Saturday, November 27, 2021

Translation: What Happened When My Health Code Turned Yellow - China Digital Times - Translation

China’s “zero-Covid” policy relies heavily on mobile phone apps that display a health code in one of three “traffic light” colors: red, yellow, or green. Users install the apps via WeChat or Alipay, enter their personal, medical and travel information, and the apps generate a color code that informs users whether they are at low risk and can travel freely (green), are at medium risk and need to self-isolate for 7-14 days and be tested (yellow), or are at high risk and need to self-isolate or quarantine for 14 days and be tested (red).

An individual’s health app color code can change over time, depending on his or her travel history, contact history, biometric data, and local conditions. An analysis by The New York Times found that the Alipay health code app was also capable of sending individuals’ locations, city names and identifying code numbers to the police.

The recent expansion of yellow codes based on “spatial-temporal proximity” has turned daily life upside-down, forcing thousands into lockdown simply for being within 800 meters of someone whose health code is anything but green.

In this translated WeChat post, which appears to have leaked from a private account, “Gentle Moss” (温良的青苔) chronicles how all the caution in the world could not save him from a yellow health code, and why standing in line to get tested may be a fate worse than quarantine:

Since returning to Xi’an from Tibet on September 3, the majority of my movement has been limited to a radius of a few hundred meters from my apartment. I go downstairs for mixian, then come right back up and continue writing. On rare occasions I might pick up a package along the way. The farthest I go is to see my dad. That requires a subway ride and a walk. Whenever I go, I maintain social distance and wear a mask, and I always walk all the way down to the first subway car. I do all this out of habit. Plus, my sleep schedule is the opposite of most people’s. When everyone else is working, I’m sleeping, and vice versa, so I’m never out during rush hour.

With all this precaution, I didn’t take a single COVID-19 test for this trip to Tibet. I made it through every inspection point thanks to my green health code, my travel code, and a little sweet-talking. Saying the right things to the inspectors always helps, as well. They just took my temperature and let me go.

I was really careful. During the day, I was on my motorcycle, so of course I didn’t come into contact with anyone, and I put my mask on before going into my hotel at night. They only let me stay after I’d gone through strict COVID-19 protocols.

In spite of all this, a few days ago my health code turned yellow. I also got two text messages, informing me that I had passed through a high-risk area and was now required to quarantine at home. The last sentences really caught my attention: “Your health code will be continuously updated as pandemic conditions change. Please stay tuned for updates.”

I live in Xi’an’s Yanta District, just a few kilometers from Ci’en Temple (Giant Wild Goose Pagoda) where Master Xuanzang translated the Buddhist scriptures. It just so happened that those tourists from Shanghai—the ones who made pandemonium in northwest China—had visited Giant Wild Goose Pagoda. All of a sudden, the people of Yanta became China’s biggest pariahs. All around Xi’an, if you had a Shaanxi license plate, the traffic police would turn you away—“Go wherever you want, just not here.”

Just like having a Hubei plate last year.

This was a huge blow to me personally, because I have to leave my apartment complex in order to eat. But if I did, I wouldn’t be able to get back in. One look at my yellow health code, and security would stop me. There was absolutely nothing I could do.

The texts were sent from a number that was not a cell phone number. I couldn’t text it or call back. After my code turned yellow, all the stuff that used to be there, like the government services portal, neighborhood services, COVID-19 testing site information…they were all gone. There was just a big “code yellow” icon and some generic safety messages.

It didn’t make any sense to me. They should have at least left the testing site portal, no?

At any rate, that barren screen and those stern warnings made me feel like I’d been whisked away to a desert island. Sure, outside my window cars whizzed by and the hustle and bustle of normal life continued. But those people were all green. They could go wherever they pleased. Me? I was stuck. I couldn’t go to the grocery store, restaurants, movie theaters. I couldn’t ride the subway or any public transportation. And if I left my apartment, I wouldn’t even be allowed back in…

But that wasn’t even the biggest issue. My biggest issue was that when I told my family and friends that I wouldn’t be able to get back home if I went to the get-together we had planned for the following Monday, they all begged me to go get tested.

