to believe in it, agree with it and be interested in it is a different thing.

On top of that, the OP has a feeling that their teacher thinks that her age group is a bunch of stupid girls who don’t understand anything, but wanted to show off as smart by translating the Greek version of the Bible himself. That was pretty annoying because he wasn’t doing a very good job.

Turns out, the OP actually knows the version of ancient Greek to which the Bible was translated. In the comments, the teen explained that she goes to a private school that is known for preparing students for the Ivy league colleges and it has more language choices than your average school. Among Mandarin Chinese, Arabic, Russian, French, and Spanish, they teach ancient Greek and Latin, which the OP chose as she is interested in history and science where these two languages are often used.

Image credits: throwaway_394757

Image credits: George Redgrave (not the actual photo)

At this point, the OP had nothing to lose, so she brought a dictionary to be able to correct her teacher and started interrupting him by pointing out his mistakes. Although the teen was right, the teacher was quite annoyed and complained to the pastor, who decided to kick her out of Sunday school…

Both Brad and the OP’s mom are mad that the teen couldn’t sit through school quietly and want her to apologize for derailing the class, which made the teen wonder if she unnecessarily acted out as it was the first time she had been to a Sunday school and it’s the first church she has ever been to.

Image credits: throwaway_394757

Readers of the story thought that the OP’s rebellion was very sophisticated, because the teacher was actually lying and shut her down immediately without trying to create a discussion.

But the bigger conversation was about how wrong it is for the parents and the teacher to push on a religion on a person who is not interested and went as far as calling it child abuse.

Image credits: throwaway_394757

The teen not only stood up against her parents by knowingly annoying the teacher, publicly saying that she doesn’t want to be there, but she also wasn’t going to listen to misinformation being spread.

This is exactly how Moses ended up being represented as a man with horns. Various illustrations, paintings and sculptures depict Moses with horns because that’s what the translation from Hebrew into Latin Vulgate said. The translator, St. Jerome, wasn’t weirded out by the image, as back then, horns didn’t have the association with the devil.

But now we know that St. Jerome made one of the most famous translation errors in history, which influenced how we imagine Moses and how our art depictions looked for centuries. As Dr. Ingrida Gudauskienė, who has a degree in theology explains, there are two very similar words in Hebrew, “qāran” and “qeren,” which mean “to glow” and “horns” respectively. The mistake probably wasn’t malicious as it was due to the Hebrew text being written only with consonants, so both words would have been written “qrn.”

Image credits: Steve Snodgrass (not the actual photo)

The OP tried to prevent her teacher from making translation mistakes because as the famous example shows, it creates ripples. But he took offense and the student was kicked out of lessons altogether, which on one hand was what the teen wanted, but on the other hand, her parents are pressuring her to apologize.

We would like to hear your opinions and reactions to the story. Do you think it was worth challenging the teacher knowing what consequences await? Do you agree that forcing someone into a religion is abuse? Let us know your thoughts in the comments.

Editor’s note: The Catholic Book Club is reading Michael Moore’s new translation of Alessandro Manzoni’s classic Italian novel, The Betrothed.

Modern Library

704p $28.99

Moore’s published translations range from 20th-century classics to contemporary novels. He is the former chair of the PEN/Heim Translation Fund and has a doctorate in Italian from New York University. For many years, he was also an interpreter at the United Nations and a full-time staff member of the Permanent Mission of Italy to the United Nations.

The following interview with Mr. Moore has been edited for length, clarity and style.

"Manzoni forged the modern Italian language, and his novel—yes, he wrote only one—is still the greatest novel in the Italian language."

James T. Keane: This book was a commitment to read; I can only imagine what it was like to read in a different language, then translate. Why this book and why now?

Michael F. Moore: I promessi sposi (the original Italian title of The Betrothed) is a beautiful, sweeping novel that every Italian has read. While I’ve translated many contemporary authors (including Pope Benedict XVI), I have always wanted English readers to have a deeper sense of Italian literature and culture. Tradition weighs heavily on Italian artists, and when they create, they have to contend with that glorious tradition. Manzoni forged the modern Italian language, and his novel—yes, he wrote only one—is still the greatest novel in the Italian language.

