[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Pioneering German Translation of the Talmud from 1935 Now Accessible Online Jewish ExponentMonday, October 18, 2021

Springer Nature introduces free auto-translation service for books and manuscripts - The Bookseller - Translation

Springer Nature has introduced a free auto-translation service for books and manuscripts for its authors

Springer Nature has introduced a free auto-translation service for books and manuscripts for its authors.

The move seeks to reduce language barriers and follows a successful pilot using DeepL AI. The publisher said it would use the technology "to fill a critical gap and seamlessly integrate auto-translation into its book publishing process". The service will be available for book authors across all disciplines as well as for submitted manuscripts, enabling them to translate their work from multiple languages, including German, Chinese and French, into English.

A human check is carried out for accuracy of the translated content and translations are only published with the approval of authors who retain copyright over the original and the translation.

Stephanie Preuss, senior manager for product and content solutions, said: “Feedback from our authors is that translating their books and manuscripts is costly and often time-consuming. The Springer Nature translator uses technology to improve research, open up new possibilities for authors and help us advance discovery. It will hopefully enable authors, who may not have otherwise, to publish their work in more than one language.”

Springer Nature is holding an event on the role AI can play in changing science and open research as part of it virtual presence at this week's Frankfurt Book Fair. “How Artificial Intelligence and machine learning is opening up science” will take place on 21st October at 12 p.m. CEST. Recordings of the event will be made available afterwards.

Great New Nonfiction in Translation - Book Riot - Translation

When it comes to books in translation, fiction and poetry usually get the most attention. Major prizes, reading lists, and book chatter tend to focus on those two genres, especially fiction. As someone who follows books in translation closely, I do see fewer nonfiction books on offer.

But as a reader of both nonfiction and of books in translation, I’m always on the hunt for where these areas overlap. Give me more memoirs, essays, travel books, nature books, and all kinds of nonfiction from around the world, please! We need to hear from writers everywhere who work in all different kinds of forms and modes.

The books below include memoir, essay, nature, and science writing. They touch on topics as varied as #MeToo, climate change, and state violence. They also dive into personal issues such as memory, identity, the body, and becoming an adult. These books are varied, innovative, and exciting.

All the books below have come out in English in the last year, some of them in the last month. Translation takes time, however. Usually books come out in their home countries earlier than their translations, in some cases much earlier. But this list offers some of the most exciting nonfiction work newly available to English readers. Here’s hoping for more!

Take a look at the list and explore some fabulous nonfiction from around the world!

Migratory Birds by Mariana Oliver, Translated by Julia Sanches

This book is part of Transit Press’s fantastic “Undelivered Lectures” series, which features book-length essays from authors around the world. Mariana Oliver writes about many kinds of migration, from literal travel to metaphorical journeys through language, pain, and memory. She ranges from migrating birds to the history of Berlin to the underground city of Cappadocia. It’s an essay collection that blends personal writing with history and reporting to explore what it means to be in movement.

Distant Fathers by Marina Jarre, Translated by Ann Goldstein

This autobiography was originally published in 1987 and is newly translated into English. Marina Jarre tells the story of growing up in Latvia in the 1920s and ’30s and then her later move to the Italian countryside as an adolescent. She writes about her complicated family history, including her Jewish father who died in the holocaust and her Italian mother who translated Russian literature. The book explores her shifting identities and asks questions about the nature of home and belonging.

Black Box by Shiori Ito, Translated by Allison Markin Powell

This book is subtitled “The Memoir That Sparked Japan’s #MeToo Movement.” Originally published in 2017, it became the center of cultural and legal changes in how sexual assault and rape are treated in Japan. Journalist Shiori Ito tells her story of being raped by a famous reporter. She describes how her case was treated as a “black box,” as untouchable. It’s a wrenching personal story. It’s also a look at how the Japanese legal system and society at large have failed to support victims of sexual assault and rape.

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova, Translated by Sasha Dugdale

Some call In Memory of Memory a novel, so arguably it shouldn’t be on my list. But it’s a genre-bending, unclassifiable mix of essay, memoir, travel, and history, as well as fiction. After the death of her aunt, the book’s narrator sifts through her apartment with its letters, postcards, and souvenirs. With these pieces, the narrator tells the story of an ordinary family trying to survive the devastations of the 20th century. It’s a beautiful meditation on family, history, and memory.

