[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Avoiding the Pitfalls of Free Online Translation Tools AllBusiness.comThursday, April 7, 2022

‘Threat Dictionary’ showcases power of words and how they’re used to spread, combat fear - OregonLive - Dictionary

How tight or loose are you? Do you relate to Big Bird or Cookie Monster?

The answers to such questions have helped Stanford University professor Michele J. Gelfand understand how individuals and societies respond to common threats.

Gelfand and a team of University of Maryland computer scientists and psychologists now have taken the next step in this research, creating what they call a Threat Dictionary -- a data tool “designed to diagnose threatening language in any text that interests you.”

This might sound like an odd undertaking. But words have never been more contentious. Universities now try to protect students from “microaggressions.” TV shows open with warnings of “triggering language.”

A word is a word, no more or less. Its impact, however, depends on the person on the receiving end of it.

Whether certain words hit you like a hammer or a pillow -- that is, whether or how much they spark your brain’s “fear circuitry” -- is based on your experiences, education and exposure to popular culture, among other factors, the research suggests.

All of this, not surprisingly, is bound up with the hyperpolarization that dominates our politics.

“Adding just a single threat-related word to a tweet about COVID increased the expected retweet rate by 18%,” Sara Harrison writes for the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

How much will threat-related words affect you?

Gelfand, a professor of organizational behavior, created what she calls the Mindset Quiz to find out.

“How intensely you adhere to social norms has major implications for your life,” she writes in the introduction to the quiz. “This level of intensity falls on a spectrum from very loose to very tight. Knowing how tight or loose you are can help you understand yourself and others better.”

The quiz asks respondents to agree or disagree (on a scale) with statements such as: “I keep my emotions under control,” “I don’t like situations that are uncertain,” “I stick to the rules” and “I talk even when I know I shouldn’t.”

Through your answers, you will learn whether you’re an “order Muppet” or a “chaos Muppet.” (Uncertainty makes Big Bird anxious. Cookie Monster revels in mayhem.)

As for the 240-word Threat Dictionary -- with words ranging from “accidents” and “accusations” to “worry” and “worst” -- it can offer individual users some subtle insight and warning as they go about their online lives. You can copy-and-paste news articles and social-media posts into the tool to find out their “percent of threat language.” (For example: The top story on The Washington Post’s homepage Thursday morning, “Ukraine braces for assault in east; Russian talk of civilian killings intercepted,” comes in at 2%.)

But for the academics who created the Threat Dictionary, the usefulness is broader. The database’s algorithm, powered by information about perils the U.S. has faced over the past 100 years (stock-market crashes, wars, natural disasters, etc.), is designed to measure how our society responds to various kinds of threats.

“In all,” the researchers write in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), “the language of threats is a powerful tool that can inform researchers and policy makers on the public’s daily exposure to threatening language and make visible interesting societal patterns across American history.”

-- Douglas Perry

Wednesday, April 6, 2022

What is a data dictionary? - Dataconomy - Dictionary

Let’s start by answering the first thing that comes to mind: What is a data dictionary? A data dictionary, also known as a data definition matrix, contains comprehensive data about the company’s data, such as the definition of data elements, their meanings, and allowable values.

The dictionary, in essence, is a tool that allows you to convey business stakeholder needs in a way that allows your technical team to build a relational database or data structure faster. It aids in the prevention of project disasters, such as requiring information in a field for which a business stakeholder can’t reasonably be asked or expecting the wrong type of information in a field.

Table of Contents

Data dictionary definition

It is a compendium of terms, definitions, and attributes that apply to data elements in a database, information system, or study portion. It explains the denotation and connotation of data elements in the context of a project and offers recommendations on how they should be interpreted.

A data dictionary also includes data element metadata. The information included in a data dictionary may help you establish the scope and characteristics of data elements and the management that governs their usage and application.

Why is a data dictionary important?

Data dictionaries are helpful for a variety of reasons. To summarize, they have the following characteristics:

- Assist in eliminating project data inconsistencies.

- Define conventions that will be utilized throughout the project to avoid confusion.

- Provide consistency in data collection and usage across the team.

