A new “threat dictionary” identifies language that shows when people feel threatened emotionally or physically and measures the magnitude of that perceived threat.

It’s an algorithmic tool that uses natural language processing to analyze texts.

One of the tool’s creators, Michele Gelfand, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, isn’t kidding when she asks if a person is an order Muppet or a chaos Muppet. She categorizes cultures and personalities on a spectrum from tight to loose and then examines how those differences affect nations, companies, families, and even individuals.

The two kinds of Muppets (first classified by Dahlia Lithwick in Slate in 2012) make for a pretty good proxy for this split.

Bert, Big Bird, and Kermit are rule followers. They tend to get anxious about unknown situations and aren’t big on spontaneous or rash decision-making. On the opposite end of the spectrum are Muppets like Ernie, Cookie Monster, and Animal. They’re more creative, but also quasi-unpredictable, and sometimes impulsive. Gelfand says she leans loose.

To find out what kind of Muppet you are, take her 20-question tight-loose quiz.

Beyond learning your Muppet-type, the loose-tight model provides a useful way to understand why culture and individuals land in different places on the continuum. The theory is deceptively simple. When groups experience chronic threats—think natural disasters, famine, invasions, or other hardships—stricter rules help them coordinate to survive. They tighten up, Gelfand explains. But groups that don’t experience chronic threat can afford to be more permissive.

Gelfand has been doing surveys and experiments across the globe to study the connection between threats and tightening. But she wanted a tool that could measure different kinds of threats over time and track how they correlate to cultural responses as well as how they predict political and economic shifts. Surprised to discover that no such tool existed, she decided to build one.

The resulting threat dictionary, created with researchers in computer science and psychology at the University of Maryland, College Park, appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The threat dictionary

Other researchers have developed dictionaries on other topics, but those efforts relied on people to come up with lists of words. Gelfand and her coauthors created their 240-word threat dictionary with text from Twitter, Wikipedia, and randomly chosen websites. Algorithms combed through the data, selecting words and plotting them on a graph, placing terms with similar meanings closer together.

The final list of words reads like an apocalyptic poem: attack, crisis, fear, frightening, injury, suffer, toxic, unstable.

The team then selected the words that most often co-occur across these platforms. They didn’t just choose synonyms, but terms that were often used in association with language that described threats. For instance, the term “unrest” is frequently used to describe an impending civil war. This approach was more comprehensive than purely human attempts and it allowed the dictionary to capture how people actually write about threats. The final list of words reads like an apocalyptic poem: attack, crisis, fear, frightening, injury, suffer, toxic, unstable.

The dictionary’s 240 words aren’t specific to any scenario and could be used to describe either interpersonal or external threats. They could just as soon describe the terror of a zombie uprising as the drama of a middle school dance. But they get at the underlying psychology of a society responding to threats that may be real or imagined.

The dictionary can also measure the relative magnitude of these threats and compare different levels of threat across texts and over time. That could help organizations, researchers, and societies understand their cultures and intentionally adapt to a given scenario.

Threats in US history

Gelfand and her colleagues tested the threat dictionary by feeding it information from three types of historical threats that the US has faced: violent conflicts like World War II, natural disasters like floods, and pathogens like COVID-19. Using a century’s worth of newspapers as well as stock market data, surveys that recorded attitudes toward immigrants, and language used in presidential speeches, the study examines how those threats predicted cultural, political, and economic shifts over the last 100 years.

Gelfand and her colleagues found that when people feel threatened either by a natural disaster, a disease outbreak, or a human enemy, they tighten up. Presidential approval rates go up, as do ethnocentrism and conservatism. But innovation suffers as cultural slack is picked up. During threat-heavy periods, fewer patents were filed and stock market prices were lower.

The researchers also showed that threatening language is contagious. Adding just a single threat-related word to a tweet about COVID increased the expected retweet rate by 18%.

Gelfand notes that there are exceptions to the threat-tightening link. She found that the US and other relatively loose countries have been slower to respond to the COVID pandemic and ultimately had more cases and deaths per capita. “Generally, loose cultures have had less threat in their histories,” she says. The United States hasn’t fought a war on its soil for over a century. “We haven’t had chronic invasions on our territory, so we’re not used to sacrificing a lot of liberty for constraint. It’s just not part of our cultural DNA.”

Other threats like 9/11 have caused Americans to tighten up in the past, but COVID-19 was different. The threat was invisible and abstract. And in some loose cultures, leaders ignored or downplayed the threat, which interrupted the typical tightening that naturally occurs.

Threatening language can manipulate us

On the other hand, Gelfand notes that leaders can manipulate threatening language in speeches or social media and can artificially tighten groups. In this way, a threat dictionary can help shine a light on how societies react when they feel threatened by identifying when and how often threats appear. Politicians, advertisements, and news reports often use fear to manipulate voters or rally people behind a cause.

“Culture’s invisible, but once we start measuring it, we can talk about it.”

But it’s hard to measure and study when and how much people feel threatened. “In cross-cultural psychology, we want to get as many measures as we can,” Gelfand says. That includes surveys, but also more unobtrusive tools like the dictionary, which she hopes will give researchers an empirical tool to evaluate this complex feeling more precisely and situate it within a larger social, political, and economic context.

