[unable to retrieve full-text content]

The journey a number of econ terms recently went through to get into the dictionary WUNCFriday, September 30, 2022

Ministry updates official dictionary of careers - Chinadaily.com.cn - China Daily - Dictionary

China launched an updated State-level professions dictionary on Wednesday that includes 158 new professions such as cryptography engineer and financial technician, according to a dictionary of occupational titles issued by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

The updated dictionary is a result of the refined social division of labor and the emergence of new professions thanks to economic development and industrial upgrading, the ministry said. The dictionary is a revised version of those launched in 1999 and 2015.

"The profession dictionary plays a fundamental and instructive role in helping us plan out the market's needs for a labor force and in analyzing the working population. Also, it is beneficial to vocational education and employment guidance," ministry spokesman Lu Aihong said at an online news conference on Wednesday.

China's first State-level profession dictionary established a classification system adapted to the national situation at the time. The dictionary was revised in 2015 after the advancement of technology and the economic transformation of some professions.

Wu Liduo, director of the China Employment Training Technical Guidance Center, who is also director of the expert committee for the revision of the profession dictionary, said at the news conference that it classifies professions in eight categories adding 158 new professions.

"The dictionary now includes 1,639 professions covering manufacturing, digital technology, green economy and rural vitalization," he said. "We also adjusted the descriptions of over 700 professions."

He stressed that the dictionary highlighted 97 professions that are the offspring of the digital economy — roughly 6 percent of total professions.

"The digital economy is growing fast, with its market scale reaching 45.5 trillion yuan ($6.29 trillion) in 2021 — accounting for 39.8 percent of GDP," he said.

He added that including these digital economy-related professions in the dictionary can help speed up innovation of the digital economy and serve as a wind vane for working people.

"It will also be helpful to regulate the digital economy and give guidance to colleges when they plan courses and disciplines on the digital economy."

The ministry said it will organize central departments to draft or revise standards for these professions and develop teaching materials to allow companies and government bodies to carry out work on skills training and talent evaluation.

"We will establish our own system of professional information checkups to give people quick and convenient access to search information on different professions and market demands, as well as pay," said Liu Kang, the ministry's director of occupational capacity.

Thursday, September 29, 2022

Ministry updates official dictionary of careers - Chinadaily.com.cn - China Daily - Dictionary

China launched an updated State-level professions dictionary on Wednesday that includes 158 new professions such as cryptography engineer and financial technician, according to a dictionary of occupational titles issued by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

The updated dictionary is a result of the refined social division of labor and the emergence of new professions thanks to economic development and industrial upgrading, the ministry said. The dictionary is a revised version of those launched in 1999 and 2015.

"The profession dictionary plays a fundamental and instructive role in helping us plan out the market's needs for a labor force and in analyzing the working population. Also, it is beneficial to vocational education and employment guidance," ministry spokesman Lu Aihong said at an online news conference on Wednesday.

China's first State-level profession dictionary established a classification system adapted to the national situation at the time. The dictionary was revised in 2015 after the advancement of technology and the economic transformation of some professions.

Wu Liduo, director of the China Employment Training Technical Guidance Center, who is also director of the expert committee for the revision of the profession dictionary, said at the news conference that it classifies professions in eight categories adding 158 new professions.

"The dictionary now includes 1,639 professions covering manufacturing, digital technology, green economy and rural vitalization," he said. "We also adjusted the descriptions of over 700 professions."

He stressed that the dictionary highlighted 97 professions that are the offspring of the digital economy — roughly 6 percent of total professions.

"The digital economy is growing fast, with its market scale reaching 45.5 trillion yuan ($6.29 trillion) in 2021 — accounting for 39.8 percent of GDP," he said.

He added that including these digital economy-related professions in the dictionary can help speed up innovation of the digital economy and serve as a wind vane for working people.

"It will also be helpful to regulate the digital economy and give guidance to colleges when they plan courses and disciplines on the digital economy."

The ministry said it will organize central departments to draft or revise standards for these professions and develop teaching materials to allow companies and government bodies to carry out work on skills training and talent evaluation.

"We will establish our own system of professional information checkups to give people quick and convenient access to search information on different professions and market demands, as well as pay," said Liu Kang, the ministry's director of occupational capacity.

These 5 Python Dictionary Tricks Will Make you a Cool Senior! - Analytics Insight - Dictionary

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

These 5 Python Dictionary Tricks Will Make you a Cool Senior! Analytics InsightGoogle Search will soon begin translating local press coverage - TechCrunch - Translation