I felt that it was underappreciated in the United States because the existing translations were inadequate; failing to capture the energy, eloquence and range of Manzoni’s prose.

But while I started translating with the ambition to restore this novel to its rightful place in world literature, as I got closer to publication, circumstances in the world lent the novel a renewed importance. First and foremost, the Covid-19 pandemic. In two chapters of the novel, 31 and 32, Manzoni describes the outbreak of the bubonic plague in Milan in 1630, in a report that mirrors, eerily, the moment we have just been through.

The portrait he gives of the Capuchin brothers, to whom the municipal government assigned the responsibility for tending to the sick, the dying, and the dead from the bubonic plague, highlights both their Christian vocation and their practical know-how. Cardinal Federico Borromeo, the archbishop of Milan during those years, reminds the priesthood of their duty to serve the poor and needy. And the hero of the story is Padre Cristoforo, who is unafraid to confront the powerful and sacrifices his life in the service of the plague victims.

The novel has a powerful ethical dimension, sensitive to the moral complexities the characters face but nevertheless clear and firm in its exhortation to justice, faith and forgiveness.

"I have always wanted English readers to have a deeper sense of Italian literature and culture."

Over the years, The Betrothed has appeared in a number of different lengths, versions and even translations. Did you read all the previous versions, or did you have an ur-text you chose?

Manzoni wrote three versions of the novel. The first, Fermo e Lucia, in 1821, was only published in recent years, primarily for scholars. The second, I promessi sposi, in 1827, and the third, with the same title, in 1840. In that last version, he revised the language but otherwise left the novel unchanged.

I consulted an edition that compares the 1827 and 1840 editions, to understand the care he took in the writing process, but I translated the 1840 edition. On the title page you will notice that it says, “Edition Revised by the Author,” which is what that 1840 edition says, to indicate Manzoni’s rewriting of his own novel.

After I finished my first draft, I consulted two previous translations, as a way of double-checking the accuracy of my version. Where the translations were very far apart, I went back to the Italian I might find a better way to interpret a passage, a word, or an idea.

How would you categorize The Betrothed in terms of genre? Is it a romance, a historical novel, an epic, a war novel? Or a palimpsest of all of these?

He called it a historical novel, in the tradition of Sir Walter Scott, who was hugely popular throughout Europe at the time. I would call it an epic of the Italian people. It is historically faithful, but with elements derived from sources as varied as opera comica and the gothic novel (like Frankenstein or The Mysteries of Udolpho).

"Throughout the translation, I was doing a balancing act between loyalty to Manzoni’s style and a wish to write in good modern American English."

A number of years ago I took a class on Don Quixote taught by Edith Grossman, who had just published her translation of Cervantes’s classic. She mentioned that in doing her translation, she consciously tried to use language with Latinate and Romance-language roots, if she had the choice between those and more Germanic-sounding words, so that the book would be in clear English but also convey the Spanish roots. Did you have a similar strategy with your translation from the Italian originals?

Edith is one of the people who encouraged me to take on the novel, advising me to just try a few pages, to see if it was a good fit.

Throughout the translation, I was doing a balancing act between loyalty to Manzoni’s style and a wish to write in good modern American English. I wanted the language to sound neither too antiquated nor too contemporary. His sentences can be very long, and his paragraphs interminable. I sometimes broke them into smaller pieces, without sacrificing any content or word play.

While I did sometimes indulge in Latinate words, I was more interested in restoring the popular appeal of the novel. Too often the classics are rendered in a decorous, elevated style; an approach that would have violated Manzoni’s purpose. He wanted to bring written and spoken Italian closer together. You can see his critique of elaborate language in different parts of the book, particularly at the very beginning, in his introduction, and in his quotations from 17th-century texts.

"Too often the classics are rendered in a decorous, elevated style; an approach that would have violated Manzoni’s purpose."

What were the biggest struggles in translating the text into contemporary English?