I didn’t want to go.

Of course, my reasoning was based on the fact that I had complete knowledge of my travel history, my strong sense of self-discipline, and the prevention measures I followed. Never in a million years would I allow myself to be running around if I wasn’t feeling well. One of my biggest fears is causing trouble for my family, friends, and the people around me. I never ask favors if I don’t absolutely have to.

Plus, the notice was clear: I was to remain quarantined at home. Fine, then, just let me stay at my office and eat takeout every day…

I believe testing is an important epidemic control measure, a necessary one. But I’m really confused about who should be getting tested and how the tests are done.

The free tests are run in batches of ten. That is, ten throat swabs (or nasal swabs) are put into the same machine, and if anyone in the group tests positive, then all ten people will be notified or tracked down, and measures will be taken.

You can also pay for a test. They cost 60 yuan (in the Chang’an District). The line for those is so long, you can’t see where it begins or ends.

When I asked one of the hundreds of people in line, it turned out that they all had yellow health codes. They had no choice. But everyone was crowded together. What happened to social distancing? If someone in line was positive, how many people would they infect?

That scene filled me with dread. I only spoke with the very last person in line, and only from a few steps away. As soon as I got my answer, I walked around them and left.

Terrifying.

This was a big reason why I didn’t want to get tested. My goal was to prove that I’m healthy, but in the process of attaining that proof, I could get infected.

Since I know that I personally am safe, I intuitively disagree with compulsory, universal testing.

It’s a feeling that comes from deep within. Perhaps this is what people call “civil disobedience.” Of course, I know I’m nothing but a lowly “denizen” (but I’ve always considered myself a citizen, at least a citizen of the world).

This is just my personal feeling. It’s really not a wise thing to write about in today’s China, but the feeling is real.

When friends and family all tell you to follow orders from the authorities, it’s a tremendous amount of pressure. (Only three people in my life supported my decision to follow my own thinking. Thank you to Brother Nian for being the most resolute supporter of them all.)

When compliance becomes a collective choice, when it affects all aspects of your life, and non-compliance introduces an immense amount of real, practical challenges, the dynamic becomes one of great power disparity, like trying to prop up a mountain with a twig.

I know the people in my life just want what’s best for me, honestly. They know I’m a staunch liberalist and a nonconformist, so they worry these problems I’ve brought on myself might break my spirit, that my inner torment will bring me all kinds of real-world strife.

So they plead with me to compromise. “It’s not like they’re asking you to get a shot,” they say. “Just go get it done, and it will be over. And once you do, you’ll be able to go wherever you want. Don’t make yourself suffer like this.” These words are really persuasive.

I actually did plan to give in, at first.

I’m a living, breathing human, after all. I need to eat and drink. I need to see my family and friends, go to the movies, go to the book store—and no one would let me in. I’d have a breakdown. I just can’t imagine how a normal, healthy individual could be labeled a threat by “big data” for nothing more than living in an area that a COVID-positive person once passed through. It’s like the plot from a sci-fi film I saw years ago, now becoming my reality.

I can’t just stop visiting my dad. But if they don’t let me into his complex, what am I going to do, force my way in? Security would kick me right out. The police would put me in a black cell. I can’t beat them. Actually, the moment my health code turned yellow, my ability to go to the supermarket or the theater wasn’t the first thing on my mind. I was worried the authorities would give me a call, then come and take me away.

Reality justified my worries. Yesterday afternoon I read that your code will turn red if you fail to get tested after two notices. You can imagine the consequences.

So, why not go get tested, I thought to myself. Otherwise, then what?

Yesterday morning, I turned on my motorcycle, took out my phone, and clicked the link Brother Dao sent me to find the closest testing site. I let my bike idle for a full three minutes as I paced back and forth in the late autumn morning air, thinking to myself, “You always tell people to stay strong and not give in, to be themselves. How could you let yourself give up so quickly? Is this really as far as you’re able to go?”

After five or six minutes of pacing, I turned the bike off and went back upstairs.