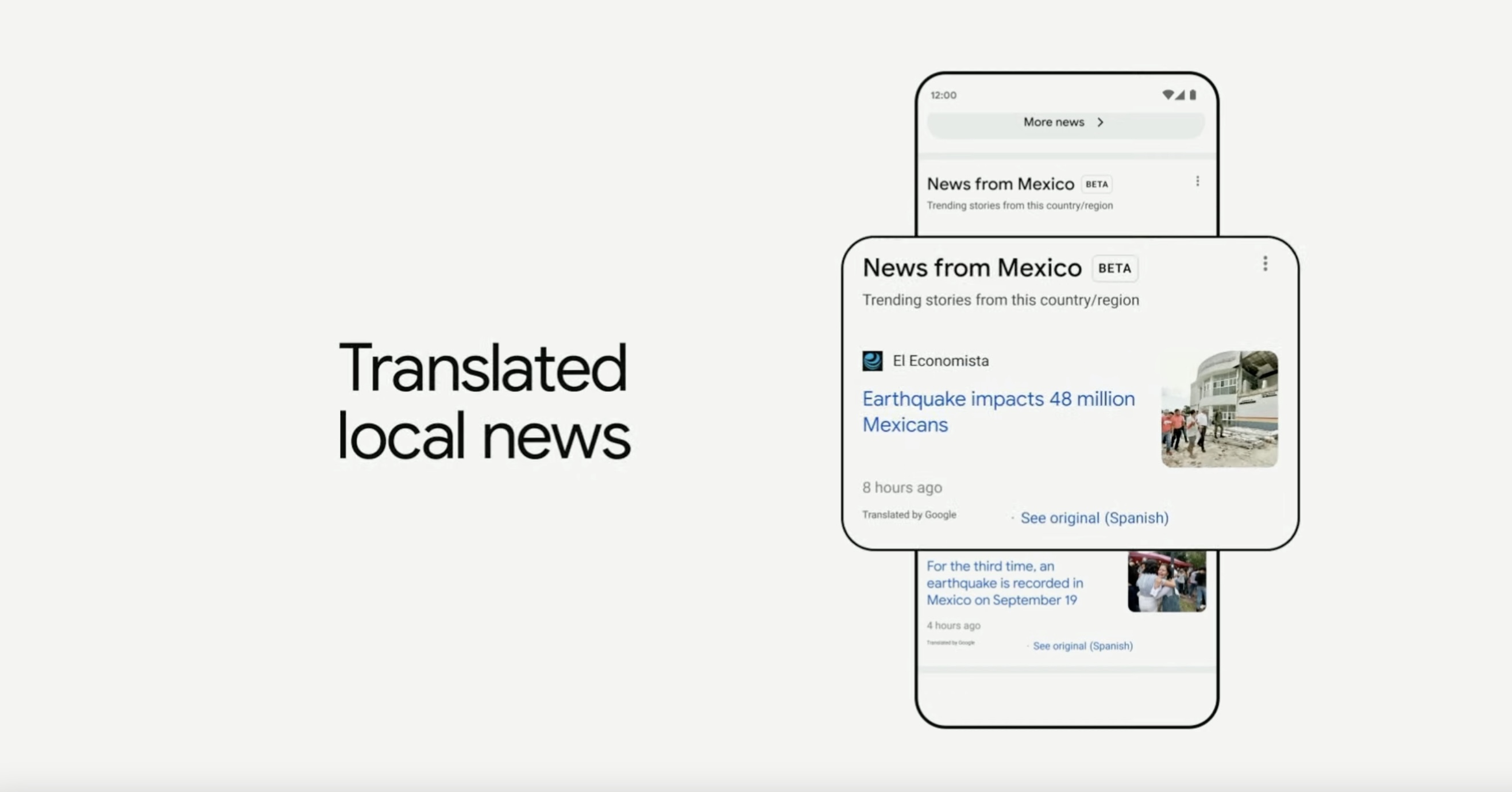

At a Google Search-focused event this morning, Google announced that it will soon introduce ways to translate news coverage directly from Search. Starting in 2023, English users, for example, will be able to search and see translated links to news results from Spanish-language publishers in countries such as Mexico, in addition to links to articles written in their preferred language.

“Say you wanted to learn about how people in Mexico were impacted by the more than 7 magnitude earthquake earlier this month,” Google News product manager Itamar Snir and Google Search product manager Lauren Clark explained in a blog post. “With this feature, you’ll be able to search and see translated headlines for news results from publishers in Mexico, in addition to ones written in your preferred language. You’ll be able to read authoritative reporting from journalists in the country, giving you a unique perspective of what’s happening there.”

Image Credits: Google

Building off its earlier translation work, the feature will translate headlines and articles in French, German and Spanish into English to start on mobile and desktop.

Google has experimented with news translation before, three years ago adding the ability to display content in two languages together within the Google News app feed. But for the most part, the search giant has left it to users to translate content via tools like Chrome’s translate button and Google Translate. Presumably, should the Google Search news translation feature be well received, that’ll change for more languages in the future.

Wednesday, September 28, 2022

Katara completes seven volumes of dictionary of everyday words - The Peninsula - Dictionary

Doha: The Cultural Village Foundation, Katara has completed seven volumes of the dictionary of daily life vocabulary and the first volume of the dictionary of places, as part of the bilingual “Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia” project.

The project includes several dictionaries, namely: Vocabulary of daily life, lexicon of places, lexicon of popular expressions, and a lexicon of popular proverbs.

Katara General Manager Prof Dr. Khalid bin Ibrahim Al Sulaiti said Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia project is of special importance as it works to introduce Qatar and its tourist, cultural and heritage attractions, noting that seven volumes of the daily life vocabulary will be printed in January 2023.

It is expected that this lexicon will contain about 20 volumes, and the number of volumes of the Al Makan Dictionary is expected to be three or four.

Khaled Abdel Rahim Al Sayed, supervisor of the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia project, said work is now underway to complete the first volume of the Dictionary of Places, which is an essential pillar in the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia to link places in Qatar with its authentic Arab history by rooting place names from linguistic dictionaries and others.

He linked it to poetic evidence, and documented information about each place through phonetic, morphological, semantic, lexical and encyclopedic analysis.

Al Sayed said the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia’s team consists of professors specialised in language, linguistics and literature at Qatar University, within the framework of scientific cooperation between the Katara Cultural Village Foundation and Qatar University.

Dr. Maryam Al Nuaimi, Director of the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia Project Execution Committee, said the seven parts that were prepared from the daily life vocabulary include Arabic alphabets from 'Hamza' to 'Kha', and they are working to complete the rest of the letters.

The first volume of the dictionary has been allocated for this.

As for the dictionary of places, it consists of 7,506 entries that include all the words that make up the names of places in Qatar. Abu, Abba, Mother and includes 13 nicknames, she explained.