- Make it easier to analyze data.

- Enforce the use of data standards

What are data standards?

Standardized data follow standards. Data are gathered, recorded, and represented in accordance with standards. Standards provide a common framework for interpreting and utilizing data sets.

Researchers in different fields must use comparable standards to know that the manner their data are collected and described will be consistent across different projects. Using Data Standards as part of a well-designed dictionary might help make your research data more accessible. It will guarantee that data will be identifiable and usable by others.

The key elements of a data dictionary

It is a document that explains the meaning of each attribute in a data model. An attribute is a database position that contains information. For example, if we wanted to represent the articles on this website, we could have attributes for article title, author, category, and content.

It is generally organized in a spreadsheet. The spreadsheet contains rows for each attribute, with columns labeled for each piece of information relevant to the attribute.

A data dictionary has two essential elements:

- List of tables (or entities)

- List of columns (or fields, or attributes)

Let’s look at the most frequent components included in the dictionary.

- Attribute Name – A distinguishing name that is used to identify each feature.

- Optional/Required – Whether information is necessary for an attribute before a record may be stored is indicated by the presence of this checkbox.

- Attribute Type – How you determine what data will be included in a field is defined by this setting. Text, numeric, date/time, enumerated list, look-ups, booleans, and unique identifiers are just a few possible data types.

A data dictionary may include the origin of the data, the table or concept in which the attribute is found, and additional information about each component.

Types of data dictionary

It’s possible to split the dictionary into two categories:

- Active data dictionary

- Passive data dictionary

Active data dictionary

When the data definition language (DDL) changes the database object structure, it must be reflected in the data dictionary. The job of updating the data dictionary tables for any modifications is solely that of the database in which the data dictionary is located.The data dictionary is automatically updated if created in the same database. As a result, there will be no mismatch between the actual structure and the data dictionary details. An active data dictionary is current at the time of writing this book.

System Catalog

It’s a term used to describe several things: the System Catalog, system tables, data dictionary views, etc. The System Catalog is a collection of system tables or views incorporated into a database engine (DBMS) to allow users to access data in the database. It also contains information about security, logs, and health.

Moreover, System Catalog has some standards, such as Information Schema.

Information Schema

The Information Schema is a popular System Catalog standard defined by SQL-92. It’s a unique schema named information_schema with preconfigured system views and tables. Despite being a norm, each vendor implemented this standard to some degree, adding its tables and columns.

Some of the tables in information_schema:

- tables

- columns

- views

- referential_constraints

- table_constraints

Passive data dictionary

Some databases include a dictionary in a separate, independent database only used to store dictionary components. It’s often saved as XML, Excel files, or other file formats.

In this scenario, a concerted effort is required to keep the data dictionary in sync with the database objects. A passive dictionary is what you’re dealing with here. There’s a chance that the database objects and the data dictionary won’t match in this instance. This kind of DD has to be handled with great sensitivity.

The passive data dictionary is distinct from the database and must be updated manually or with specialized software whenever the database structure changes.

A passive dictionary might be implemented in a variety of ways:

- A document or spreadsheet

- Tools

- Data Catalogs

- Data integration/ETL metadata repositories

- Data modeling tools

- Custom implementations

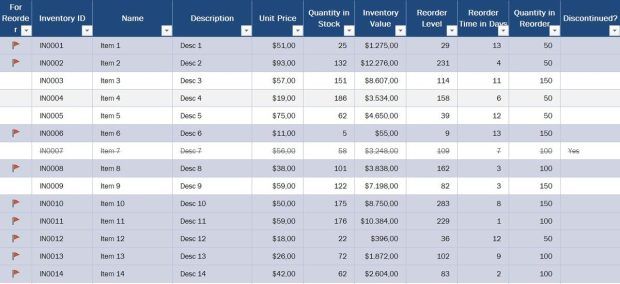

Data dictionary example

You’re undoubtedly asking how everything fits together.

Here’s a look at an inventory list, a basic example of a data dictionary.

As you can see, a dictionary organizes critical information about each attribute in a business-oriented way. It also groups information that may be found in multiple documents and specifications, making it more straightforward for your database developer to create or change a database that fulfills company demands.