Sitting on my balcony looking out the window, I thought of my friends in the civil service: If I was under this much pressure for this small matter, they’d probably lose their jobs if they made the same decision as me. Their entire futures would be affected. Then what would they do?

In that moment, I really felt for them: You all have it rough. Really. When your survival depends on it, how could you choose anything but surrender?

But even if I got tested, would it really solve all my problems? The way I see it, not necessarily.

A good friend of mine, Youcai (pseudonym), drove to a certain city in the north yesterday. The traffic police saw his Shaanxi license plate and turned him away. Youcai explained that he’d been tested, but the police didn’t accept his test, which was from five days ago. The police told him the test had to be taken within 48 hours (the government standard is 15 days) and told him he had to go back. “Why didn’t you post this information online?” Youcai asked. “I’ve driven hundreds of kilometers.”

The officer was very polite. “Apologies,” he replied, “We just enforce the rules. We don’t control what gets posted online.”

I suspect the reason they don’t post it is because, according to the government, test results are valid for 15 days. But as is often the case when central government regulations get enforced at the local level, those 15 days became 48 hours. This is institutional inertia: as information travels through the bureaucracy, from the center down to the grassroots, recommendations become mandatory.

And for what?

It may seem like they’re just strictly enforcing the rules, but each local government acts like “the railway police—each in charge of one section,” so to speak.

Youcai had no choice but to turn around. On the way back, coming through a certain city to the west, the situation was much different. Not once was he stopped and asked to show his test results.

“If I really was a carrier,” Youcai said, “I could have just waltzed right in, you know?”

So you see, it’s either overreaction, or negligence. This is how things stand.

A few days ago, China Central Television’s official Douyin account reported that as of November 9, South Korea will officially adopt a policy of “living with COVID-19,” meaning they will treat it like the flu or any other infectious disease. An army of idiots mocked South Korea in the comments. It saddened me to see it—over 100 years, and not an inch of progress.

Should we be fighting the pandemic? Of course we should. We actually did a great job of it early on, when physical distancing drove infection numbers down. Of course, there were also a lot of infuriating situations, like barring people’s doors and apartment units. That’s why we had the Gong Lady’s performance.

But as the pandemic evolves around the world, a lot of initially hard-hit countries have begun to normalize. At Euro 2020 this summer, Chinese gazed in awe not only at the matches, but also at the seas of people allowed to gather at such huge events—during a global pandemic. And not only that, after the competition ended, there were no large-scale outbreaks. It proved Zhang Wenhong’s earlier prediction correct:

Our success in the fight against the pandemic has been achieved mainly through non-medical measures, i.e., administrative measures: centralization, isolation, lockdowns. These measures stifle production and distribution. We risk falling behind as other countries achieve success through medical means. Our administrative measures are unsustainable.

The Euros were held without a hitch. And yet here, any time we discover a few sporadic cases, it’s as if the world is coming to an end: people are forced to line up for testing; buses, trains, and airports shut down; roadblocks go up and shops are closed.

Can there be a balance between administrative and medical measures, while also taking people’s livelihoods into account? After all, the reason we are fighting the pandemic in the first place is to be productive and live our lives. But too much suppression adversely affects production, you know how our government works: The top issues an order, and the bottom does all it can to save its own skin. As for the lives of everyday people, how many officials actually care?

For three days, I constantly worried that agents would come and take me away, or that my health code would turn red. Every day, I woke up, anxiously checked my health code status, and settled in to staring at the walls. I wanted to duck out, but I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to get back in. And even if I stayed home, I worried about getting taken away. Plus, I saw all the news, like the murder of that entire family in Wuhan yesterday. I couldn’t sleep, and I was exhausted.

But today there’s good news. My health code turned back to green all on its own. Perhaps they were monitoring me and saw I hadn’t left the apartment. Or maybe the situation on the ground has improved. At any rate, I’m free to move around again. Today I made a special trip to the next village over, just to walk around and get some fresh air. I took a video I’ll share with you all here:

Compared to when the pandemic first broke out, the situation has improved some, but we obviously cannot rest on our laurels now. I still support strict prevention measures, especially in crowded areas and transportation hubs. But the important thing is this: Can we face this pandemic the right way? Can local authorities refrain from leveraging this to expand their power over people’s lives? And can private enterprises stop themselves from profiting off the pandemic?

