'Devi's poems seem simple — just like something that would be said between friends — but they turn and twist within, move strangely, maybe even 'darkly.''

Kazim Ali is a prolific author whose body of work encompasses multiple genres – poetry, fiction, prose and translation. His latest book to be published in India — When the Night Agrees to Speak to Me (Harper Perennial, 2021) — is an English translation of Ananda Devi’s Quand la nuit consent à me parler. It was originally written in French as a collection of poems with three short prose pieces at the end.

Devi, who was born in Mauritius, and traces her roots to India, is considered to be one of the most important Francophone writers in the world. She is fluent in French, Mauritian Creole and English, understands Hindi and German, and has lost Telugu – the language that her mother spoke to her in. Ali was born in the United Kingdom, and has lived transnationally in the United States, Canada, India, France and the Middle East.

Ali picked up a copy of Devi’s book in a Parisian bookstore en route to India, and began reading it in Pondicherry – which was once under French colonial rule. The book seized his attention in a way that made him start translating the work to arrive at a deeper reading. In this exclusive interview over email, Ali – who is currently a Professor of Literature at University of California, San Diego – speaks at length about the craft of translation.

How would you describe the poetry of Ananda Devi to someone who has never encountered it before, either in French or in translation?

These poems seem simple — just like something that would be said between friends — but they turn and twist within, move strangely, maybe even "darkly." For sure, anger and resentment flare in these poems, emotions we do not normally express.

What kind of impact do her words have on you?

In French, though there is great pain in these short lyrics, there is a fluidity in language too, a "beauty" in the way the phrases flow and turn; translating them into English necessarily brought out a thornier affect — it had to: the sonic qualities of the language are different, the grammatical structure of English blockier and less "connective" and supple than many-joined French. It's a less subtle language in fact, deep in its syntactical bones.

Why did you commit to translating her poems into English?

It happened without me thinking. I was reading in French, but my French is self-taught; I was never formally educated. So, there were many places I didn't know a word, or occasionally a grammatical construction. But rather than pick up a dictionary at every point I just continued reading to glean what I could. At some point, I understood a poem as a poem itself even if there were words in it that I didn't know. I think it is when I started looking at the prose pieces that close the collection that I really thought I wanted to render the poems in English as a way of reading them more deeply. I did not expect the transformative quality they had on me.

Would you mind sharing how you learnt French, and the place it has in your life now?

I learnt it informally. One of my uncles was a French major (at the English and Foreign Languages University in Hyderabad) and moved to Paris after his graduation to work for a French company. He met his wife there and has lived there ever since. One of my cousins is a poet and English teacher, and we have stayed in touch throughout his life. I went to see him in Paris, and though he spoke English, I always wanted to speak to him in his own native language. I learnt by spending time with my family and with my cousin and his friends, and by reading French writers I loved, especially Marguerite Duras. French (like other colonial languages) is no longer a European language. It is a South Asian language, a Vietnamese language, and African language, a Caribbean language. The literatures of all these places belong both the Francophone world but also to a global literary tradition.

In what way did the sights and sounds of Pondicherry and Varkala enter your translations?

Well, I wasn't in Pondicherry long, just an afternoon, but it's there that I started the work. It was really Varkala — on a cliff overlooking the Arabian Sea — that I started to imagine the landscape of Mauritius. Ironically (I suppose) the landscape itself doesn't appear much in the poems; they're smaller, take place in intimate and domestic spaces for the most part. But it was somehow the vibe of the place, the aura, the atmosphere, whatever you want to call it. I had to enter into a perceptual sense, and it was there that that happened for me.

Which aspects of Ananda Devi’s work seemed most difficult to translate?

I think in general the feel of the French language is really impossible to duplicate in English sonically. There may be languages that have some prosodic concordance with one another, some closer in general rhythm: for example, English and Dutch might be a little closer or even English and Danish than English and German. As far as French goes, sonically and rhythmically, it might be closer to Italian or Portuguese than it would be (for example) to Spanish, which has certain sonic affinities to Greek.