She said the Dictionary of Places works on surveying the environment of places in Qatar, specifying the linguistic dimension and the dialect’s relationship to Standard Arabic, after which, the encyclopedic geographical dimension, so the user of the encyclopedia can search for one place consisting of more than one word, such as “Umm Salal Muhammad,” wherein he can search for Umm Salal or Mohammed, in addition to the root search.

Tuesday, September 27, 2022

International Translation Day 2022 - CSL Behring - Translation

CSL often translates one language into another and for good reason: The global biotech company has locations around the world and its 30,000 employees develop and manufacture medicines and vaccines for people in more than 100 countries.

A grand tour of CSL locations could start at a manufacturing site in Kankakee, Illinois; then skip across the Atlantic to major facilities in Switzerland and Germany; bound down to Australia, where CSL got its start; continue on to both Tokyo, Japan and Wuhan, China; and then return to the United States via CSL’s Pasadena office. CSL businesses, including CSL Behring, CSL Seqirus and CSL Vifor, together have 46 websites in languages other than English.

Day-by-day, translations happen so that CSL can continue to be driven by our promise.

Though in France, we say: Tout a commencé par une promesse.

And in Mexico: Impulsados por nuestra promesa

Antje Becker, who works in Communications at CSL’s Marburg, Germany location, has 30 years of translation experience, specializing in health, science and corporate environments. In honor of United Nations International Translation Day (30 September), we asked her about the art and a science of translation and why translators today sometimes use the term “transcreation.” In other words, Google Translate will get you only so far. Here’s how Becker explained it:

What makes a good translation? For me, there is one single principle that guides everything else:

The target text is to spark the same meaning and emotions in the target audience as the source text in the source audience.

The translation process is often reduced to the level of words, but it also applies to the levels of sentence, paragraph, general order of the entire text, the register and in a few cases even the text type itself. Essentially, the target text needs to be a rewritten version of the source text in a form that is linguistically and culturally appropriate for the target audience on all levels.

Done to the extreme, this is what the term “transcreation” denotes: The meaning of the source text is recreated using the means of the target language. It’s not a one-to-one translation but achieves its goal of saying the same thing to each audience.

So, a good translation does not give the impression of being a translation. It is as if it were conceived and written in the target language and for the target audience. To achieve this, the translator needs to be able to first assess the effect that the source text has on the source audience and then be able to create a target text with the same effect on the target audience. This is something literal translation and machine translation cannot provide and why they require professional and sometimes heavy post-editing.

In this, some content is more demanding than others. The more technical a text is, the more important pure facts are and the less pronounced the cultural influence is. Very technical machine-translated texts might require comparatively little post-editing, but even these cannot do without: a machine will inevitably make wrong choices when presented with several possible translations of one word in a dictionary. Machines cannot truly assess context on all levels, and – for a translator – context is king.

Read more about CSL employees working across different languages:

Sprechen Sie Deutsch? Bridging Language Gaps

To Buy, Purchase or Procure?

Katara completes seven volumes of dictionary of everyday words - The Peninsula - Dictionary

Doha: The Cultural Village Foundation, Katara has completed seven volumes of the dictionary of daily life vocabulary and the first volume of the dictionary of places, as part of the bilingual “Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia” project.

The project includes several dictionaries, namely: Vocabulary of daily life, lexicon of places, lexicon of popular expressions, and a lexicon of popular proverbs.

Katara General Manager Prof Dr. Khalid bin Ibrahim Al Sulaiti said Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia project is of special importance as it works to introduce Qatar and its tourist, cultural and heritage attractions, noting that seven volumes of the daily life vocabulary will be printed in January 2023.

It is expected that this lexicon will contain about 20 volumes, and the number of volumes of the Al Makan Dictionary is expected to be three or four.

Khaled Abdel Rahim Al Sayed, supervisor of the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia project, said work is now underway to complete the first volume of the Dictionary of Places, which is an essential pillar in the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia to link places in Qatar with its authentic Arab history by rooting place names from linguistic dictionaries and others.

He linked it to poetic evidence, and documented information about each place through phonetic, morphological, semantic, lexical and encyclopedic analysis.

Al Sayed said the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia’s team consists of professors specialised in language, linguistics and literature at Qatar University, within the framework of scientific cooperation between the Katara Cultural Village Foundation and Qatar University.

Dr. Maryam Al Nuaimi, Director of the Qatar Cultural Encyclopedia Project Execution Committee, said the seven parts that were prepared from the daily life vocabulary include Arabic alphabets from 'Hamza' to 'Kha', and they are working to complete the rest of the letters.

The first volume of the dictionary has been allocated for this.

As for the dictionary of places, it consists of 7,506 entries that include all the words that make up the names of places in Qatar. Abu, Abba, Mother and includes 13 nicknames, she explained.

She said the Dictionary of Places works on surveying the environment of places in Qatar, specifying the linguistic dimension and the dialect’s relationship to Standard Arabic, after which, the encyclopedic geographical dimension, so the user of the encyclopedia can search for one place consisting of more than one word, such as “Umm Salal Muhammad,” wherein he can search for Umm Salal or Mohammed, in addition to the root search.

OACC Business Spotlight-Sierra Translation Services | - Sierra News Online - Translation

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

OACC Business Spotlight-Sierra Translation Services | Sierra News OnlineTranslation Service Market Projected to Hit USD 47.21 Billion at a 2.60% CAGR by 2030 - Report by Market Research Future (MRFR) - GlobeNewswire - Translation

New York, US, Sept. 27, 2022 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- According to a comprehensive research report by Market Research Future (MRFR), “Translation Service Market Research by Service Type, By Operation Type, By Component, Application - Forecast to 2030”, poised to create a valuation of USD 47.21 billion by 2030, pervasively growing at a 2.60% CAGR during the review period (2022-2030).