A Girl’s Story by Annie Ernaux, Translated by Alison L. Strayer

A Girl’s Story is an account of 18-year-old Annie Ernaux in 1958 when she leaves home for the first time to work as a camp counselor. Ernaux examines not only what happened during this period and in the years after, but also how she feels about the experience from the vantage point of 50 years later. The book is a beautiful contemplation of desire, memory, time, and the self. It’s also the story of how Ernaux emerged from this difficult period as a young woman ready to become a writer.

I Live a Life Like Yours: A Memoir by Jan Grue, Translated by B.L. Cook

Subtitled “a memoir,” this book contains elements of essay as well. Jan Grue reflects on philosophy, film, art, and writing at the same time as he tells his story of living with spinal muscular atrophy. It’s a story of a child coming to understand his vulnerable body and an adult trying to negotiate life in a wheelchair. In the vein of Maggie Nelson and Anne Boyer, Jan Grue combines ideas and stories to explore living with one’s body’s limitations. It’s an important addition to the literature of disability.

Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country by Cristina Rivera Garza, Translated by Sarah Booker

This collection looks at the effects of violence and mourning in contemporary Mexico. Cristina Rivera Garza tells stories of those lost in violence and those who grieve them. She analyzes the relationship of the state and drug wars and reflects on what years of violence have done to the country and its culture. The book is a mix of personal, journalistic, poetic, and philosophical writing. It’s sobering and wise and beautiful.

On Time and Water by Andri Snaer Magnason, Translated by Lytton Smith

In On Time and Water, Icelandic author Andri Snaer Magnason grapples with climate change. He approaches the issue with both realism and hope. The book combines personal writing, travel, science, and history, and makes a plea for immediate action. It ranges from glaciers to his family history to the Dalai Lama, looking at climate change from a broad, varied perspective. Focusing on his personal connection to glaciers, Magnason offers a wise-ranging and philosophical approach to our most pressing crisis.

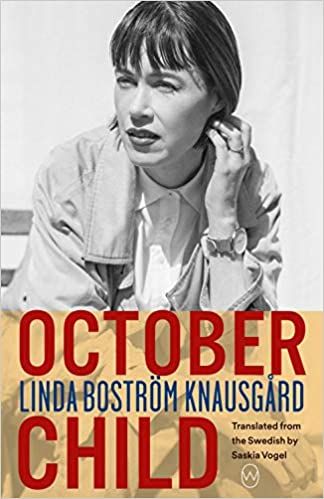

October Child by Linda Boström Knausgård, Translated by Saskia Vogel

October Child is a memoir about Linda Boström Knausgård’s struggle with mental illness and isolation. Between 2013 and 2017, Linda Boström Knausgård spent some time in a psychiatric ward and was treated with electroshock therapy. This resulted in the loss of some of her memory. The book explores with what it means to be a writer whose memories are disappearing. It tries to make sense of identity, stories, and writing in the face of loss and suffering.

On the lookout for more great books in translation? Check out our list of 2021 new releases by women in translation and 24 must-read 2021 books in translation. Want more excellent nonfiction? We have an introduction to literary nonfiction post and a list of 50 of the best nonfiction books for you.

Dictionary donation | News West Publishing - Mohave Valley News - Dictionary

Sunday, October 17, 2021

Squid Game: why you shouldn't be too hard on translators - The Conversation UK - Translation

Squid Game has recently become Netflix’s biggest debut ever, but the show has sparked controversy due to its English subtitles. This occurred after a Korean-speaking viewer took to Twitter and TikTok to criticise the subtitles for providing a “botched” translation, claiming: “If you don’t understand Korean you didn’t really watch the same show.”

Only this year, Squid Game, Lupin, and Money Heist – all non-English originals – have consistently been at the top of Netflix’s most-watched shows globally. This growing popularity of productions in languages other than English and streaming platforms investing more in them has led to an increase in the visibility of the work of translators.

When it comes to translating films and series, subtitling and dubbing are the most common forms of translation. Subtitles show the dialogue translated into text displayed at the bottom of the screen; while in dubbing, the original voices of the characters are replaced with voices in a new language.