Functions of data dictionary

A dictionary may be used for a variety of things. The following are some important uses:

Data dictionary in database systems (DBMS)

The information about data structures is kept in special formats in most relational database management systems – predefined tables or views that contain metadata for each component of a database, such as tables, columns, indexes, foreign keys, and constraints.

A data-driven tool generates reports based on the database schema, including all parts of the data model and programs.

Data modeling

Data models can be constructed with the data dictionary as a tool. This may be accomplished using specialized data modeling software or simply a spreadsheet or document. In this instance, the dictionary acts as a specification of entities and their fields, assisting business analysts, subject matter experts, and architects in collecting requirements and modeling the domain. You’ll develop and deploy a physical database and application following this document.

Documentation

It is also possible to use a data dictionary as a reference and cataloging tool for existing data assets – databases, spreadsheets, files, etc.

With a few formats and programs, you can achieve this:

- You may export read-only HTML or PDFs from a DBMS with database tools.

- Excel spreadsheets that have been manually created and maintained.

- The data modeling tools utilize reverse engineering.

- Database documentation tools.

- Metadata management/data catalogs

All of these efforts are for healthy database management.

What is database management?

A database’s data can be organized, stored, and retrieved using Database Management. A Database Administrator (DBA) may use various tools to manage data throughout its lifecycle.

Designing, implementing, and supporting stored data to increase its value is the goal of database management. There are different types of Database Management Systems.

- Centralized: All data resides in one system handled by a single person or team. Users go to that one system to access the information.

- Distributed: The organization wanted a highly scalable system that allowed data to be accessed quickly.

- Federated: Data is extracted from your existing source data without the requirement for extra storage or replication of original material. It combines numerous independent databases into a single colossal item. This style of Database Architecture is ideal for integration projects involving many different types of data. The following are examples of federated databases:

- Loosely Coupled: The relational structure of a component database is defined by its federated schema, which must be accessed via a multi-database language to access other component database systems.

- Tightly Coupled: Components use separate processes to generate and publish into a connected federal schema.

- Blockchain: A decentralized database architecture that allows you to keep track of your finances and other transactions securely.

Do you think your data dictionary will lead the road to successful database management?

'Threat dictionary' gauges cultural response to fear - Futurity: Research News - Dictionary

A new “threat dictionary” identifies language that shows when people feel threatened emotionally or physically and measures the magnitude of that perceived threat.

It’s an algorithmic tool that uses natural language processing to analyze texts.

One of the tool’s creators, Michele Gelfand, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, isn’t kidding when she asks if a person is an order Muppet or a chaos Muppet. She categorizes cultures and personalities on a spectrum from tight to loose and then examines how those differences affect nations, companies, families, and even individuals.

The two kinds of Muppets (first classified by Dahlia Lithwick in Slate in 2012) make for a pretty good proxy for this split.

Bert, Big Bird, and Kermit are rule followers. They tend to get anxious about unknown situations and aren’t big on spontaneous or rash decision-making. On the opposite end of the spectrum are Muppets like Ernie, Cookie Monster, and Animal. They’re more creative, but also quasi-unpredictable, and sometimes impulsive. Gelfand says she leans loose.

To find out what kind of Muppet you are, take her 20-question tight-loose quiz.

Beyond learning your Muppet-type, the loose-tight model provides a useful way to understand why culture and individuals land in different places on the continuum. The theory is deceptively simple. When groups experience chronic threats—think natural disasters, famine, invasions, or other hardships—stricter rules help them coordinate to survive. They tighten up, Gelfand explains. But groups that don’t experience chronic threat can afford to be more permissive.

Gelfand has been doing surveys and experiments across the globe to study the connection between threats and tightening. But she wanted a tool that could measure different kinds of threats over time and track how they correlate to cultural responses as well as how they predict political and economic shifts. Surprised to discover that no such tool existed, she decided to build one.

