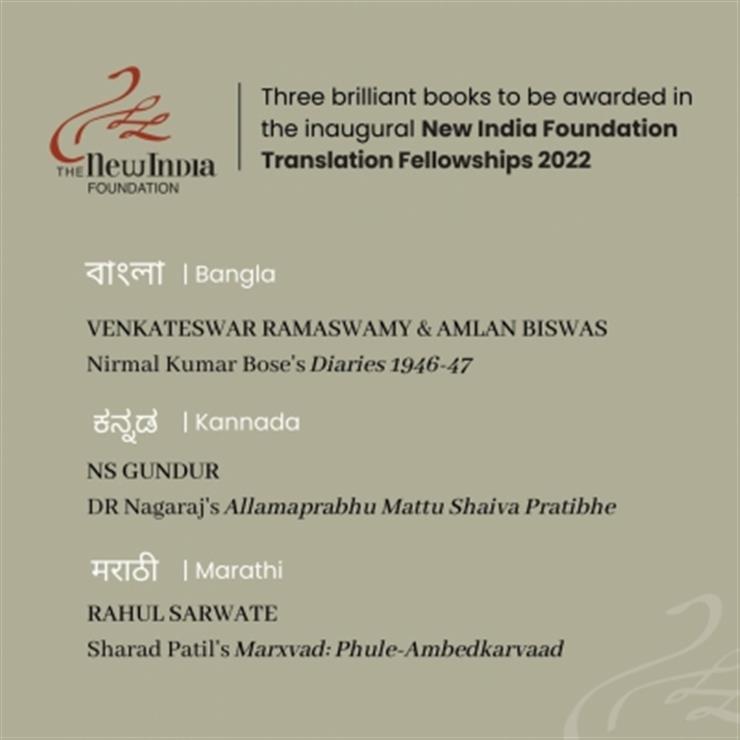

Talking Translation: Tempo

Susie Wildsmith talks to poet, translator and editor Luca Paci, the Co-Director of the Italian Cultural Centre Wales, about the joys and difficulties of trying to represent the texture and variety of contemporary 21st century Italian poetry in one parallel text anthology.

It is an unusually sunny day in an unusual year when Luca Paci and I meet for iced coffee in the refectory before his next class at Cardiff University. The world is opening up again, but, we now know, only briefly and we are giddy with joy at being able to meet and discuss poetry and more in person rather than across screens and phone lines. It has been a period of collective grief and of personal grief, a time where crossing barriers with the shared experience of poetry feels more important than ever. After a devastating summer, Paci needs ‘to hug, to be more Italian’. We need to tame lines gone unruly in the production process, to discuss the last of the changes to the text. More than that, we need to reach out, and so we do. We begin at the beginning. With the impetus to start something, mark something, make something, in a time of too many endings…

What prompted you to put together this anthology of Italian poetry?

Everybody knows novelists like Italo Calvino, Umberto Eco and Elena Ferrante but if you ask people about Italian poetry I suspect you would struggle to find a name apart from Dante. There is very little contemporary Italian poetry published in the UK apart from the usual suspects: Montale, Ungaretti and Quasimodo who are really (male) mid 20th century authors. When it comes to the 21st century there is an awkward void. I am also passionate about poetry in translation. A language without works in translation is a diminished one and will soon wither.

There’s real range evident in the selection of poets, their style and themes…

I have always wanted to give the English-speaking reader a sense of the unique and diverse texture of Italian poetry. I selected this mix of established and new poets based on my experience of the scene as a working poet and literary critic. The anthology tells the story of contemporary Italy. The politics, culture, society, current affairs and history. The (melo)drama and tragedy. I would like to think that the reader will be more knowledgeable about the present state of Italy after going through the collection. In this respect perhaps the book could work as a sociological reflection.

How did you select the translators to work with?

Translators and poets frequently travel in pairs like Jehovah witnesses. When you choose a poet there is often another poet who translates or interprets their work. It is a real labour of love and there is a lot of care and attending to the words, form and style. Many of the poems selected had been previously translated but they often had appeared in academic journals or small selections. There is something magical about the juxtaposition of two good poems in the same context; their energy is expanded, and you discover new connections.

Although you haven’t personally translated the poems in this anthology, you do work as a translator. What does translation mean to you?

Translation is a big part of my life. I translate all the time, in different contexts: at home with my (bilingual) family; at work; when I teach. Perhaps we don’t realise it but every kind of communication requires a specific degree of translating skills. You don’t need to be a professional to translate. If you explain something complicated in other words you translate.

As Umberto Eco puts it, translation is (a form of) negotiation. I’ll give you an example taken from my experience. My first ‘foreign language’ was French. I used to speak French with my wife when I was in Paris for my Erasmus exchange and then when we moved to Scotland in the late 90s I switched to English. Initially I used a kind of baby talk, so frustrating. I was working as a kitchen porter in a Tex Mex in Glasgow. It was fascinating but I could not speak, I had to listen all the time! Learning a language is a great exercise in humility. It is that kind of gentleness and humility that is so important when you translate thoughtfully. Negotiation is an essential skill here.

How has living in Wales influenced your approach to language and translation?

There are a lot of exciting things about Wales and one of them is the Welsh language. It is the only original British language that is still widely spoken. In many ways it is more similar to the Italian than English, since it has a great Latin influence. The cadence and rhythm in Welsh poetry are also very continental. So, when I translate from Welsh I often pass through Latin or French. I was very privileged to have Menna as a poet to translate. She is extremely patient and encouraging. For Bondo, her last collection of poets we had a verbatim translation which then was ‘sublimated’ into Italian in kind of alchemic process. I found that the most important part was to serve the text as well as I could. Predictably, learning another language has opened other doors of perception!