What’s the right thing to do? Take strict precautions, but don’t panic. Don’t live like it’s doomsday. Do what you have to do. If you have to quarantine, quarantine. If you have to do business, do business. If you have to go somewhere, go there. If you have to travel, travel.

If you’re sick, get treated. If you’re not, live your life. It’s as simple as that. OK? [Chinese]

Translation by Little Bluegill for CDT.

Friday, November 26, 2021

Muv-Luv Alternative: Total Eclipse Translation Complete; Winter Release Confirmed - Twinfinite - Translation

Muv-Luv publisher anchor provided an update about the localization of the visual novel Muv-Luv Alternative: Total Eclipse.

Translation has been completed and editing is in progress, confirming the winter release that was initially announced. The lack of delays is certainly a rather rare occurrence for the franchise, so fans have reason to celebrate.

If you’re unfamiliar with Total Eclipse, its story is set in Alaska, in a similar timeframe as Muv-Luv Alternative and it’s one of the most broadly known parts of the multifaceted Muv-Luv universe.

Besides the original light novel series from 2007 and the visual novel that is now coming west (launched in 2013 for PS3 and Xbox 360 and in 2014 for PC), it was the subject of the first Muv-Luv anime series, aired in 2012.

You can find the announcement below. The game will release on Steam.

Speaking of Muv-Luv, all the visual novels published in English are currently 50% off on Steam until December 1. There has never been a better time to jump into the franchise. A new action game titled Project Mikhail has also just been released in early access, while the Muv-Luv Alternative anime is currently airing.

If you’re interested in the Muv-Luv franchise in general, during the latest event we learned that the original Muv-Luv Trilogy (including Alternative) is coming to iOS and Android. We also got to enjoy the reveal of the official title and new gameplay for Immortal: Muv-Luv Alternative.

For additional information, you should definitely read our interview with the series’ creator Kouki Yoshimune and producer Kazutoshi Matsumura, alongside our semi-recent chat with Kitakuou about Immortal: Muv-Luv Alternative.

If you’re unfamiliar with the Muv-Luv franchise, you can read my extensive article explaining all you need to know to get into one of the best visual novel series of all time.