Translation Service Market Overview

These services come with a unique synergy of cutting-edge technology, highly experienced language experts, and multi-layered quality processes for all academic translation needs, making sure that research works get all the success they deserve. Service providers make sure that the translation work is treated so well that the quality and essence of the content are retained.

Translation services or language translation services allow people to push past those barriers of language, providing the assistance of a professional linguist with the ability to communicate on a global platform. With a variety of forms such as spoken interpretation, certified translation, localization, and globalization, translation services play a causal role in conveying messages accurately.

Players active in the translation service market are,

- Language Line Solutions (US)

- SDL (UK)

- Babylon Software LTD (Israel)

- Propio Language Services

- Vocalink

- Ingco International (US)

- CLS Communications (Switzerland)

Get Free Sample PDF Brochure:

https://ift.tt/eEJR79U

Industry Trends

Increased adoption of professional translation services in major end-user industries is a key growth driver. Besides, the growing demand from healthcare, travel & transport, media & entertainment, and the education industry boosts market size. Substantial investments in developing translation platforms and improving services drive market growth.

Businesses implement translation and interpretation services to focus on local content adaptations to succeed in a new culture. This process helps with all relatable content that appropriately fits into the local culture. Moreover, translation services help increase social media outreach and targeted email marketing campaigns and make e-commerce easier to navigate.

In marketing, translation services help to use many figurative languages, which need a high level of cultural understanding to translate. In the eCommerce sector, translation services are necessary to increase the market reach to customers who speak different languages. The rise in online marketing & SEO and the e-commerce sector substantiate the market valuation.

Conversely, complexities associated with the development of translation technologies and services are the major factors impeding market growth. Nevertheless, increasing implementations of AI-enabled service platforms in media & entertainment would support market growth during the review period. Also, the growing emphasis on business intelligence and competition across the industries and growing boost the development of the market.

Translation Service Market Report Scope:

| Report Metrics | Details |

| Market Size by 2030 | USD 47.21 billion |

| CAGR during 2022-2030 | 2.60% CAGR |

| Base Year | 2021 |

| Forecast | 2022-2030 |

| Report Coverage | Revenue Forecast, Competitive Landscape, Growth Factors, and Trends |

| Key Market Opportunities | Rising Marketing Needs and Privacy/Disclosure Laws |

| Key Market Drivers | Raw data and information are available all around us in bulk. |

Browse In-depth Market Research Report (110 Pages) on Global Translation Service Market:

https://ift.tt/urXWOV4

Translation Service Market Segments

The translation service market forecast is segmented into operation types, services, components, applications, and regions. The service segment comprises written translation, interpretation, and other services. The operation type segment comprises technical translation, machine translation, and others.

The component segment comprises hardware and software. The application segment comprises medical & healthcare, media & entertainment, IT & telecom, automotive, and others. The region segment comprises the Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific, and the rest of the world.

Translation Service Market Regional Analysis

North America leads the global translation service market, mainly due to technological advances. Besides, the large base of translation service providers in the region influences market shares. The rising adoption of advanced translation and interpretation services in various industry verticals in the region drives the growth of the regional market. Moreover, the rising penetration of natural language processing, machine learning, and multilingual translation technology substantiates the market growth in the region.

Europe is the second-largest market for translation services globally. The market growth attributes to the strong presence of notable players and large translation service deployments. Additionally, governments' high adoption of translation and interpretation services to decode messages floating through webs to control increased terror and crimes in the region pushes the development of the regional market. Substantial R&D investments by market players in developing multilingual translation technology increase the market size.

The translation service market is brisk in APAC due to the increasing cloud deployments of translation services. Furthermore, the massive uptake of language processing technology to enhance customer satisfaction and operational performance boosts regional market growth. Japan, China, Australia, and India are the major translation service markets in the region. Technology advancement and increased deployments of complex algorithms and statistical & analytical translation & interpretation services influence the market growth.

Ask for Discount:

https://ift.tt/rChL82M

Translation Service Market Competitive Landscape

The translation service market appears to be competitive due to the presence of several well-established players. Players initiate strategic approaches such as mergers & acquisitions, collaboration, innovation, and brand reinforcement to gain a larger competitive share. The market will witness intensifying competition in the future due to increased innovations, M&A, and R&D investments.

To support their strategic expansion into the global footprints and clients & interpreters, industry players acquire companies having highly compatible geographic footprints and a clear focus on interpreting services. Governments and ministries for customer service, digital government, and multiculturalism also introduce instant translation services.

For instance, on Sep. 05, 2022, the ministry of Customer Service and Digital Government introduced new instant translation services into the Australian Death Notification Service (ADNS) to allow people to access and navigate information in more than 50 languages. The ADNS is an online platform that allows customers to notify someone's death multiple organizations, reducing the lengthy 40-hour process to a 15-minute streamlined experience.

Talk to Expert:

https://ift.tt/SKxByQb

This new translation service will save the time consumed by overwhelmed paperwork and bureaucracy hassles that people face during the death of their near ones. The government thinks that it is important that their technologies are comprehensive and reflect modern Australia. A large number of customers have already been using the ADNS to send notifications to partner organizations, saving a vast amount of time.

Related Reports:

Global Language Translation Software Market, By Component, By Function, By Organization Size, By Vertical - Forecast 2027

Natural Language Processing Market research report: by Technology, by type, by Service, by deployment - Forecast till 2030

Intelligent Personal Assistant Market Information, by Deployment, By Technology - Forecast 2030

About Market Research Future:

Market Research Future (MRFR) is a global market research company that takes pride in its services, offering a complete and accurate analysis regarding diverse markets and consumers worldwide. Market Research Future has the distinguished objective of providing the optimal quality research and granular research to clients. Our market research studies by products, services, technologies, applications, end users, and market players for global, regional, and country level market segments, enable our clients to see more, know more, and do more, which help answer your most important questions.