It can also help elucidate how those cultural changes affect a company or nation by placing them in a larger social context. Researchers can correlate tightening or loosening with other indicators like stock market prices, public opinion polling, or investor behavior to see how threats affect different parts of society like the economy or immigration policy.

Looseness and tightness

The possible uses for the threat dictionary are vast, Gelfand says. It could be used to track when leaders inflate threats and which groups are labeled as dangerous. Researchers could analyze CEOs’ or officials’ speeches for threat mentions and compare them to fMRI images of what happens in peoples’ brains as they hear those terms.

Social media users could use it to be more conscious of how they’re participating in the spread of threatening messages and make choices about how much of that kind of language they want to see or what they want their kids to see. Gelfand’s threat barometer can be used to track how much threat one is exposed to on social media. The dictionary could also be combined with voting data to predict how a perceived threat might influence election results. Or it could examine how threatening language varies between different media outlets and how it affects the way they report the news.

Tightness versus looseness is a trade-off, Gelfand says, and it has to be balanced: “If you become extraordinarily tight or extraordinarily loose, that really causes a lot of problems.”

Unlike Muppets, who are entertaining because they rarely stray from their core characteristics, people and cultures can adapt to respond more effectively to difficult situations. Gelfand hopes the threat dictionary could help nations, companies, and individuals understand when they need to pivot. For more loose, chaotic types, this could mean tightening up to deal with a pandemic or war. For the tighter, orderly types, this could mean loosening up to create environments that encourage innovation and creative problem-solving.

The point, she says, isn’t that one type is better than the other. It’s the ability to titrate the right mix that really matters. “Culture’s invisible, but once we start measuring it, we can talk about it,” Gelfand says. “We can decide mindfully in what domains we want to tighten and in what domains we want to be loose.”

Source: Sara Harrison for Stanford University

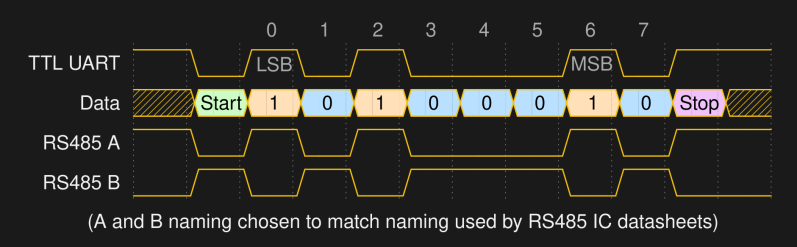

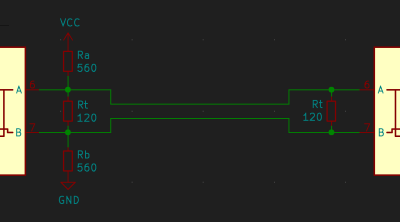

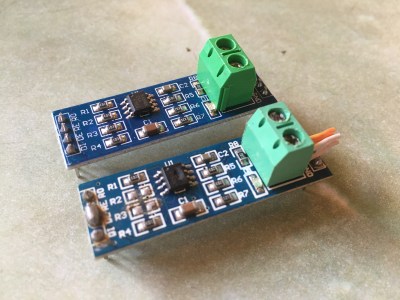

![Quote saying "[...] lack of ground can result in high common-mode offset voltage on one of the ends. "](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/hadqib_rs485_101_6.png?w=400) “Do you need a ground connection for a RS485 link?” is a hotly debated question, just like “do I need to tie my USB port shield to ground”. You will see a lot of people say that a ground reference isn’t technically needed – after all, it’s a differential signal, and at most, shielding could be called for. This will generally work, even! However, lack of ground can result in high common-mode (relative to ground) offset voltage on one of the ends, and while RS485 transceiver ICs can handle quite a bit of that, it can cause issues depending on the kind of devices in your network.

“Do you need a ground connection for a RS485 link?” is a hotly debated question, just like “do I need to tie my USB port shield to ground”. You will see a lot of people say that a ground reference isn’t technically needed – after all, it’s a differential signal, and at most, shielding could be called for. This will generally work, even! However, lack of ground can result in high common-mode (relative to ground) offset voltage on one of the ends, and while RS485 transceiver ICs can handle quite a bit of that, it can cause issues depending on the kind of devices in your network. With this knowledge of RS485, you won’t just be able to gain control of more and more powerful devices out there, you will also figure out some fun things that will help you in other areas. For instance, you don’t have to put UART-like communications through a RS485 transceiver, you can simply use it for transmitting the state of a GPIO in a noisy environment. Or you can use an RS485 transmitter to dramatically extend range and stability of WS2812 LED protocol communications, especially when you have high-voltage lines running close to your LED strips.

With this knowledge of RS485, you won’t just be able to gain control of more and more powerful devices out there, you will also figure out some fun things that will help you in other areas. For instance, you don’t have to put UART-like communications through a RS485 transceiver, you can simply use it for transmitting the state of a GPIO in a noisy environment. Or you can use an RS485 transmitter to dramatically extend range and stability of WS2812 LED protocol communications, especially when you have high-voltage lines running close to your LED strips.