The resulting threat dictionary, created with researchers in computer science and psychology at the University of Maryland, College Park, appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The threat dictionary

Other researchers have developed dictionaries on other topics, but those efforts relied on people to come up with lists of words. Gelfand and her coauthors created their 240-word threat dictionary with text from Twitter, Wikipedia, and randomly chosen websites. Algorithms combed through the data, selecting words and plotting them on a graph, placing terms with similar meanings closer together.

The final list of words reads like an apocalyptic poem: attack, crisis, fear, frightening, injury, suffer, toxic, unstable.

The team then selected the words that most often co-occur across these platforms. They didn’t just choose synonyms, but terms that were often used in association with language that described threats. For instance, the term “unrest” is frequently used to describe an impending civil war. This approach was more comprehensive than purely human attempts and it allowed the dictionary to capture how people actually write about threats. The final list of words reads like an apocalyptic poem: attack, crisis, fear, frightening, injury, suffer, toxic, unstable.

The dictionary’s 240 words aren’t specific to any scenario and could be used to describe either interpersonal or external threats. They could just as soon describe the terror of a zombie uprising as the drama of a middle school dance. But they get at the underlying psychology of a society responding to threats that may be real or imagined.

The dictionary can also measure the relative magnitude of these threats and compare different levels of threat across texts and over time. That could help organizations, researchers, and societies understand their cultures and intentionally adapt to a given scenario.

Threats in US history

Gelfand and her colleagues tested the threat dictionary by feeding it information from three types of historical threats that the US has faced: violent conflicts like World War II, natural disasters like floods, and pathogens like COVID-19. Using a century’s worth of newspapers as well as stock market data, surveys that recorded attitudes toward immigrants, and language used in presidential speeches, the study examines how those threats predicted cultural, political, and economic shifts over the last 100 years.

Gelfand and her colleagues found that when people feel threatened either by a natural disaster, a disease outbreak, or a human enemy, they tighten up. Presidential approval rates go up, as do ethnocentrism and conservatism. But innovation suffers as cultural slack is picked up. During threat-heavy periods, fewer patents were filed and stock market prices were lower.

The researchers also showed that threatening language is contagious. Adding just a single threat-related word to a tweet about COVID increased the expected retweet rate by 18%.

Gelfand notes that there are exceptions to the threat-tightening link. She found that the US and other relatively loose countries have been slower to respond to the COVID pandemic and ultimately had more cases and deaths per capita. “Generally, loose cultures have had less threat in their histories,” she says. The United States hasn’t fought a war on its soil for over a century. “We haven’t had chronic invasions on our territory, so we’re not used to sacrificing a lot of liberty for constraint. It’s just not part of our cultural DNA.”

Other threats like 9/11 have caused Americans to tighten up in the past, but COVID-19 was different. The threat was invisible and abstract. And in some loose cultures, leaders ignored or downplayed the threat, which interrupted the typical tightening that naturally occurs.

Threatening language can manipulate us

On the other hand, Gelfand notes that leaders can manipulate threatening language in speeches or social media and can artificially tighten groups. In this way, a threat dictionary can help shine a light on how societies react when they feel threatened by identifying when and how often threats appear. Politicians, advertisements, and news reports often use fear to manipulate voters or rally people behind a cause.

“Culture’s invisible, but once we start measuring it, we can talk about it.”

But it’s hard to measure and study when and how much people feel threatened. “In cross-cultural psychology, we want to get as many measures as we can,” Gelfand says. That includes surveys, but also more unobtrusive tools like the dictionary, which she hopes will give researchers an empirical tool to evaluate this complex feeling more precisely and situate it within a larger social, political, and economic context.

It can also help elucidate how those cultural changes affect a company or nation by placing them in a larger social context. Researchers can correlate tightening or loosening with other indicators like stock market prices, public opinion polling, or investor behavior to see how threats affect different parts of society like the economy or immigration policy.

Looseness and tightness

The possible uses for the threat dictionary are vast, Gelfand says. It could be used to track when leaders inflate threats and which groups are labeled as dangerous. Researchers could analyze CEOs’ or officials’ speeches for threat mentions and compare them to fMRI images of what happens in peoples’ brains as they hear those terms.