How did her complex relationship with various languages mirror your own multilinguality?

That made it easier actually. Devi writes in French by choice. She could as easily write in English or Creole, but the decision to write in French is both an aesthetic decision but a cultural one as well. I spoke many languages as a preliterate young child but lived and learned to read and write in only one. I think my brain was changed by my early polyphonic language acquisition and even though I mostly still live in English, it still feels like a foreign country, one I've only lately arrived in.

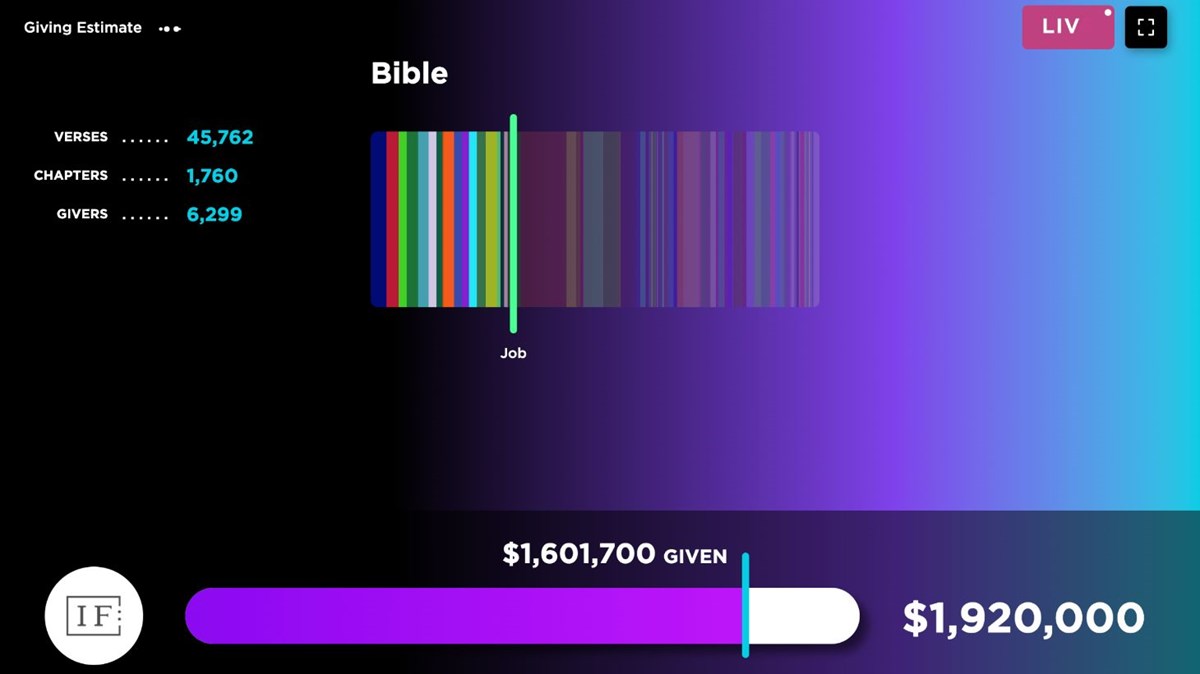

Cover image for When the Night Agrees to Speak to Me

In your Translator’s Note in the book, you say, “It was less karaoke and more full-blown drag.” Could you please help us unpack that statement? It seems that you are speaking as a translator, and as a queer poet fluent in the meanings and histories of drag.

It wasn't enough to just transmit the words, create a new version of those poems. I actually had to become Devi in a sense, I had to rewrite those poems as English poems. I was the poet who wrote those poems. I know they're not mine, I know that they're still hers, but there was something more — past "performance," closer to actual transformation that needed to take place within the body of the poem himself (myself) in order to write the English versions. And I wasn't just translating across languages, I was also translating across gender, and translating across age — they are the poems of an older woman, writing after a whole lifetime of experiences, which at the time (I did most of the initial work in 2012, though I finished somewhat after) I had not yet had.

How did your translations benefit from the comments you received from Ananda Devi?

