A YOUNG MAN from the provinces arrives in the big city to make his reputation as a poet. He translates the work of others, composes beautifully crafted verse, and becomes a consummate chronicler of urban life. That is not Charles Baudelaire’s story. Baudelaire was born in Paris. As a teenager he began writing some of the poems that would evolve into Les Fleurs du mal, and later he translated Poe. The young man described is Aaron Poochigian, who was born in Grand Forks, North Dakota, trained as a Classicist, translated Sappho and Aristophanes, and writes about New York City (and beyond) like a jaundiced celebrator of its virtues and vices. And now he has translated one of his poetic forebears, Baudelaire (1821–’67). What Poochigian gives us in his Flowers of Evil are stylized, vigorous, clear, sturdy American poems, a recognizably 21st-century Baudelaire.

For a taste of his approach, consider Baudelaire’s introductory poem, “To the Reader” (“Au Lecteur”), taking the first stanza as a poetic core sample. Here is the late Richard Howard’s American Book Award–winning translation from 1982:

Stupidity, delusion, selfishness and lust

torment our bodies and possess our minds,

and we sustain our affable remorse

the way a beggar nourishes his lice.

Here is Walter Martin’s version from 1997:

Sin, stinting, senseless acts and sophistries

Pester the flesh and prey upon the mind;

We keep our stainless consciences maintained

Like indigents who fatten up their fleas.

Now Poochigian’s:

For all of us, greed, folly, error, vice

exhaust the body and obsess the soul,

and we keep feeding our congenial

remorse the same way vagrants nurse their lice.

Such remarkable variance of word choice. Until the fourth line one might almost assume the stanzas come from three different French poems. Only Poochigian uses “soul” and the four nouns in his first line. Howard and Poochigian choose “remorse,” while Martin changes the sense entirely to the awkward “stainless consciences.” There’s some confusion about the insect infestation: lice or fleas? Baudelaire gives us the indeterminant “vermine.” Howard selects “beggar” (singular) for Baudelaire’s “mendiants,” while Martin has the bureaucratic-sounding “indigents.” Poochigian wisely uses “vagrants,” which adds a suggestion of errancy and ephemerality. Best of all, Poochigian opens with the inclusive phrase “For all of us,” not those dutiful lists of nouns. He captures something quintessentially Baudelairean with the oxymoronic “congenial / remorse.” In his excellent introduction to Poochigian’s volume, Dana Gioia writes:

For Baudelaire, beauty exists in an endless dialectic between the spiritual and animalistic elements of human nature. The energy of that dialectic animates Baudelaire’s work. It also explains why his poetry is so difficult to interpret; it does not present static insights, but a dynamic relationship between contradictory forces.

That tense dance of opposites appears everywhere in Flowers of Evil. When it comes to sin and “transgression,” Baudelaire has an adolescent streak. You name it, he’ll try it: dope, whores, absinthe, Satan worship, any corruption of the human body and soul. He revels in offending bourgeois sensibilities. After his book was published in 1857, the poet, his publisher, and his printer all were prosecuted for offenses against public morals. More significantly, some of the poems still make for uncomfortable reading. In a poem Poochigian translates as “A Carcass” (“Une Charogne”), Baudelaire writes:

The blowflies in her bowels made a hum;

there also was a horde of seething

maggots flowing like a busy stream

across her ripped and living clothing.

And yet this bad boy was a strict formalist. In his “Note on the Translation,” Poochigian pledges his allegiance to that element of the work. The French originals are written largely in alexandrines, which he wisely has not attempted to replicate. Instead, he relies on English accentual-syllabics. Yes, he counts syllables but also pays attention to word stress and isn’t shy about using iambs. The effect is a more conversational reading of Baudelaire’s lines, with less stilted diction and syntax. To contemporary ears, Poochigian’s versions often sound “natural,” especially since his approach also leaves room for humor, as in these stanzas from “To One Who Is Too Cheerful” (“À Celle qui est trop gaie”):

Sometimes in green and pleasant places

to which I have lugged my great ennui,

I have suffered as, like irony,

rays of the sun chewed me to pieces.

And then the springtime greenery

so demoralized my heart

that I have ripped a flower apart

to punish Nature’s pomposity.

For all his outrageousness, Baudelaire remains a moralist. Yvor Winters observed that his poems often conform to a common 19th-century poetic structure: “[T]he account of an action, a situation, or an object followed by a moral tag.” Among the poems Winters prized above all others in any language was Baudelaire’s “Le Jeu,” translated by Poochigian as “Gambling.” He sets the scene: “pale, old courtesans” sit around the “green felt” listening to “the garish stones / and metals tinkle.” They are spectators at the roulette table, watching the “poets, who waste their sweat and earnings there.” Baudelaire’s speaker in turn watches the courtesans, “palsied by accursed diseases,” who watch the gamblers. The scene unfolds before his “visionary eyes,” as in a dream. Here is the final stanza:

I shuddered at my envy of that lot

dashing so rashly into the abyss.