Social media users could use it to be more conscious of how they’re participating in the spread of threatening messages and make choices about how much of that kind of language they want to see or what they want their kids to see. Gelfand’s threat barometer can be used to track how much threat one is exposed to on social media. The dictionary could also be combined with voting data to predict how a perceived threat might influence election results. Or it could examine how threatening language varies between different media outlets and how it affects the way they report the news.

Tightness versus looseness is a trade-off, Gelfand says, and it has to be balanced: “If you become extraordinarily tight or extraordinarily loose, that really causes a lot of problems.”

Unlike Muppets, who are entertaining because they rarely stray from their core characteristics, people and cultures can adapt to respond more effectively to difficult situations. Gelfand hopes the threat dictionary could help nations, companies, and individuals understand when they need to pivot. For more loose, chaotic types, this could mean tightening up to deal with a pandemic or war. For the tighter, orderly types, this could mean loosening up to create environments that encourage innovation and creative problem-solving.

The point, she says, isn’t that one type is better than the other. It’s the ability to titrate the right mix that really matters. “Culture’s invisible, but once we start measuring it, we can talk about it,” Gelfand says. “We can decide mindfully in what domains we want to tighten and in what domains we want to be loose.”

Source: Sara Harrison for Stanford University

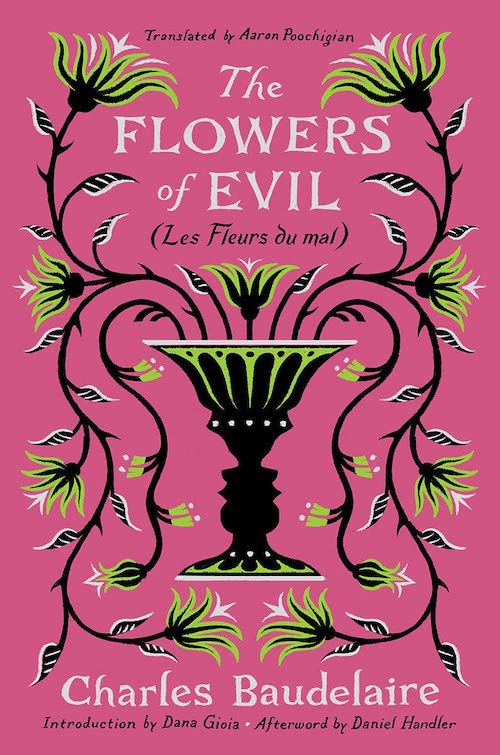

Mirror-Man: On Aaron Poochigian's Translation of Baudelaire - lareviewofbooks - Translation

A YOUNG MAN from the provinces arrives in the big city to make his reputation as a poet. He translates the work of others, composes beautifully crafted verse, and becomes a consummate chronicler of urban life. That is not Charles Baudelaire’s story. Baudelaire was born in Paris. As a teenager he began writing some of the poems that would evolve into Les Fleurs du mal, and later he translated Poe. The young man described is Aaron Poochigian, who was born in Grand Forks, North Dakota, trained as a Classicist, translated Sappho and Aristophanes, and writes about New York City (and beyond) like a jaundiced celebrator of its virtues and vices. And now he has translated one of his poetic forebears, Baudelaire (1821–’67). What Poochigian gives us in his Flowers of Evil are stylized, vigorous, clear, sturdy American poems, a recognizably 21st-century Baudelaire.

For a taste of his approach, consider Baudelaire’s introductory poem, “To the Reader” (“Au Lecteur”), taking the first stanza as a poetic core sample. Here is the late Richard Howard’s American Book Award–winning translation from 1982:

Stupidity, delusion, selfishness and lust

torment our bodies and possess our minds,

and we sustain our affable remorse

the way a beggar nourishes his lice.

Here is Walter Martin’s version from 1997:

Sin, stinting, senseless acts and sophistries

Pester the flesh and prey upon the mind;

We keep our stainless consciences maintained

Like indigents who fatten up their fleas.

Now Poochigian’s:

For all of us, greed, folly, error, vice

exhaust the body and obsess the soul,

and we keep feeding our congenial

remorse the same way vagrants nurse their lice.