She did read the translations and offered some feedback in the draft stage, but her comments were mostly in the area of clarifications. There were some very locally specific expressions I hadn't caught and at least one place where I had leaned into a colloquial meaning that she had not intended. But mostly — as she says in the interview we did that's included in the book — her interest is in writing her work; she does not translate it anymore (she did one of her own books in the past). She says it feels too much like rewriting a book, so she left me on my own. There was a panel we did later, at Oberlin College, where I was teaching, in which she expressed approval of the translations I'd done, even in a particular poem where I'd diverged not from her meaning but from the sound and rhythm, which one cannot properly duplicate in English. That meant a lot to me.

What points of convergence and conflict did you find between your own politics and hers?

I know friends who have translated work by poets with dramatically different political outlooks than they have, for example a friend in Israel who has translated the poetry of a very Zionist poet, a poet whose politics on the West Bank settlements are very different from her own, whose own literary community questioned why she was giving a platform to a poet she disagreed with politically. But thankfully, Ananda and I did not have such a divergence in political viewpoints.

To what extent did Ananda Devi's biographical details inform your appreciation of her poetry?

I didn't know much about them when I began, though I later came to understand more, particularly through her memoir Les hommes qui me parlent (The Men Who Talk to Me). Certainly, the more I learned about Mauritius and about Ananda's work, the better I was able to understand some of the themes and ideas in the poem. Some of the themes, like domestic violence, and the problem of child soldiers, she explores in different ways in novels like Le sari vert and La vie de Joséphin le fou (both as yet untranslated) and Le jours vivant (translated as The Living Days).

When you look back at your translations of Marguerite Duras, Sohrab Sepehri and Ananda Devi, what do you notice about your process as a translator?

In each case, it was falling in love with the work itself on its own terms, as literature in the other language. In both Duras' and Sepehri's case I read the work first in translation. The main — though not only — Duras translations I read were by Barbara Bray and Bray kind of created a Duras in English influenced (in my opinion) by Beckett's prose. It's a certain kind of Duras, not precisely the same as her French, but nonetheless a very distinctive voice in prose.

Sepehri I had only read a fairly weak translation of — his entire outlook as a poet is so embedded in Farsi literary traditions that it was nearly convoluted in English. I loved the images and the outlook, but it was beautiful as poetry in English, and so I viewed it as a kind of challenge. I don't read Farsi in fact, and so I teamed up with an Iranian scholar Jafar Mahallati and we did the work together, huddled over tables in coffee shops. He has the command of language that a poet would have, so it was very much a collaboration and I learned as much from him as I did from Sepehri. The work did not shed its complexity and there were times we'd spend a whole hour-long session on what a poem meant before we could even get to rendering it properly.

Whose work are you translating now/next?

I'm on a little pause from translation, though I have some coming out of Ivoirian poets; I did them a while ago though. I've also started studying Urdu during the pandemic and associated lockdown, so I've been working on Faiz Ahmed Faiz with my tutor. And some years ago, I did a few poems by Ahmed Faraz.

What has helped you hone your craft as a translator, and what advice would you offer translators who are starting out on their journeys?

I'd say study not only the language but also the culture, history, and literary traditions that produced the text you are trying to translate. If other translations exist of the author you are translating, I would suggest to read them, but read them and then put them aside; don't study them or engage too deeply. Translating is fun and it is also a great way of learning both language and about the text itself. I learnt more about Sepehri and Duras and Devi as well by translating them than I ever could have merely reading them. Perhaps what I mean is that translation is the deepest kind of reading.

How do you feel when you run into something that seems untranslatable?

Sometimes rather than "translate" it you have to rewrite it in the new language. It's a different poem in English, a new poem, but it draws from the same source, the same unspeakable experience that the "original" poem drew from. Walter Benjamin talks about this (in his essay The Task of the Translator) and I believe it: all poems, whether "original" or "translation" are attempts to translate the untranslatable, which is life itself, experience itself.

Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, educator and researcher who tweets @chintan_connect