Follow Us: LinkedIn | Twitter

Telescanner: a new entry in the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction - Boing Boing - Dictionary

There are many terms from classic and modern SF that remain unresearched, and the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction will be continually updated, especially as additional resources are put online. Boing Boing is syndicating new entries from the HDSF on a regular basis. (Read the series introduction.)

As science-fictional gadgets go, the scanner is a pretty familiar one: the need to get information on something, especially if its far away or hidden behind an obstacle, is rather important indeed. The earliest examples of the word scanner in science fiction date from the 1930s—about the same time as modern radar was being developed—but it can be hard to pinpoint which of these is an actual SF term. The various devices used to capture images of objects for television transmission were also called scanners, from the 1920s onwards, and the line between the real devices and the imaginary ones is not finely drawn.

One way to make something feel more techy is to simply slap a good prefix onto it (cyber- and e- were briefly popular in recent decades, before becoming stale), so it stands to reason that tele- would have been pressed into service. By the 1930s there were a variety of terms beginning that way: telepath as a verb; various teleport–related words; telescreen. Naturally, then, telescanner had to arise. The prefix serves multiple purposes here: it not only establishes that this really is operating at a distance, but it also sounds modern, or did at the time.

Although even then it may have been something of a cliché; by 1940 we have a tongue-in-cheek example of rewriting a western into a science-fiction story by replacing "lariat" with "tractor" and "binoculars" to "tele-scanners." Despite this, the word managed to stick around, and while the bare scanner is more common, the tele- version remains a regular alternative.

Mongolian edition of Dictionary of Chinese Cultural Knowledge published - Xinhua - Dictionary

ULAN BATOR, Sept. 27 (Xinhua) -- The inauguration ceremony of the Mongolian version of Dictionary of Chinese Cultural Knowledge was held on here Tuesday.

Around 20 Mongolian translators led by Menerel Chimedtseye, professor at the National University of Mongolia, and a leading Mongolian sinologist translated the dictionary over the past year.

"It is a 'classic' work that contains the basic knowledge of Chinese culture and covers many topics from ancient philosophy and concepts to modern science, technology, history, literature, art, customs, and lifestyle," Chimedtseye said at the ceremony.

"It can be said that such comprehensive and large-scale work, which introduces the culture of our country's longtime friendly and close neighbor, China, has never been published in the Mongolian language before," he said.

This is the first time that the dictionary has been published in a foreign language.

The launch ceremony of the book is part of a series of activities in the China-Mongolia Friendship Week that began here on Monday. ■

Monday, September 26, 2022

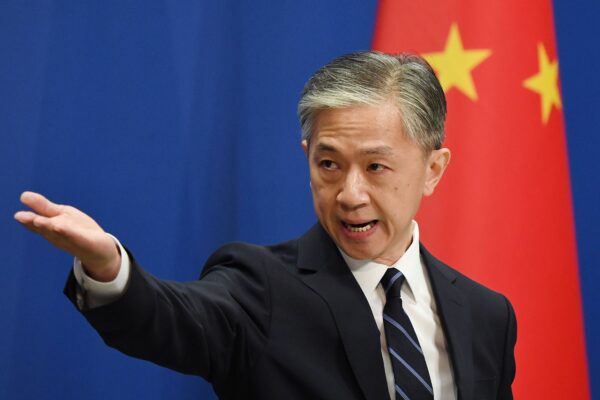

CCP's Official Diplomatic Statement Translation Can Be Misleading: Study - The Epoch Times - Translation

A new study shows that the official translation of communist China’s diplomatic statements may be sub-optimal and create misunderstandings, potentially leading to poor or even calamitous foreign policy responses.

According to Corey Lee Bell, a project and research officer at the University of Technology Sydney’s Australia-China Relations Institute, the People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) translations are of inconsistent quality, and may inadvertently—sometimes perhaps intentionally—convey different messages from the Chinese source.

Bell, in his research entitled ‘Translators and Traitors’: What to be wary of when reading translations of PRC diplomatic/foreign affairs statements, also argued that all translations from the MFA should ideally be substituted by professional translations where possible.

“One often cited source of English translations of the PRC’s MFA statements is the MFA’s official website. While it has become relatively comprehensive and prompt in its production of translations, its work is often described among professional translators in the PRC through the idiom ‘creating a cart behind closed doors’… i.e., a translation divorced from proper scrutiny or a translation that did not undergo a thorough quality review by a qualified first language speaker’,” Bell said.

English Translation Can be Stronger or Less Assertive than Chinese Source

Bell argues that there are often times when the MFA’s English translation is less strong in tone than the Chinese source, with a recent example being a response from the MFA spokesperson related to the United Nations Human Rights Office’s report—published on Aug. 31—on the Chinese regime’s treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region. He argues that this may reflect “the strategic use of discrepancies between a Chinese source and an official MFA English translation.”

On Aug. 11, right before the release of the report, an MFA spokesperson was asked by a China News Service representative for his opinion on a report compiled by the ‘China Society for Human Rights Studies.’ Wang’s reply included “three serious crimes” the United States has “committed” in the Middle East and surrounding areas.

“The first ‘crime/violation’, according to the MFA’s translation of the spokesperson’s remarks, was that ‘the U.S. has launched wars that damaged people’s right to life and survival.’ The original Chinese, however, was stronger in tone, stating that America had ‘wantonly launched’ (肆意发动 )these wars,” Bell said.