Such remarkable variance of word choice. Until the fourth line one might almost assume the stanzas come from three different French poems. Only Poochigian uses “soul” and the four nouns in his first line. Howard and Poochigian choose “remorse,” while Martin changes the sense entirely to the awkward “stainless consciences.” There’s some confusion about the insect infestation: lice or fleas? Baudelaire gives us the indeterminant “vermine.” Howard selects “beggar” (singular) for Baudelaire’s “mendiants,” while Martin has the bureaucratic-sounding “indigents.” Poochigian wisely uses “vagrants,” which adds a suggestion of errancy and ephemerality. Best of all, Poochigian opens with the inclusive phrase “For all of us,” not those dutiful lists of nouns. He captures something quintessentially Baudelairean with the oxymoronic “congenial / remorse.” In his excellent introduction to Poochigian’s volume, Dana Gioia writes:

For Baudelaire, beauty exists in an endless dialectic between the spiritual and animalistic elements of human nature. The energy of that dialectic animates Baudelaire’s work. It also explains why his poetry is so difficult to interpret; it does not present static insights, but a dynamic relationship between contradictory forces.

That tense dance of opposites appears everywhere in Flowers of Evil. When it comes to sin and “transgression,” Baudelaire has an adolescent streak. You name it, he’ll try it: dope, whores, absinthe, Satan worship, any corruption of the human body and soul. He revels in offending bourgeois sensibilities. After his book was published in 1857, the poet, his publisher, and his printer all were prosecuted for offenses against public morals. More significantly, some of the poems still make for uncomfortable reading. In a poem Poochigian translates as “A Carcass” (“Une Charogne”), Baudelaire writes:

The blowflies in her bowels made a hum;

there also was a horde of seething

maggots flowing like a busy stream

across her ripped and living clothing.

And yet this bad boy was a strict formalist. In his “Note on the Translation,” Poochigian pledges his allegiance to that element of the work. The French originals are written largely in alexandrines, which he wisely has not attempted to replicate. Instead, he relies on English accentual-syllabics. Yes, he counts syllables but also pays attention to word stress and isn’t shy about using iambs. The effect is a more conversational reading of Baudelaire’s lines, with less stilted diction and syntax. To contemporary ears, Poochigian’s versions often sound “natural,” especially since his approach also leaves room for humor, as in these stanzas from “To One Who Is Too Cheerful” (“À Celle qui est trop gaie”):

Sometimes in green and pleasant places

to which I have lugged my great ennui,

I have suffered as, like irony,

rays of the sun chewed me to pieces.

And then the springtime greenery

so demoralized my heart

that I have ripped a flower apart

to punish Nature’s pomposity.

For all his outrageousness, Baudelaire remains a moralist. Yvor Winters observed that his poems often conform to a common 19th-century poetic structure: “[T]he account of an action, a situation, or an object followed by a moral tag.” Among the poems Winters prized above all others in any language was Baudelaire’s “Le Jeu,” translated by Poochigian as “Gambling.” He sets the scene: “pale, old courtesans” sit around the “green felt” listening to “the garish stones / and metals tinkle.” They are spectators at the roulette table, watching the “poets, who waste their sweat and earnings there.” Baudelaire’s speaker in turn watches the courtesans, “palsied by accursed diseases,” who watch the gamblers. The scene unfolds before his “visionary eyes,” as in a dream. Here is the final stanza:

I shuddered at my envy of that lot

dashing so rashly into the abyss.

Drunk on the blood down there, they choose to set

pain over death, Hell over nothingness.

Poochigian’s Baudelaire is evidence of an ongoing Golden Age of Translation from many languages, including Italian, German, and Russian. It’s a good time to be a reader. We obdurately monolingual Americans, of course, have much to lose, especially in the work of so musical a poet as Baudelaire. Our debt to translators like Poochigian, who are comparably sensitive to both sound and sense, is enormous. In his translation note, Poochigian tells us he has attempted to replicate “the almost magical effect of the originals and to render beautiful in English Baudelaire’s nontraditional beauties — disease, vice, intoxication, and decay.”

