The adage goes, "Two is better than one." Well, that might be true for endeavors involving human heads, but when it comes to ears, hybrid maize tends to have a superior advantage over the parental stocks in most cases. This phenomenon, called hybrid vigor or "heterosis," has been used by agriculturalists across ages to create higher-yielding, more resistant varieties of maize all over the world.

But what are the factors contributing to the increased hybrid vigor of maize? Several different genetic models have been proposed to explain heterosis in varied crops including maize, but none have hitherto been able to comprehensively unravel the mystery of heterosis.

A possible reason for this may be the complex genetic origin of the present-day maize species—Zea mays. Maize is supposed to have diverged from sorghum during an ancient speciation event, following which there was a duplication of the entire chromosomal materials or the genomic set in the ancestral stock via a process called polyploidization, giving rise to an ancestral tetraploid, or a plant with four genomic sets, i.e., double the usual number. Each genomic set in this tetraploid maize ancestor, called a subgenome, underwent dramatic breaks and fusion to eventually give rise to the current diploid genome (which bears two sets of genetic materials). During this genomic reorganization, redundant copies of genes from both subgenomes were lost through a process called fractionation.

In plants where such fractionation has been identified, including maize, there is a tendency for one subgenome to experience more gene loss than the other—a process called fractionation bias. For instance, the two subgenomes in present-day maize, termed maize1 and maize2, show differential expression of constituent genes, with maize1 typically identified as the dominant between the two.

It could be that differential expression of proteins coded by the maize subgenomes is responsible for the increased vigor of the hybrid maize lines, which are referred to as F1. However, this has not been clearly established. Until now.

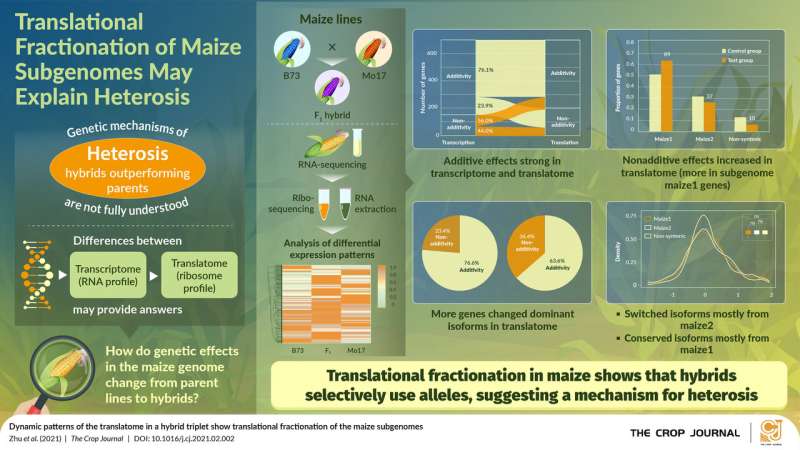

Now, researchers in China have explored the transcriptome (the full complement of protein-coding mRNA molecules derived from information coded in DNA) and translatome (the actual mRNA set that gets translated to proteins in cell) of maize to identify factors that may be potentially responsible for heterosis in maize.

Using the new ribosome profiling technique, the researchers, led by Professor Lin Li of National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, Huazhong Agricultural University, evaluated the maize parental lines B73 and Mo17, and their F1 offspring. Their findings, published in The Crop Journal, suggest the presence of prominent subgenome bias at the translation level, especially skewed towards translated subgenome maize genes, which had a nonadditive effect on heterosis in F1 plants.

Furthermore, some genes switched to the dominant form in the hybrid than in the parental lines, quite surprisingly. As Prof. Li observes, "More genes switched the dominant isoforms between the F1 and the two parents than between the two parents. This observation indicates that the best gene variant is more likely to be selectively utilized in hybrids for a given environment, leading to higher efficiency of protein accumulation in the hybrids."

Moreover, the switched gene isoforms mostly belonged to subgenome maize, while the conserved gene isoforms belonged to subgenome maize1. This knowledge, the researchers suggest, can help in selective breeding for further improving hybrid vigor.

Additionally, the researchers found evidence for additive effects of gene expression at both the transcriptome and the translatome levels in the hybrid. According to Prof. Li, "All these results are in accordance with the 'Goldilocks hypothesis,' suggesting that additive expression is advantageous for both transcriptome and translatome."

These findings suggest the potential role of asymmetric subgenome translation as an important factor contributing to heterosis in maize. These insights can provide crop breeders with effective gene manipulation tools to increase yield of not just maize, but other food crops, which might serve to address the looming food scarcity in face of the growing human population across the world.

Explore further

Provided by The Crop Journal

Citation: Gained in translation: Subgenome fractionation determines hybrid vigor in maize (2021, April 6) retrieved 7 April 2021 from https://ift.tt/3dxRRys

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

_1617690514359.jpeg)