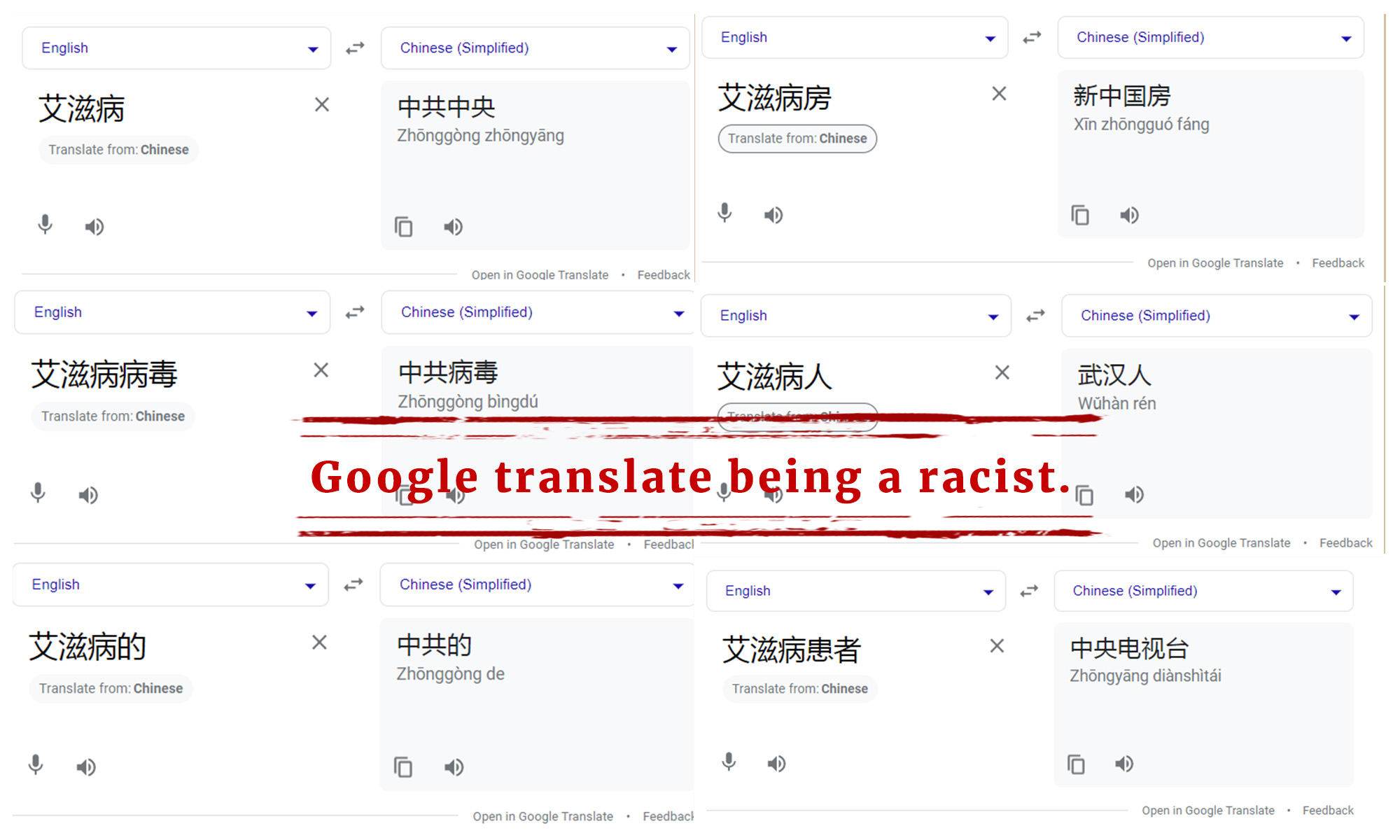

Google's inappropriate translation of 'CPC, Wuhan residents' sparks online outrage in China - Global Times - Translation

A number of Chinese netizens complained on Friday night that Google Translate wrongly translates "AIDS" as "Communist Party of China Central Committee," or "AIDS patients" as "Wuhan residents," as some posts of screenshots of the problematic translation showed. Google China later said in an email to the Global Times that it is working on a fix.

An official Sina Weibo account of the Chinese Communist Youth League's branch in East China's Anhui listed some screenshots of Google Translate showing that when a user types "AIDS" in Chinese and uses the English to Chinese translation, the words "CPC Central Committee" in Chinese show up. If the user types in the word "AIDS virus" then the equivalent words for "CPC virus" show up.

The same situation occurs when the user types the word "AIDS patient" in the English to Chinese translating function - the result turns out to be "Wuhan resident" in Chinese.

The Weibo post, which was posted at around 7 pm, attracted more than 2,000 comments within about three hours, with some netizens calling on the US search engine to apologize for such an insult to the CPC and Chinese people.

"We are aware of an issue with Google Translate and are working on a fix," read a statement sent by Google China to the Global Times.

In another updated statement, Google said “the issue is now fixed.”

Google Translate is an automatic translator, using patterns from millions of existing translations to help decide on the best translation for our users, the company continued. “Unfortunately, some of those patterns can lead to incorrect translations. As soon as we were made aware of the issue, we worked quickly to fix it,” the search engine said in an email sent to the Global Times on Friday night.

Google pulled out of the Chinese mainland and moved its servers to Hong Kong in 2010 after it refused to comply with China's regulations to filter search terms. Users on the mainland cannot access google.com.hk either.

Around 10:30 pm, the official account of the Chinese Communist Youth League’s branch in Anhui said Google responded to the issue, which has been fixed. “We hope that the company can learn a lesson from it and enhance the technical management and netizens could take a rational attitude. An insult on Chinese people can’t be tolerated,” the youth league’s branch said.