It helps that Poochigian is one of our finest young poets. A Baudelairean strain runs through his own work. A poem in his most recent collection, American Divine, is titled “The Satanists”:

hunkered with candles

and all the goodies

demons enjoy,

in the hopefully hexed

and totally scary

dead lot next

to the cemetery.

And here’s a memorable dog in “My Political Poem,” from the earlier Manhattanite: “So cute — one-eyed, scab-nostriled, stumpy-tailed.” Appealing and grotesque, a combination in which his French forebear specialized. Present in Poochigian’s poems, including the translations, is what Baudelaire elsewhere calls “the heavy darkness of communal and day-to-day existence,” but made lighter, funnier, bouncier, with the gravitas muted. W. S. Di Piero has written of Thom Gunn: “He admired Ben Jonson and Baudelaire because their little-furnace forms — those clocking, rhyming meters — could contain fevered appetites and personal anarchy.” That’s Poochigian and his calibrated tension between tidy form and riot: “furnace forms,” with equal emphasis on both words.

Earlier I quoted Poochigian’s opening stanza from “To the Reader.” Here is his version of the poem’s final stanza, including Baudelaire’s most familiar lines:

Boredom! Moist-eyed, he dreams, while pulling on

A hookah pipe, of guillotine-cleft necks.

You, reader, know this tender freak of freaks —

Hypocrite reader — mirror-man — my twin!

Poochigian’s rendering of “mon semblable” as “mirror-man” is inspired. As Gioia points out, the poem is written in the first-person plural, blurring the identities of poet and reader. All of us are implicated.

¤

Patrick Kurp is a writer living in Houston and the author of the literary blog Anecdotal Evidence.

Tuesday, April 5, 2022

Text-to-911 translation now available - Seymour Tribune - Translation

The Indiana Statewide 911 Board, in collaboration with INdigital and the state treasurer’s office, recently announced another tool that enhances communications between non-English-speaking citizens and emergency services.

Since 2019, dispatchers at all of Indiana’s public safety answering points have had access to Language Line, which provides voice translating services for 911 callers. Over the past three years, Indiana telecommunicators have used voice translation services for nearly 70 of the more than 250 languages available.

Spanish is the most frequently translated language used, comprising of 91% of the translation calls. Marion, Elkhart, Allen, White and Tippecanoe counties are the top five users of the system.

Speaking at the Metropolitan Emergency Services Agency on March 30, Treasurer Kelly Mitchell, chairwoman of the state 911 board, unveiled significant enhancements to the Text-to-911 system.

Citizens can now send text messages in their native language directly to 911 for help, and they will be automatically translated for the dispatcher. As the dispatcher responds, it will be automatically translated back into the native language of the sender. There are 108 languages available for Text-to-911 translation.

The Jackson County Sheriff’s Department is among those able to translate other languages through the 911 texting system, according to a news release from the department.

“Text-to-911 enables direct access to emergency services for those who are deaf or speaking-impaired, having a medical emergency that prevents them from being able to speak or in a situation where making a voice call would put them in danger,” Mitchell said.

“We’ve already seen the benefits of texting to 911,” she said. “It allows people in sensitive situations to communicate with law enforcement, and now, we are removing the language barriers to those services.”

In 2014, Indiana was one of the first states to begin implementing Text-to-911, and by 2016, all 92 counties had the capability.

As a result, Indiana telecommunicators have processed more than 1.3 million inbound and outbound text sessions.

“With technology constantly evolving, this upgrade shows why Indiana is on the forefront in providing 911 services to our non-English-speaking citizens,” said Ed Reuter, executive director of the state’s 911 board. “This new translation upgrade will help bridge the communication gap and speed up sending emergency services when every second counts.”

Mark Grady, chief executive officer of INdigital, said his company works to improve 911 service every day.

“Strong state programs like Indiana lead the nation with good legislation, targeted funding and letting us build better systems,” he said. “Our goal is for everyone to have access to 911 when they need it most. Bridging language barriers and providing more ways to communicate are essential in today’s world.”

The Mindful Dictionary:A is for Appreciate - Maldon and Burnham Standard - Dictionary

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

The Mindful Dictionary:A is for Appreciate Maldon and Burnham Standard