Translation is not new to viewers, but the instant, almost frictionless access to different language versions of the same film or show definitely is. Streaming platforms allow viewers to swiftly change from watching a film with subtitles to listening to the dubbed version or the original. This creates an opportunity for viewers to compare the different versions.

Why do originals and translations differ?

Just because the translation doesn’t say exactly the same as the original, it doesn’t mean it’s wrong. Films and TV series are packed with cultural references, wordplay and jokes that require changes and adaptation to make sure what’s said and seen on screen makes sense across languages.

Making allowances and adapting what’s said are common practices in translation because, otherwise, the translators would need to include detailed notes to explain cultural differences.

Consider the representations of washoku (traditional Japanese cuisine) which are so beautifully embedded in Studio Ghibli films. While additional explanations about the significance of harmony, kinship and care represented in the bowls of ramen in Ponyo or the soft steaming red bean buns in Spirited Away could be interesting, they might get in the way of a viewer who just wants to enjoy the production.

Professional translators analyse the source content, understand the context, and consider the needs of the variety of viewers who will be watching. They then look for translation solutions that create an immersive experience for viewers who cannot fully access the original. Translators, similarly to screenwriters and filmmakers, need to make sure they provide good, engaging storytelling; sometimes that implies compromises.

For instance, some original dialogue from season two of Money Heist uses the expression “somanta de hostias”. Literally, “hostia” means host – as in the sacramental bread which is taken during communion at a church service. But it is also Spanish religious slang used as an expletive.

Original: Alberto, como baje del coche, te voy a dar una somanta de hostias que no te vas ni a mantener en pie.

Literal translation: Alberto, if I get out the car, I’m going to give you such a hell (hostia) of a beating that you won’t be able to stay on your feet.

Dubbed version: If I have to get out of the car, I’m gonna beat you so hard you don’t know what day it is.

Subtitles: Alberto, if I get out of the car, I’ll beat you senseless.

The dubbed version of the dialogue adopts the English expression “to beat someone”. The subtitled version uses the same expression but offers a shorter sentence. The difference between the two renderings reflects the constraints of each form of translation.

In dubbing, if the lip movements don’t match the sound, viewers often feel disconnected from the content. Equally, if subtitles are too wordy or poorly timed, viewers could become frustrated when reading them.

Read more: Squid Game: the real debt crisis shaking South Korea that inspired the hit TV show

Dubbing needs to match the duration of the original dialogue, follow the same delivery to fit the gesticulations of the characters, and adjust to the lip movements of the actors on the screen. Subtitles, on the other hand, need to be read quickly to keep up with the pace of the film. We talk faster than we can read, so subtitles rarely include all the spoken words. The longer the subtitle, the longer the viewer will take to read it and the less time they will have to watch. According to Netflix policies, for example, subtitles can’t have more than two lines and 42 characters, and shouldn’t stay on the screen for longer than seven seconds.

Additionally, in the above example, the translations do not reflect the reference to religious slang, typical of Spanish culture. Rather than fixating on this reference and assuming it is an essential part of the dialogue, a good translator would consider what an English-speaking character would say in this context and find a suitable alternative that will sound natural and make sense to the viewer.

New rules of engagement

It is encouraging to see that some viewers are so devoted to the content they watch: foreign films and TV shows help promote cultural understanding and empathy. But not all viewers act in the same way and the solutions provided by the translators need to cater to everyone who decides to watch the show.

This leads to different viewing experiences, but it only reflects the reality of watching any culturally charged product, even in our own languages. In English, for instance, consider all the references and nuances that a British viewer could miss when watching an English-language film produced in South Africa, Jamaica or Pakistan.

Translators do not blindly look for literal translations. On the contrary, in the translation profession, hints of literal translation often signal low-quality work. Translators focus on meaning and, in the case of films and series, will endeavour to provide viewers with a product that will create a similar experience to the original.

The case of Squid Game has been instrumental in bringing discussions about translation to the fore. Of course there are good and bad translations, but the main gain here is the opportunity to debate what determines this. Through such discussions, viewers are becoming more aware of the role and complexities of translation.