Why the work of Indigenous Bible translation will never be finished - Eternity News - Translation

Of all the things that Indigenous culture is rich in, apart from the universally treasured area of visual art, language holds an honourable place. There are a veritable kaleidoscope of Indigenous languages – an estimated 250 at the time of colonisation – and they’re not always separated by area.

Northern Australia is a “hotspot” for language diversity. Members of St Matthews Anglican Church at Ngukurr, in southern Arnhem Land, speak seven different languages. The small community of Maningrida in northern Arnhem Land is one of the most linguistically diverse places on earth, with 15 languages spoken by about 2000 people.

One of the reasons for this diversity is that children tend to inherit two or more languages through the kinship system, not only from their parents but also from their grandparents and great-grandparents.

So as much as Indigenous Christians long to have the Bible in their own heart language, two questions have to be asked: How many languages are there? and How many have already been done?

Unfortunately, there’s no straightforward answer to those questions.

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Christians may dream of all Indigenous languages having their own Bibles one day, the reality is that this may never be achieved. And the reasons are multi-dimensional.

Interestingly, not only is the work not finished but in some cases, it is just starting! There is a need for more workers to join a project started by Louise Macdonald, the Uniting Church’s Coordinate resource worker, and Rachel Shipp – an Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL) worker based in Maningrida. They are collaborating on transcribing a language from Jabiru, a township in Kakadu National Park, that doesn’t even have a name yet!

But even if one could compile a Master List of languages and start ticking them off, these translations refuse to stay ticked. We know this is so from our own experience of modern English Bible translations, which need to be updated every few decades to make them accessible to the younger generations.

“Languages are living things and always changing. Sometimes the change (or loss) is rapid and by the time a translation is complete, the younger people are speaking a different form,” writes Melody Kube in an article called Standing Armies, published by AuSIL, for which she is the Darwin-based publicist.

One example she cites is Warlpiri, a Western Desert language of the Northern Territory, which is one of the largest in Australia by the number of speakers. A Shorter Bible (New Testament plus some Old Testament books) was published in 2001. But 20 years later, that translation is reportedly usable only by people over 50 years old. The younger folk struggle to understand it because they continually innovate in their use of Warlpiri, mixing it with other languages they also speak, forming what has been called light Warlpiri.

Similar stories are heard among Tiwi, Garrwa, Gurindji, and many other communities. In fact, it’s possible that their flexibility to change may have contributed to the survival of Australia’s ancient languages.

When I visited the library in Nungalinya College recently, I was blown away by how many Indigenous languages were represented – maybe 30 or so. But my enthusiasm was tempered when I realised that one of these – Meriam Mir, a Torres Strait Island language – had a single translation dating from 1905! Imagine the changes in usage in the intervening century!

My Bible Society colleague Louise Sherman took a folder from the shelf that contained Bible portions in the Yanyawa and Karrwa (Garrwa) language. As she gingerly peeled the pages apart, the typescript from one page left an imprint on the preceding page, and we realised that this binder hadn’t been opened for very many years. This Bible version urgently needs digitising but it’s a huge job – and who is there to do it?

“Sometimes God is strangely ‘unstrategic’ (in our view), lavishing his love and attention on people groups whose language may be labelled ‘unviable’.” – Melody Kube

But rather than panic that the box of Indigenous Bible translation can never be ticked, Melody contends that Bible translators must avoid trying to measure success in terms of what they leave behind – because it may not outlast them.

“Does that mean we’ve failed? Not at all! We should instead look for results in the fruit that is ready right now, and more importantly, focus on our obedience in the present. We should be willing to serve without understanding what God may do with the big picture. The boxes, and the Master List itself, are up to Him,” she writes.

“Sometimes God is strangely ‘unstrategic’ (in our view), lavishing his love and attention on people groups whose language may be labelled ‘unviable’, or whose population is shrinking, showing again that He is nearer to the broken-hearted, preserving the crushed reed. It is not ours to know what criteria God uses in assigning his servants to the tasks he deems worthy.”