Every now and then I would be tempted to use a contemporary expression, like “give me a break” or “get lost,” to capture the emotional temperature of an expression, especially in dialogues. To avoid being too contemporary, I always checked the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, which tells you the earliest date a word or expression was used. I was aiming for expressions that are still in use today, but that have their roots in the 19th century—or even the 20th. But I always wanted the language to sound natural, not stilted.

In general, the main challenge was to capture Manzoni’s shifts of register: One moment he is serious, the next minute he’s ironic; he’s poetic, but he writes with the accuracy of a historian; he’s light-hearted but he’s dead serious. The novel really is an encyclopedia of styles.

I am a big fan of Liu Cixin’s science fiction novels, which are translated from Chinese but also require fairly significant footnotes to explain to an American audience what the author means when he references historical events Americans are ignorant about (for example, the Cultural Revolution, or famous Chinese medieval figures). How did you handle this quandary between providing necessary context and bogging down the flow of the text, given that history is a major player in The Betrothed?

I didn’t want a lot of footnotes, which I felt would distract from the story. Since Manzoni himself was explaining events that had taken place 200 years before (he wrote in the 1820s; the story takes place in 1628-1630), he often explains events carefully. To help the modern reader, we have a map of northern Italy at the time of the story in the first pages, and at the end of the novel a note on the historical background and a list of historic characters.

Having said that, one of the harder things to convey was courtship, especially for today’s young people. The most that Manzoni says about Renzo and Lucia’s courtship before their wedding day is that Renzo “discorreva” with Lucia: literally, he spoke with her. In traditional society, for a man to even approach a single woman was to express intentions other than friendship!

"Manzoni’s voice can cut through the fog of our grief with wisdom, wit and an overarching appeal for charity."

Why do you think this novel (and this translation) have struck a chord with contemporary readers?

This is a novel about a world beset by corruption, social injustice, famine, plague, all aggravated by war and foreign occupation. Sound familiar?

Manzoni lived through a tumultuous time, from the French Revolution right on through to the birth of the Italian nation. He recognized the need for change but also feared the tyranny of the mob. At the center of his novel—which takes place against the background of a great conflict between Spain, France, and the Holy Roman Empire—is a humble peasant couple that simply wants to get married and is prevented from doing so by the whims of the powerful.

These themes all resonate with our own age. We have been through a devastating period, with a pandemic, politics at war with science, rising authoritarianism in the world and a popular outcry for justice. The failures, even the evils of capitalism have become glaring (I can’t stop thinking of the plight of the elderly in nursing homes, left to die without the comfort of family or loved ones by their side), and we’re struggling to find a way forward. Manzoni’s voice can cut through the fog of our grief with wisdom, wit and an overarching appeal for charity.

I think my translation has struck a chord because it speaks with all of Manzoni’s eloquence and musicality but in the language of today.

Pope Francis has described this as one of his favorite novels of all time. Any speculation why?

In public appearances, he has mentioned two aspects. First, that it is a story of a young couple overcoming obstacles before they can finally marry. He sees the novel as a kind of parable of the paths people in love will have to travel before they can be together. Second, that he sees Cardinal Borromeo as a good example of the pastoral vocation. Let us remember that a “pastor” is literally a shepherd, the good shepherd who looks after his sheep.

On a more personal note, Pope Francis has written me a letter of appreciation citing what he thinks the novel’s virtues are: “Your efforts will help to spread the word of Manzoni’s masterpiece, which maintains its great relevance and solid educational and spiritual value. Today the world needs to regain the culture of providence, hope, and forgiveness.”

***

Not a member of the Catholic Book Club yet? You can read up on our past book selections here, and you can join our Facebook discussion group here.

As the cold winter began to grip Canada this year, my partner and I decided to escape the snowy weather and flee to her homeland in Mexico for a few weeks. I have been learning Spanish through Memrise for the past few months, which has taught me the basics of greeting others and ordering another beer, but I am far from fluent. Thankfully, my fluency in French is helping me pick things up quicker due to the languages’ similarities, but I usually rely on my partner, who is a native speaker, to help translate the rest. For this trip, though, I wanted to give her a break and be more self-reliant. So I downloaded the Google Translate app as my main companion and aid in navigating the local language for this journey.