“The English translation also said that America ‘just cannot deflect responsibility for starting wars.’ This is a polite translation of the archaic/formal Chinese phrase (难辞其咎), which generally conveys the indefensibility of past actions, akin to the phrase ‘can hardly absolve oneself of blame/responsibility.’”

There are also cases in which English MFA translation is stronger in tone than the Chinese original, many involving the translation of Chinese idioms, which are often in the form of archaic four-letter word phrases, conveying “abstract ideas through depictions of events and concrete objects.”

The most recent example is the widely cited official translation of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Xi Jinping’s “Those who play with fire will perish by it” when attempting to warn U.S. President Joe Biden about Taiwan on a phone call in July, which was translated from a common Chinese idiom (玩火自焚).

“While ‘perish’ can be justified in the English translation, it is not necessary to capture the figurative sense of the idiom, which could simply be translated as ‘those who play with fire will get burned,’ Bell argued.

Another famous example is a translation of a phrase from Xi Jinping’s speech marking the centenary anniversary of the CCP in mid-2021, where he declared that the Chinese people would not allow any foreign forces to bully, oppress or enslave the country and any who dared would “have their heads bashed bloody against a Great Wall of steel forged by over 1.4 billion Chinese people.”

The phrase “heads bashed bloody” sparked controversy outside China and was featured in the headline of an article by The Washington Post.

Bell gave his own translation for reference: “Anyone that vainly attempts to do so will smash against the great steel wall forged by the flesh and blood of over 1.4 billion Chinese people49 and will fail dismally/have their noses bloodied (lit., ‘smash against the great steel wall… [so hard] that their heads will be cut open and bloodied’).”

MFA Translation Can Be Supplementary Source

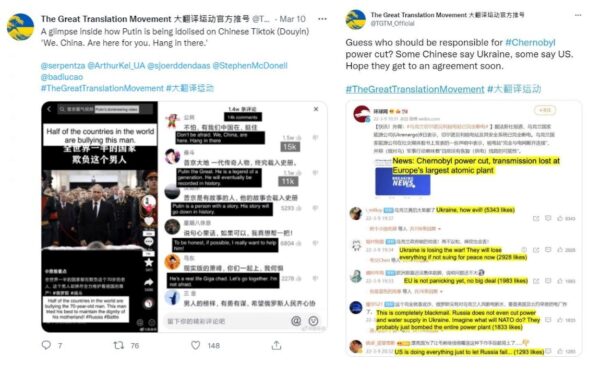

The author also noted the Great Translation Movement, which is an online translation campaign by anti-communist activists to expose the “hidden and less savoury elements of PRC political commentary.”

Despite the inadvertent or intentional discrepancies, Bell believes that MFA translations can sometimes be an important supplementary source to accurate translations of Chinese source texts.

“Since they are less directed at domestic image management, they may better reflect the tenor/substance of official diplomatic representations,” he said.

Follow

It's Good That Andor Doesn't Translate the Kenari For Us - Collider - Translation

Editor's Note: The following article contains spoilers for Episodes 1-3 of Andor.There are millions of cultures and peoples in the world of Star Wars, and we’ve gotten to know many of them over the past few decades of stories. Our newest addition to that extensive list came in the form of the Kenari in Andor. The Kenari are a group of people from a planet of the same name, and we learn that Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) was originally from this planet as well. But unlike so many of the cultures we’re introduced to in the Star Wars universe, the Kenari seem completely disconnected from the larger happenings of the galaxy and the Empire. When an Imperial ship plummets through their atmosphere the Kenari look at it with awe and fear before going to investigate what it is, unaware that they’re about to be unwittingly pulled into the fold of a cosmic war. Through flashbacks, we see Cassian (originally called “Kassa”) and his sister in their childhood as their village prepares to go investigate the wreckage, all the while characters talk to each other in Kenari which the show does not translate for us. We’re introduced to the Kenari as a total outsider, and thus we don’t get to know what their words actually mean. This choice to not translate for us may at first seem frustrating but in truth it helps to illuminate even more about the Kenari and their place in the galaxy.

This is far from the first time Star Wars has decided to not give captions for characters speaking another language. Chewbacca’s been speaking in incomprehensible trills since the very beginning and, similarly, R2-D2 has an expansive vocabulary we aren’t privy to. But the other characters respond in a language we as the audience can understand, the languages that are unfamiliar to us are commonplace in a galaxy far, far away. So even if the exact words are lost on us we can figure out the meaning through context. The Kenari are a departure from this. Not only are they humanoids who don’t speak what seems to be the universal language of all humans we’ve met so far, when they speak their language to others, they are not understood. We get no captions, only the context in which the words are spoken to base our understanding on.

The Kenari Are Outliers From Everything We've Seen So Far

The lack of translation does wonders in telegraphing the most important thing about the Kenari: they are wholly uninvolved in every conflict we have seen so far. These people have existed independently with their own culture and language and though we don’t know for how long, we know that freedom and safety are about to be destroyed as they’re pulled into the Empire’s line of fire. The Kenari are not like other peoples we have met in Star Wars, speaking other languages but still fully involved in the affairs of the galaxy at large, they have seemingly been living their own lives unaware of the massive wars being waged overhead.

It helps to show us as an audience how they are in over their heads because we know how violent the Empire can be, but they are only just finding out. Without translations, we can’t know the Kenari’s intentions just as they don’t know the intent of the officers that crashed on their planet until one of those officers starts shooting lasers at them. It’s a situation of mutual misunderstanding and providing the audience with the same language barrier as the characters

This isn’t to say that we can’t understand what the Kenari are saying at all. Even with no translations, actions, body language, and context are enough to show us what is happening even if we don’t understand the exact details. The lack of translation is not to paint the Kenari as lesser but as other, something completely outside the Star Wars we know and crushing any assumptions on the universality of the Empire and the language it largely uses. We don’t get to be privy to their language or details of their culture because it’s been decimated by the ill-timed arrival of some shipwrecked Imperial officers.