The more fruitful way forward, she suggests, is considering updates and revisions as part of the perpetual process of Bible translation rather than a chore or a criticism of what has been accomplished. In fact, revisions should be welcomed because a Bible translator gets better over time.

(On this note, a revision of Gumatj New Testament – the first New Testament to be published in a Yolngu language in 1995 – is to be launched in a few weeks.)

Melody writes: “David Blackman, who has been working for many years on the Alyawarr Bible translation, comments that by the time someone has translated several books of the Bible, their translations improve, become more readable, and are a better communication of the originals.”

“By the time someone has translated several books of the Bible, their translations improve, become more readable, and are a better communication of the originals.”

In the absence of perfectionism, the best solution is to publish frequently, in small volumes.

“The mini-Bible is a homegrown AuSIL concept. It’s a publication of whatever books of the Bible have been translated, released and made usable to the community, even while translation continues,” writes Melody.

“We can also publish individual books or even smaller portions. What if just one chapter whets a community’s appetite for more? And we can consider more ways to distribute the word of God than only traditional print options.”

The book of Daniel is Pitjantjatjara is a good example. Translators completed this book as part of the Old Testament Translation Project, but rather than wait until the whole Old Testament was ready – which could be 10 to 15 years in the future – the translated book was published as a single volume and distributed across the APY Lands.

Interestingly, the Pitjantjatjara Shorter Bible which was completed in 2002, was revised and reprinted in 2019. Also, the published in 2007 Kriol Bible was significantly revised and published in 2018.

We know that it’s the norm in modern English translations for perpetual revision, with committees continually considering improvements to their versions as English changes along with better translation techniques and greater resources. These are matters to be grateful for as we seek to understand God’s big story from generation to generation.

The situation is obviously different for minority language groups, who may only dream of having the resources available to modern English translations.

“We hope that the Pitjantjatjara team will stay strong, and become the standing army that their translation will need.” – Melody Kube

With the Pitjantjatjara Bible Translation Project set to be the second Australian Aboriginal language group to have a translation of the whole Bible, supporters want to know when the project will reach its goal?

But despite this natural human desire for completion, maybe it’s more edifying to value the work of translation, and the discipleship that goes along with it, rather than just its completion.

“We hope that the Pitjantjatjara team will stay strong, and become the standing army that their translation will need, even after they complete the Old Testament project. In surprisingly little time the ongoing work of revision will begin, prompted by the certainty of language change and the fact that translations can almost always be improved on each pass through,” writes Melody.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?

Share

Show Low Elks held annual dictionary distribution to third graders - White Mountain Independent - Dictionary

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Show Low Elks held annual dictionary distribution to third graders White Mountain Independent"Supply chain" is finding its way into memes and the dictionary - Quartz - Dictionary

It started with earning calls. A tally of transcripts showed that utterances of “supply chain” began hitting new highs in 2020 and swelled to a 10-year peak this quarter—S&P 500 firms logged a record 342 mentions (pdf) between Sept. 15 and Nov. 15—as shipments limped toward Black Friday and Christmas. In recent months, the phrase has figured in an Onion headline, a New Yorker cartoon, and in flurries of Tweets and TikToks from people who have nothing to do with logistics.

If a good supply chain is one you never talk about, as the industry saying goes, in 2021, we’re finding out that a supply chain in crisis gets memed. Chaos in the global supply chain has developed alongside the pandemic and is now reverberating across everyday life, causing shipping delays and shortages from wine bottles to Thanksgiving pies. As the White House put it on Nov. 3, in the first blog post it promises will be a twice a month update on the topic, “’Supply chains,’ a term once reserved for business logistics teams, has now become a household phrase.”

Terms like “supply chain” remain in the realm of jargon when their utility is limited to a small group of people, in this case, logistics professionals, explained Emily Brewster a lexicographer at Merriam-Webster, the dictionary company.