See also: 10 best Spanish to English dictionaries and phrasebooks for Android

Translate’s proposed features seemed promising. “Oh, it will be easy to translate entire conversations, and I bet people will be receptive to it,” I thought. Boy, was I wrong. After using Google Translate while traveling, I can attest to some crucial limitations. May this serve as a warning to any tourists thinking they can get by solely using the app without at least some knowledge of the local language.

256 votes

Adam Birney / Android Authority

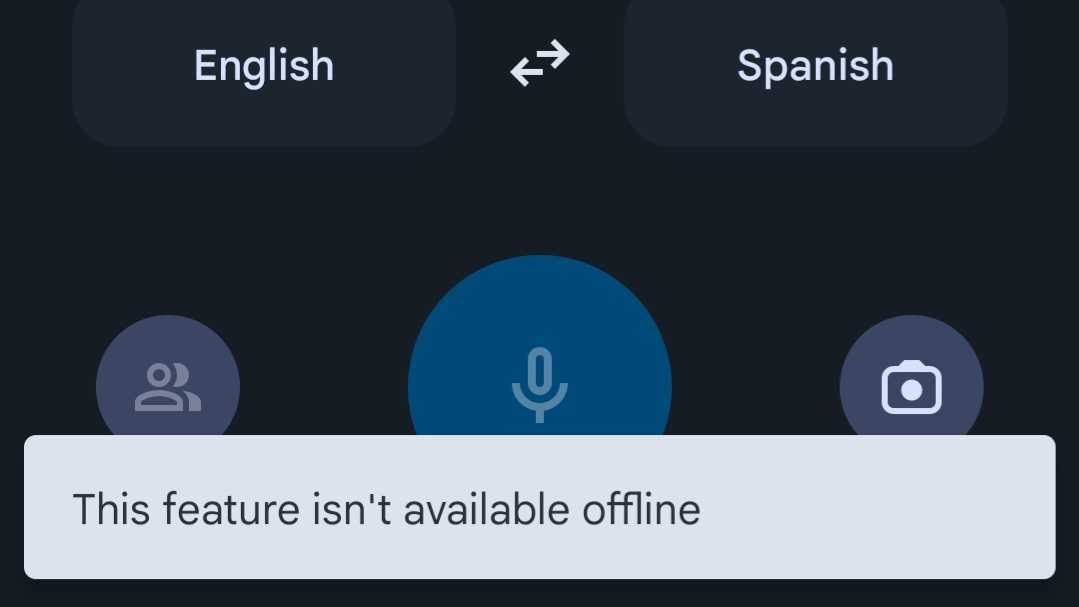

Let’s start with the biggest Google Translate limitation while traveling. The app’s description states that “you can download languages onto your device,” which supposedly “lets you translate them without an internet connection.” Great, so if I download Spanish before flying off, I should be able to use all of the translation features offline, right? Wrong. Of all the features that Google translate offers, only one worked for me offline: basic text translation. The conversation, camera, and audio modes all required an active connection.

Of all the features that Google translate offers, only basic text translation worked for me offline.

Google Translate is supposed to support offline camera lens translations, but I never once got it to work during my trip. Despite downloading both English and Spanish beforehand and granting all the relevant permissions, I always encountered an error message when disconnected from the internet. To be clear, offline camera translation seems to work for most users — my Android Authority colleagues confirmed that on their devices — but judging by many reviews on the Google Play store, I’m not the only one who keeps getting the error message.

The introduction of Google Lens to replace Google Translate’s previous photo mode might be responsible for this bug, as that update only rolled out a month ago. Many users have also noted that you can no longer select text to translate word by word; Lens will just automatically translate an entire page. In its current buggy state, it was a letdown that this offline selling point never worked for me. Instead, turning my data on and off in each instance (at exorbitant roaming rates) became a nuisance, given that Wi-Fi was scarce.

