The pin on your lapel.

A slight shoulder shrug.

The way you clasp your hands.

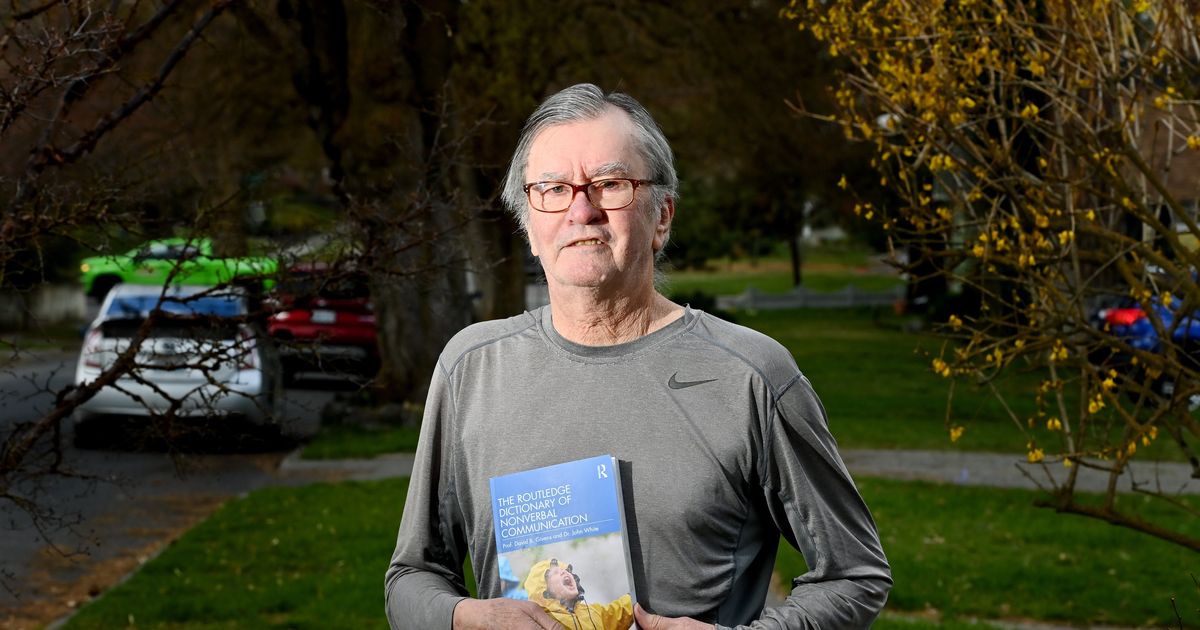

Human beings communicate in myriad ways without ever saying a word, and that has fascinated David Givens for 60 years.

He majored in anthropology at San Diego State and then received his doctorate from the University of Washington.

“Nonverbal communication is everything apart from the spoken word or manually signed words,” Givens said. “It gives us information and evolved as a way for humans to say ‘See me, I am here.’ ”

While at UW, Givens videotaped conversations between students.

“I broke them (the conversations) down into all the nonverbal signs and came up with 200 nonverbal signs for my dissertation.”

That early work eventually became the basis for the online Nonverbal Dictionary, which Givens created when he launched the Center for Nonverbal Studies in 1997.

The center’s mission is to advance the study of human communication in all its forms apart from language.

“I wanted to address some profound questions,” he said. “I wanted to do something to help people understand what it means to be human. The online dictionary is a free resource that’s used around the world.”

During the pandemic, he partnered with a colleague in Ireland to publish a print version of his online dictionary, “The Routledge Dictionary of Nonverbal Communication” (Routledge, 2021).

The book is presented as a series of chapters with alphabetical entries, ranging from attractiveness to zeitgeist, and aims to provide the reader with a clear understanding of some of the relevant discourse on particular topics while also making it practical and easy to read.

Prior to launching the Center for Nonverbal Studies, Givens taught at UW and also served as Anthropologist in Residence at the American Anthropological Association in Washington, D.C., for 12 years.

After moving to Spokane in 1997, he taught at Gonzaga University, taking hiatus for research before returning to teach online. He retired from GU in January.

Givens said what set his research apart from other anthropologists is that he studied the roles of neurology, psychology and psychiatry in nonverbal communication.

For instance, the shoulder shrug.

“It can be voluntary or involuntary and can convey uncertainty,” he explained.

The neuromuscular action gives observers a look into the brain.

“Words themselves, like court transcripts, are devoid of emotion, but add body movement, eye contact,” he said. “Lips, hands, shoulders and eyes give us a look inside at emotional cues.”

Gestures aren’t the only types of nonverbal communication,

“Take our flag,” he said. “It’s colorful and symbolic and communicates nonverbal information.”

Givens has worked with the legal system, the FBI and businesses to help decode the mysteries of nonverbal communication in various settings.

“The battleground I studied most was the board table,” he said. “With legs and torso underneath the table, it becomes a stage for hands. Hand movements reveal a lot.”

He used palm up as an example, explaining uplifted palms suggest a vulnerable or nonaggressive pose that appeals to listeners as allies rather than as rivals or foes.

When his co-author, John White, reached out to him from Dublin City University and broached the idea of compiling the online dictionary into a book, Givens was excited.

“I’m working on a second book with John,” he said. “We communicate almost every day. He’s in his 50s, so I’m slowly handing everything over to him. I’m 77, and I don’t want all this to die.”

His goal in compiling decades of research into the intricacies of nonverbal communication into book form is that readers will use it to enrich their lives.

“Understanding nonverbal communication adds color and depth,” Givens said. “You’ll see things that you’ve never seen before, and that makes life more fun.”

For more information, go to routledge.com.

Cindy Hval can be reached at dchval@juno.com.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/4RVDJDREZFHKZNEKC762SXPXNM.jpg)