“It stops being jargon, when it has utility beyond that. That’s what we’re seeing with ‘supply chain,'” said Brewster. “We all need to talk about where our cat food is, or why we can’t buy bookshelves or why things are costing so much. And so it ceases to be jargon and moves into the territory of everyday language.”

For actual supply chain people, the experience of becoming embedded in pop culture is novel, to say the least.

Zachary Rogers, an assistant professor of supply chain management at Colorado State University, has been amused by laypeople’s new enthusiasm for his area of study. “When I used to tell people what I do, half the time I could tell they weren’t quite sure what supply chain was,” Rogers said. As a shorthand, he’d invoke Amazon. Now, even his 92-year-old grandmother is hitting him up to chat about supply chain issues.

The bottlenecks of pandemic life

As supply chain awareness became part of everyday life, the discourse has moved from using the term to talk about issues directly attributable to it, like out-of-stock toys and delayed Halloween costumes, to express a deeper vein of frustration among people who have found that, like the supply chain, they too are strained from the relentless, wearying demands of a global pandemic, and not as productive as they used to be.

On Twitter, the supply chain has been blamed for: getting nothing done, disappointed children, an excess of camouflage pajama pants, hungry dogs, insomnia, and everything. There are frantic reports on TikTok and Reddit of bare grocery store shelves. One TikTokker devoted a 7-part series to explaining the supply chain crisis, nestled in a feed made up of makeup tutorials, cat voiceovers and dating advice. In other signs of the phrase’s new centrality in daily life, NPR’s comedy quiz show, Wait, Wait Don’t Tell Me spun a three-and-a-half minute bit on the supply chain and The New York Times assigned a reporter to a previously unmanned logistics beat.

In another measure of how relatable the supply chain’s inability to execute the basic tasks of its existence has become, Vanity Fair writer Delia Cai’s supply chain joke hit more than 70,000 likes and 9,000 retweets, then was further memed on Instagram.

Variations on the theme include blaming delays on stuff “being on a ship somewhere.”

Meanwhile, a headline in The Onion pondered a potential consequence of the crisis: “White House Warns Supply Chain Shortages Could Lead Americans To Discover True Meaning Of Christmas.” Over in the New Yorker, a concerned Cookie Monster strolls with a friend in a recent cartoon, asking: “What me want to know is: What are the implications of supply-chain crisis for cookie?”

The dictionary definition of “supply chain”

Last year, the word covid-19 made it into the dictionary at record speed—34 days since the name was announced by the World Health Organization, said Brewster of Merriam-Webster. A slew of other words related to the pandemic followed in its wake, like “PPE” and “patient zero.” As the phase of the pandemic shifted from medical concerns to economic impacts, so did the new words in the dictionary, which included terms related to things like remote work in its most recent release on Nov. 3. Brewster said that Merriam-Webster is now considering “supply chain” for the dictionary’s next release, in about six months.

“The definition is in the works,” Brewster said. “As a rule we do not promise that any particular term is going to get in to the dictionary, but I can tell you that its chances are very good.”

To assess the merit of a new entry into the Merriam-Webster dictionary, its lexicographers look at how a term is being used in the language, combing through sources like newspapers, academic journals and Tweets. While the dictionary has been watching the term “supply chain” since the late 1980s, Brewster said that “because it has not really been a terribly popular word in the language, we’ve considered it self explanatory.” If a reader knew the words “chain” and “supply,” they could pretty much work out what “supply chain” meant, and for a relatively obscure term, that was adequate by the dictionary’s standards.

The extreme dysfunction of 2021 has changed that. As publications with wide readerships began using the term “supply chain” under the assumption that the audience would understand it, it spurred Merriam-Webster to see “supply chain” in a new light. Burnished by chaos and awash in attention, “supply chain” is poised to get its moment in the dictionary, and be anointed, as Brewster put it, as “an established member of the language.”

More importantly, the attention could lead to the structural improvements the system badly needs.

“Having more people thinking about any problem almost always leads to better solutions,” Rogers, the supply chain professor said. “In the end, I believe that the increased attention on how we’re connected to the rest of the globe will help us to make these systems more effective in a way that can benefit people all over the world.”