RELATED: ‘Andor’ Shows the Deterioration of the Star Wars Galaxy

The Kenari Are Dragging Into the Galactic Conflict

For so long it’s been easy to assume that everyone in Star Wars is on the same page. The reach of this civilization and its many species and cultures enough to make up the Republic and later the Empire has always been all encompassing for the stories we encounter. But the Kenari show us that our assumptions are false. There were still people living independently of Empire rule but, like with real world imperialism, as the Empire’s reach expanded so too did other peoples come into conflict with them only to be subsumed by them. The language of the Kenari is lost on us because they were not given the option of integrating into the larger galactic world but instead forced into it and made others by it. It's noteworthy that Cassian's original name, "Kassa", is the only word we get translated because Cassian is at this point in the narrative the last vestige of the Kenari. His name is all that is preserved through time. Other than the recognizable sound of his name, the rest is lost on us.

The language barrier also creates a sense of vulnerability. There’s some dramatic irony at play when the Kenari are introduced as we know more about what’s been happening in the larger galaxy scale than they do. So we watch the Kenari march off to investigate the fallen Imperial ship knowing it can only end in disaster. The language barrier can easily lead to misunderstandings and nearly eliminates the possibility of a peaceful resolution. Without translations we as the audience feel this vulnerability as we see Cassian confront Maarva (Fiona Shaw) on the crashed ship, completely unaware of what he’s stumbled into. We see clearly how out of his depth he is in this new situation and how difficult the coming challenges will be.

The Kenari didn’t have a choice in their involvement in the narrative, yet they are still actively transformed by it. We see that in Cassian shedding the language of his people to adopt the standard dialect of the galaxy and in Maarva’s sureness that Cassian would be killed if he remained on Kenari. Once you have been brought into the fold, even unwittingly, there is no turning back. And so that language is lost to us as an audience because the Kenari have been overrun by the Empire. The choice to not translate the Kenari for us only highlights their distance from the narrative as we know it and their unfortunate fate to be pulled into the orbit of something far beyond their control. We learn much more about the Kenari’s place in the galaxy through the lack of translations by allowing us as an audience to simulate their experience of first contact with a world beyond their imagination.

Complete New World Translation in Brazilian Sign Language Now Available - JW News - Translation

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Complete New World Translation in Brazilian Sign Language Now Available JW NewsSagamore Institute Study Attempts To Quantify Cost of Bible Translation - The Roys Report - Translation

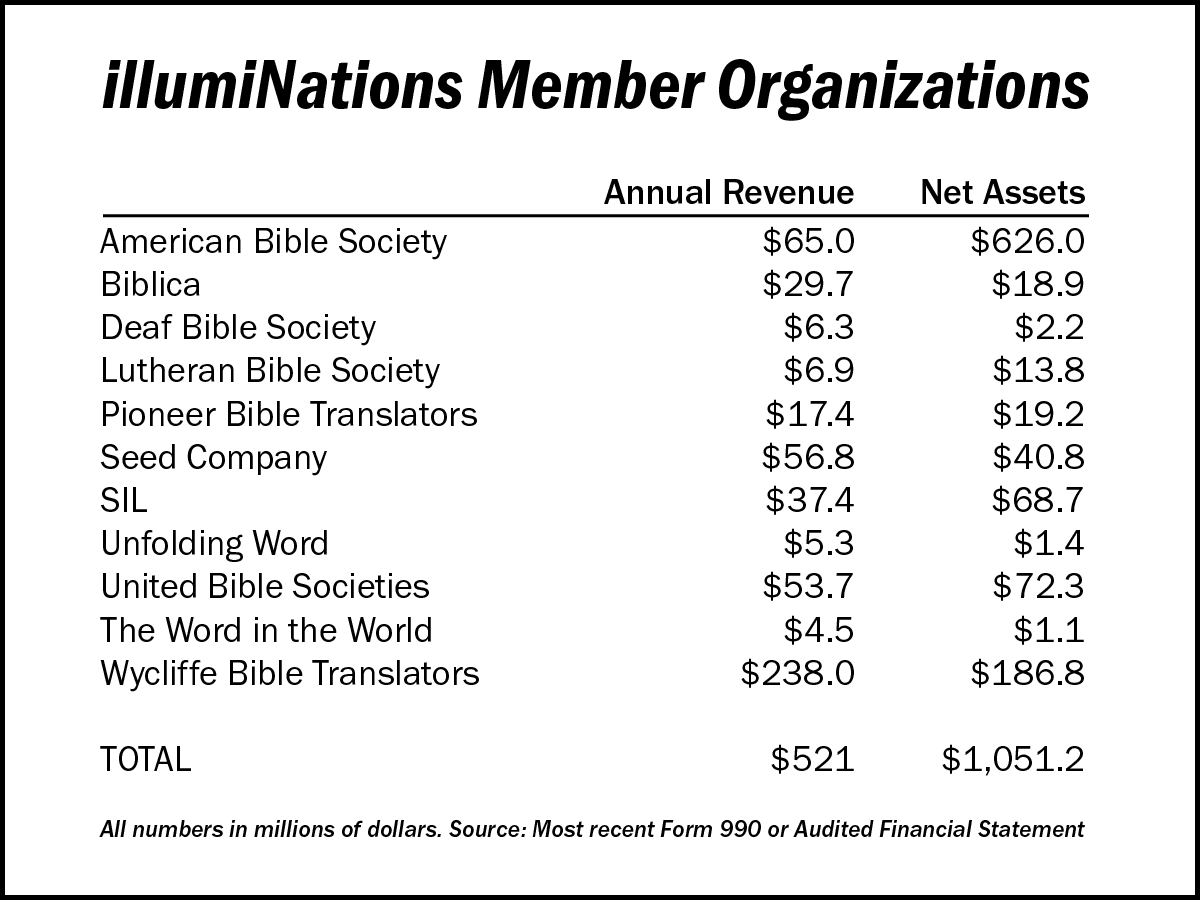

Bible translation organizations in the United States receive more than $500 million in donations per year. So how many Bibles actually get translated? And how much does a Bible translation cost?