Turning my data on and off in each instance became a nuisance, given that Wi-Fi was scarce.

With only typed text translation working offline, the whole prospect of downloading a language became rather redundant. The basic text translation is handy in a pinch if you forget one or two words. But I had already saved most of the short phrases I knew I’d use, such as greetings or asking where the bathroom is, to my favorites beforehand. I did so because I anticipated referencing them offline.

More importantly, the other features are the ones I would imagine rural travelers relying on more. For example, I depended on Google Lens to translate signage, know what to order on a menu at a restaurant, or read plaques within local museums. Conversation mode would’ve been great when communicating with locals too; instead, typing text and handing the phone back and forth was nowhere near as efficient or intuitive as the microphone.

When you are online, the conversation feature works pretty well for one-on-one interactions. It has a friendly greeting message you can show to whomever you wish to speak with. The microphone didn’t always catch every word in my interactions, and I found the slower each of us spoke, the more accurate it was. But as soon as I threw a third person into that mix, everything fell apart.

In larger group settings, using this conversation mode really slowed down social interactions’ pace. If you’ve ever been in the trenches of a Mexican family gathering, you’ll know how fast they can rapidly poke fun at one another. But because the conversation mode is only designed for two people, it doesn’t give you an opening to engage with a party. Combined with the microphone’s delicacy, multiple people speaking simultaneously all but ensure translations get jumbled.

Because the conversation mode only works between two people, it doesn't let you engage with a larger group.

When Google Translate comes short during a conversation, it can feel like an imposition to ask others to repeat themselves or slow down while they are having fun. As such, I always found myself a few minutes behind the conversation, always catching up. I did try just using the central microphone instead of the conversation mode, thinking I could just parse the transcript to the relevant speaker myself. But that came out even more disorganized. Plus, if you’re not using the feature with someone else, it can look like you’re just on your phone and not paying attention.

Ultimately, my partner was much more reliable in keeping me up to speed. Unlike Google Translate, she didn’t have to translate every single word literally and could just give me the gist of what was being said so I could follow along.

The universal translator (UT) is a fictional device from Star Trek, used to used to decipher and interpret alien languages into the native language of the user.

You would expect translating between languages to be easy once you have downloaded the right dictionaries. Just scan or type the word, find the matching one in the other language, and then output a translation one by one. Unfortunately, it isn’t quite so simple. Some things work great when you’re connected, but if you venture outside of civilization, nearly all the language features are left by the wayside.

Google released a big update to the Translate app in November that changed a lot of the UI and replaced the camera translation with Google Lens. Users had hoped this would bring improvements, but personally, all I got were bugs. Hopefully, these are just growing pains that Google can learn from and fix.

Google likes to boast about having over 100 languages at your fingertips, but we are far from Star Trek levels of real-time translation.

In the app’s current state, my experience while traveling abroad was pretty underwhelming. Google likes to boast about having access to over 100 languages at your fingertips. Still, that promise fell short when I realized all the more helpful things depended on Wi-Fi or data, which can be scarce and expensive in a foreign country.

Even when connected, translating things like airport announcements with the microphone was impossible. Granted, that could be more due to the quality of the speakers, but my ears, and brain, were ultimately more reliable than my phone. We are far from Star Trek levels of real-time translation.

Learning the basics of a language can go a long way. Don't rely on Google to speak the language for you.

Instead, I learned it pays to know the basics of the language for yourself. Learning social introductions, numbers, and the names of destinations doesn’t take much effort and can go a long way. Don’t rely on Google to speak the language for you. If you are lucky enough to have a travel companion that can fill in the missing gaps, that’s a far better service than Google Translate could ever hope to be.

Even with advances in AI learning, humans are still better at understanding context and communicating the main point efficiently. In comparison, Google tries to translate each word individually and produces errors if it doesn’t catch everything. But who knows? Maybe one day, we will have automated real-time multi-lingual translations between multiple people like Google promised during I/O earlier this year (see the video below). By the looks of it, however, that day is still far off.