It is a far more challenging task than it may first appear, said junior Dan Krill, who took the class last spring. The use of unfamiliar idioms and colloquialisms from 19th-century French, references to unknown people or places and handwriting that is difficult to decipher all add to the complexity.

“On the first day of class, we did a practice translation, and that’s when I realized, oh, it’s not going to be that simple,” said Krill, a computer science major and French minor. “There are so many things to consider, so many historical and linguistic questions, but it’s also really cool. It’s almost like solving a puzzle when you’re piecing this whole message together.”

One letter in particular stood out to both Krill and his partner from the class, junior Monica Leon, who is majoring in political science and French. The letter, which was written to Father Sorin from a Brother Julien who sought to come to the U.S. to work at the University after having taken his vows, seemed indecipherable to them on their first reading.

It was only when Father Haake challenged the pair to read the letter aloud that they began to understand that Brother Julien, who had not had much formal education, was writing phonetically. The moment allowed them to think about the French language in a new way.

“There were a lot of spelling and grammatical errors that made the language really difficult to understand at first,” Leon said. “But Father Greg encouraged us to read the letter out loud and sound out the words, and that’s when it started to make sense. And it ended up being such an interesting exercise. I’m so grateful for Father Greg’s guidance and help throughout the entire process.”

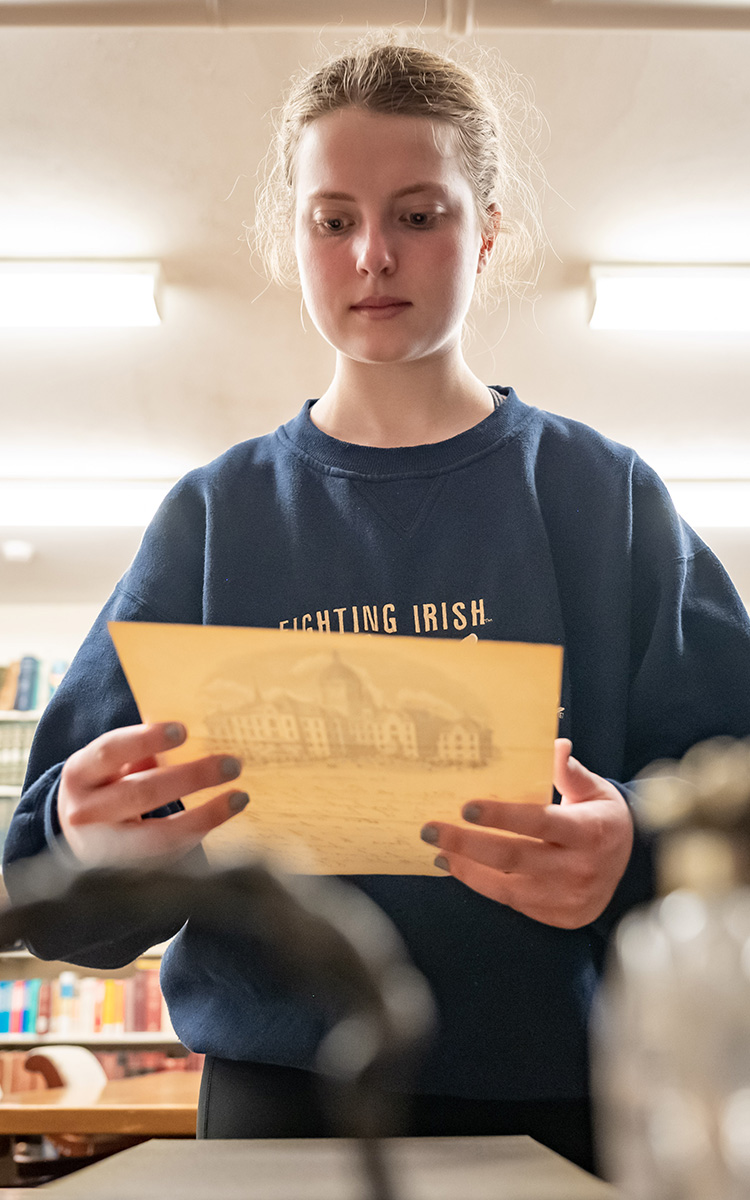

While the students typically work with high-quality PDF copies of the letters, Father Haake also sets aside a day each semester for the class to visit the University archives to view the original letters, along with other artifacts from Father Sorin, including a Bible, a passport, a pair of his glasses and a pen set.

Even though the class was only one credit, it was a deciding factor for Leon in choosing to pursue a French major — and an experience that has given her a deeper appreciation of the University’s mission and founder.

“You know, there’s the side of Notre Dame that everyone knows. It’s a prestigious school, a great football team, but it’s so much deeper than that,” Leon said. “Notre Dame really cares about the community and the world. There are so many students here who are passionate about going out into the world to do service. And that’s exactly what Father Sorin wanted for Notre Dame, and I like to think that he would be proud.”

Father Haake, who is spending this year as a faculty fellow of the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study, plans to focus on Father Sorin’s personal correspondence with his family when he teaches the class again next year, including letters to and from his nephew Rev. August Lemonnier, who became the University’s fourth president.

With funding from the Vernon Brink Family, Father Haake is also working to launch a website that will feature a digital exhibit of the letters alongside their transcriptions and translations. He hopes the translated letters will not only be a valuable resource for scholarly research, he said, but provide inspiration to the Notre Dame community.

“I look to Father Sorin when I'm having difficult days in my job as a priest and a professor, and I think of his perseverance, his zeal and just his abounding energy for this place and for educating young people,” Father Haake said.

“He wanted Notre Dame to make a difference in the world. He wanted to make people’s lives better, and he was relentless in doing it. It’s that spirit and that energy that inspires me, and I hope he inspires others, too.”

“Voilà pourtant notre maison commencée, Dieu sait quand elle sera finie.”

“Yet our house is begun, God only knows when it will be finished.”

— Rev. Edward Frederick Sorin de la Gaulterie, C.S.C., Sept. 3, 1843