When it comes to books in translation, fiction and poetry usually get the most attention. Major prizes, reading lists, and book chatter tend to focus on those two genres, especially fiction. As someone who follows books in translation closely, I do see fewer nonfiction books on offer.

But as a reader of both nonfiction and of books in translation, I’m always on the hunt for where these areas overlap. Give me more memoirs, essays, travel books, nature books, and all kinds of nonfiction from around the world, please! We need to hear from writers everywhere who work in all different kinds of forms and modes.

The books below include memoir, essay, nature, and science writing. They touch on topics as varied as #MeToo, climate change, and state violence. They also dive into personal issues such as memory, identity, the body, and becoming an adult. These books are varied, innovative, and exciting.

All the books below have come out in English in the last year, some of them in the last month. Translation takes time, however. Usually books come out in their home countries earlier than their translations, in some cases much earlier. But this list offers some of the most exciting nonfiction work newly available to English readers. Here’s hoping for more!

Take a look at the list and explore some fabulous nonfiction from around the world!

Migratory Birds by Mariana Oliver, Translated by Julia Sanches

This book is part of Transit Press’s fantastic “Undelivered Lectures” series, which features book-length essays from authors around the world. Mariana Oliver writes about many kinds of migration, from literal travel to metaphorical journeys through language, pain, and memory. She ranges from migrating birds to the history of Berlin to the underground city of Cappadocia. It’s an essay collection that blends personal writing with history and reporting to explore what it means to be in movement.

Distant Fathers by Marina Jarre, Translated by Ann Goldstein

This autobiography was originally published in 1987 and is newly translated into English. Marina Jarre tells the story of growing up in Latvia in the 1920s and ’30s and then her later move to the Italian countryside as an adolescent. She writes about her complicated family history, including her Jewish father who died in the holocaust and her Italian mother who translated Russian literature. The book explores her shifting identities and asks questions about the nature of home and belonging.

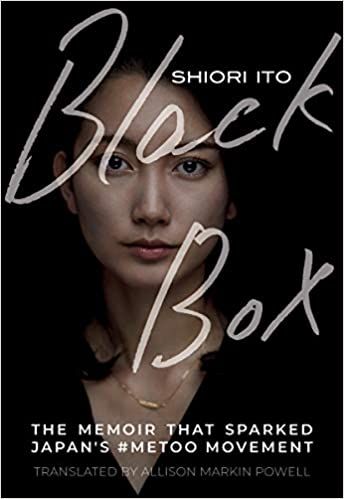

Black Box by Shiori Ito, Translated by Allison Markin Powell

This book is subtitled “The Memoir That Sparked Japan’s #MeToo Movement.” Originally published in 2017, it became the center of cultural and legal changes in how sexual assault and rape are treated in Japan. Journalist Shiori Ito tells her story of being raped by a famous reporter. She describes how her case was treated as a “black box,” as untouchable. It’s a wrenching personal story. It’s also a look at how the Japanese legal system and society at large have failed to support victims of sexual assault and rape.

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova, Translated by Sasha Dugdale

Some call In Memory of Memory a novel, so arguably it shouldn’t be on my list. But it’s a genre-bending, unclassifiable mix of essay, memoir, travel, and history, as well as fiction. After the death of her aunt, the book’s narrator sifts through her apartment with its letters, postcards, and souvenirs. With these pieces, the narrator tells the story of an ordinary family trying to survive the devastations of the 20th century. It’s a beautiful meditation on family, history, and memory.

A Girl’s Story by Annie Ernaux, Translated by Alison L. Strayer

A Girl’s Story is an account of 18-year-old Annie Ernaux in 1958 when she leaves home for the first time to work as a camp counselor. Ernaux examines not only what happened during this period and in the years after, but also how she feels about the experience from the vantage point of 50 years later. The book is a beautiful contemplation of desire, memory, time, and the self. It’s also the story of how Ernaux emerged from this difficult period as a young woman ready to become a writer.

I Live a Life Like Yours: A Memoir by Jan Grue, Translated by B.L. Cook

Subtitled “a memoir,” this book contains elements of essay as well. Jan Grue reflects on philosophy, film, art, and writing at the same time as he tells his story of living with spinal muscular atrophy. It’s a story of a child coming to understand his vulnerable body and an adult trying to negotiate life in a wheelchair. In the vein of Maggie Nelson and Anne Boyer, Jan Grue combines ideas and stories to explore living with one’s body’s limitations. It’s an important addition to the literature of disability.

Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country by Cristina Rivera Garza, Translated by Sarah Booker

This collection looks at the effects of violence and mourning in contemporary Mexico. Cristina Rivera Garza tells stories of those lost in violence and those who grieve them. She analyzes the relationship of the state and drug wars and reflects on what years of violence have done to the country and its culture. The book is a mix of personal, journalistic, poetic, and philosophical writing. It’s sobering and wise and beautiful.

On Time and Water by Andri Snaer Magnason, Translated by Lytton Smith

In On Time and Water, Icelandic author Andri Snaer Magnason grapples with climate change. He approaches the issue with both realism and hope. The book combines personal writing, travel, science, and history, and makes a plea for immediate action. It ranges from glaciers to his family history to the Dalai Lama, looking at climate change from a broad, varied perspective. Focusing on his personal connection to glaciers, Magnason offers a wise-ranging and philosophical approach to our most pressing crisis.

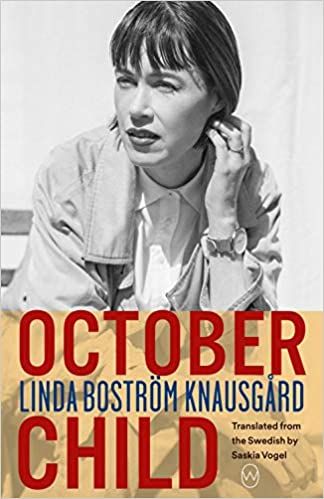

October Child by Linda Boström Knausgård, Translated by Saskia Vogel

October Child is a memoir about Linda Boström Knausgård’s struggle with mental illness and isolation. Between 2013 and 2017, Linda Boström Knausgård spent some time in a psychiatric ward and was treated with electroshock therapy. This resulted in the loss of some of her memory. The book explores with what it means to be a writer whose memories are disappearing. It tries to make sense of identity, stories, and writing in the face of loss and suffering.

On the lookout for more great books in translation? Check out our list of 2021 new releases by women in translation and 24 must-read 2021 books in translation. Want more excellent nonfiction? We have an introduction to literary nonfiction post and a list of 50 of the best nonfiction books for you.