I have also had the honour of being part of the executive committee for Wales PEN Cymru for three years now. We have campaigned for freedom of speech especially in Turkey. PEN promotes literature and defends freedom of expression. We campaign on behalf of writers around the world who are persecuted, imprisoned, harassed and attacked for what they have written. There are committees representing writers in prison, translation and linguistic rights, women writers and a peace committee. We have put on an impressive number of events but still need support from the writing community. Subscribe today, the membership is only £4 a month!

What is the translation style that appeals to you most? Has this changed over time?

It really depends on the situation. As I said, translation is everywhere, we just don’t think about it. For example, if I want to crack a joke in my poor Welsh I don’t need to care about the literal translation. What is important in this context is to convey the fun, the laughter. If I succeed in it, I have performed a good translation. Grammar, structures, and the literal meaning of the joke are irrelevant in this case.

However, if I translate a poet, say Menna Elfyn, I need to know how to serve her poem in another language. I need to know a number of things about Elfyn’s use of Welsh and her style to prepare my work. And then I need to make a number of choices which are again dictated by the context. If I am translating into Italian there will be a number of things I need to explain to the reader either implicitly or explicitly.

Why was it important to you to have an editorial role rather than a translating role in the creation of this book?

One of the most difficult tasks for an editor is to give poems the right platform to be appreciated, but it is a great job and that’s why I chose it. If you succeed, you create a narrative, a story with the poems you select. Similarly writing the biographies of the poets is exciting when you read them through the lens of their works. Poems, lives and events collide on the pages and the books becomes epic. Literally: a work of epics you offer to the reader.

You are also a poet. How has that shaped your selection of poems?

I see poetry as my way of being myself in the world and as a way of making sense of the world around me. The ancient Greeks had the word Logos which is also present in the opening of the Gospel According to John: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ Words are everything and poetry knows it.

I am especially proud of the mix of genders, age, and social background within Tempo. We have Giovanna Cristina Vivinetto, a very exciting poet in terms of biography, style and content, egregiously translated by Cristina Viti. She reminds me a bit of the late Jan Morris.

Shirin Ramzanali Fazel is a great writer who deserves to be known much more both in Italy and abroad. I like the work Antonella Anedda who is translated by the poet Jamie McKendrick but also Laura Pugno and Chandra Candiani. I also gave space to poetic strands that are often suspicious of each other. Spoken word and lyrical poetry for instance. Or more experimental, concrete and rhymed.

All the poems I have included represent for me a huge dip into the poetic matter. There are different generations talking to each other and grappling with life in their own poetic terms. What fascinates me is that mundane events are transfigured, history is mythologised.

Do you think contemporary Italian poetry differs from say Anglo-American poetry?

It is very difficult to generalise because there is the risk of overlooking at the details and a lot of details make the whole picture. My impression is that Italian contemporary poetry has a number of forms but is embedded into (bio)politics. The individual is seen as a part of a nation and society that is failing his citizens, their desires and expectations. In opposition, it seems to me that the Anglo-American tradition is perhaps more focused on the individual as agent of freedom and desire. The biopolitical situation is radically different and consequently its expression is not the same. However, we can learn a lot from different traditions.

Why was it important to you that this book should be a parallel text edition?

Britain is crossing a very reactionary phase after Brexit which is a direct result of the politics of austerity enforced by the current government. This has led to the closure of dozens of modern languages departments all over the country. Over the past five years Wales has lost Italian departments in Aberystwyth, Bangor and Swansea. I suspect that German will be next. Learning a foreign language is not compulsory for GSCEs or A-levels. So, the parallel text edition becomes a strong cultural and political gesture.

We need more foreignness in our lives. We need to see, speak, be exposed to different cultures and this passes through language, translation, literature and poetry. Accessibility is so important. If the general public find Italian poetry exciting perhaps they will buy more poetry in general and develop a greater sensitivity for the humanities and humanity.

Tempo: Excursions in 21st Century Italian Poetry is a parallel text anthology in English and Italian edited by Luca Paci and can be purchased here.

Luca Paci was born in Novara, north Italy in 1970. He studied Philosophy at Pavia University and on the Erasmus programme in Paris, where he gained a First-Class degree. He moved to Swansea and in 2004 obtained a doctorate on the intellectual history of Benedetto Croce. Paci is currently the Co-Director of the Italian Cultural Centre Wales, the Italian Film Festival Cardiff and part of the executive board of Wales PEN Cymru. The past five years he has been teaching Italian Studies at Swansea and Cardiff University. He is a translingual poet, editor and translator into English, Welsh and Italian. Paci has published a number of essays, articles and poems in English and Italian. Among his translations are La Ragazza Carla/A Girl Named Carla by Elio Pagliarani (2006) and Bondo by Menna Elfyn (2021).

Susie Wildsmith is publishing editor at Parthian Books where she specialises in poetry and fiction and developing new writers. In recent years, she has visited the Guadalajara, Paris and London book fairs as well as being an International Publishing Fellow in Istanbul and a guest speaker with publishing conferences in Valencia and Galicia. Wildsmith has worked with authors, editors and translators from Turkey, the Basque Country, the Czech Republic, Italy, Germany, and Slovakia including two recent releases from 2021 Spanish National Poetry Award winner Miren Agur Meabe. She lives in south Wales where she also writes poetry and fiction as Susie Wild; her latest poetry collection is Windfalls (2021).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.