Drunk on the blood down there, they choose to set

pain over death, Hell over nothingness.

Poochigian’s Baudelaire is evidence of an ongoing Golden Age of Translation from many languages, including Italian, German, and Russian. It’s a good time to be a reader. We obdurately monolingual Americans, of course, have much to lose, especially in the work of so musical a poet as Baudelaire. Our debt to translators like Poochigian, who are comparably sensitive to both sound and sense, is enormous. In his translation note, Poochigian tells us he has attempted to replicate “the almost magical effect of the originals and to render beautiful in English Baudelaire’s nontraditional beauties — disease, vice, intoxication, and decay.”

It helps that Poochigian is one of our finest young poets. A Baudelairean strain runs through his own work. A poem in his most recent collection, American Divine, is titled “The Satanists”:

hunkered with candles

and all the goodies

demons enjoy,

in the hopefully hexed

and totally scary

dead lot next

to the cemetery.

And here’s a memorable dog in “My Political Poem,” from the earlier Manhattanite: “So cute — one-eyed, scab-nostriled, stumpy-tailed.” Appealing and grotesque, a combination in which his French forebear specialized. Present in Poochigian’s poems, including the translations, is what Baudelaire elsewhere calls “the heavy darkness of communal and day-to-day existence,” but made lighter, funnier, bouncier, with the gravitas muted. W. S. Di Piero has written of Thom Gunn: “He admired Ben Jonson and Baudelaire because their little-furnace forms — those clocking, rhyming meters — could contain fevered appetites and personal anarchy.” That’s Poochigian and his calibrated tension between tidy form and riot: “furnace forms,” with equal emphasis on both words.

Earlier I quoted Poochigian’s opening stanza from “To the Reader.” Here is his version of the poem’s final stanza, including Baudelaire’s most familiar lines:

Boredom! Moist-eyed, he dreams, while pulling on

A hookah pipe, of guillotine-cleft necks.

You, reader, know this tender freak of freaks —

Hypocrite reader — mirror-man — my twin!

Poochigian’s rendering of “mon semblable” as “mirror-man” is inspired. As Gioia points out, the poem is written in the first-person plural, blurring the identities of poet and reader. All of us are implicated.

¤

Patrick Kurp is a writer living in Houston and the author of the literary blog Anecdotal Evidence.

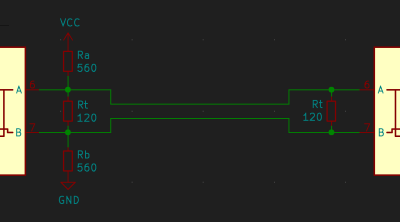

![Quote saying "[...] lack of ground can result in high common-mode offset voltage on one of the ends. "](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/hadqib_rs485_101_6.png?w=400) “Do you need a ground connection for a RS485 link?” is a hotly debated question, just like “do I need to tie my USB port shield to ground”. You will see a lot of people say that a ground reference isn’t technically needed – after all, it’s a differential signal, and at most, shielding could be called for. This will generally work, even! However, lack of ground can result in high common-mode (relative to ground) offset voltage on one of the ends, and while RS485 transceiver ICs can handle quite a bit of that, it can cause issues depending on the kind of devices in your network.

“Do you need a ground connection for a RS485 link?” is a hotly debated question, just like “do I need to tie my USB port shield to ground”. You will see a lot of people say that a ground reference isn’t technically needed – after all, it’s a differential signal, and at most, shielding could be called for. This will generally work, even! However, lack of ground can result in high common-mode (relative to ground) offset voltage on one of the ends, and while RS485 transceiver ICs can handle quite a bit of that, it can cause issues depending on the kind of devices in your network. With this knowledge of RS485, you won’t just be able to gain control of more and more powerful devices out there, you will also figure out some fun things that will help you in other areas. For instance, you don’t have to put UART-like communications through a RS485 transceiver, you can simply use it for transmitting the state of a GPIO in a noisy environment. Or you can use an RS485 transmitter to dramatically extend range and stability of WS2812 LED protocol communications, especially when you have high-voltage lines running close to your LED strips.

With this knowledge of RS485, you won’t just be able to gain control of more and more powerful devices out there, you will also figure out some fun things that will help you in other areas. For instance, you don’t have to put UART-like communications through a RS485 transceiver, you can simply use it for transmitting the state of a GPIO in a noisy environment. Or you can use an RS485 transmitter to dramatically extend range and stability of WS2812 LED protocol communications, especially when you have high-voltage lines running close to your LED strips.