Remarkably, the answer to that question is — nobody really knows.

That’s why the Sagamore Institute, an Indiana-based think tank, recently did a study to analyze the cost and use of funds in Bible translation. The study was funded by the Chattanooga-based Maclellan Foundation on behalf of the illumiNations Resource Partners. These are organizations and individuals who fund Bible translation efforts.

The findings include the following:

-

The average project cost of a “text translation” is $59,302 per year.

-

The average project cost of a complete written Bible is $937,446.

-

The “annual expenditure aggregate project cost” is $105 million.

-

On average, it takes 15.8 years to complete a Bible translation.

According to a statement, “the study distinguished between project costs (project development, accountability, translation tools, and translators) and support costs (local capacity, maintenance of translation tools, research and development, and alliance infrastructure) because support costs are typically underwritten by specific funding partners, rather than outside donors, and include recurring expenses.”

Give a gift of $25 or more to The Roys Report this month, and you will receive a copy of “Untwisting Scriptures: Wolves, Hypocrisy, Sin Leveling and Righteousness” by Rebecca Davis. to donate, click here.

The numbers released by the Sagamore Institute highlight the fact that the vast majority of dollars contributed to Bible translation organizations do not, in fact, go to Bible translation.

For example, the organizations that make up illumiNations took in more than $521 million last year (see chart), and these organizations produce less than 20 complete Bible translations in a year. If it really costs less than $1 million to produce the Bible, as the Sagamore Institute says, that means support and other costs could have topped $500 million.

The Sagamore study also highlights another reality of the Bible translation industry: the practice of money transfers (grants) between Bible translation partners. These transfers mean that simply adding up the revenue of various Bible translation organizations will likely result in double-counting of revenue. That’s one reason the Sagamore study says the amount of money spent on Bible translation is not in the neighborhood of $500 million per year but about $378 million in the 12-month period reviewed. The study excludes “SIL costs outside of those in partnership with Wycliffe USA; grants unrelated to American Bible Society in the United Bible Societies’ International Support Programme, and differences in the treatment of GAAP reconciliation items.”

However, even accepting the Sagamore Institute’s lower number of $378 million, that means more than two-thirds of the money donated annually to Bible translation organizations goes to activities other than Bible translation. The Sagamore study identifies $97 million in “translation support costs” and $109 million in “related Bible ministry costs.” Sagamore also identified $67 million in “activities conducted by translation partners that are unrelated to Bible translation or ministry.”

All of this means that the “fully loaded” cost of a Bible translation is certainly in the millions of dollars, and likely in the tens of millions.

Calvin Edwards has been studying the Bible translation industry for years. He also had questions about “support costs” and why they were not included in the calculations for the cost of a Bible translation.

“What are these?” he asked. “Do they relate directly to Bible translation? If support costs were included, what is the ‘full cost’ of a Bible translation?”

Edwards added, “The reported findings are interesting but not new, and much more information is required. Donors most want to know two things: how is the $500-plus million raised by Bible translators annually used, and how many Bibles are translated for the translation portion of the total? These are simple questions that have answers.”

According to Rob Panos of The Sagamore Institute, the study was based on information self-reported by the Bible translation organizations themselves. He said the numbers were “validated in aggregate through a review of audited financial statements.” He added, “It’s important to understand that this was not a rigorous audit of spending. It is a high-level view of the cost and use of funds in translation.”

This article was originally published at Ministry Watch.

Warren Cole Smith is president of MinistryWatch.com, a donor watchdog group. Prior to that, Smith was Vice President-Mission Advancement for the Colson Center for Christian Worldview.

Lions print dictionaries still have unsung benefits | Opinion - Southernminn.com - Dictionary

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Lions print dictionaries still have unsung benefits | Opinion Southernminn.comSunday, September 25, 2022

Was a dictionary really banned in Anchorage? Here's the real story of how the book was outlawed in schools - Anchorage Daily News - Dictionary

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/adn/EGTPS37FUFHCTNI75U527KUVEQ.jpg)

An advertisement by People For Better Education, Inc., that appeared in the July 7, 1976 edition of the Anchorage Times advocating for the dictionary ban. The ad was notably published after the dictionary had already been banned.

Part of a continuing weekly series on Alaska history by local historian David Reamer. Have a question about Anchorage or Alaska history or an idea for a future article? Go to the form at the bottom of this story.

Did you know that a dictionary was banned in Anchorage? Every September, every annual banned books week, it comes up again. Every year, the reading community — authors, librarians, teachers, publishers, booksellers, and consumers — come together to discuss ongoing censorship issues and the history of banned books. And the extraordinary decision to ban a dictionary, of all things, in Anchorage is often included in the dialogue. The details are often wrong, and the story is slightly more complicated than how it is usually presented, but the core of the narrative is true. A dictionary really was banned in Anchorage.

In the early 1970s, a group of concerned Anchorage parents led by Marroyce Hall formed a conservative school watchdog organization called the People for Better Education. Their first claim to fame came in 1974 when the group issued an unasked-for report on unruly behavior in local schools. The report cited rampant disciplinary problems, including thrown snowballs, “pop can hockey,” “general pushing and shoving,” and “displays of affection, such as passionate embraces on school grounds.” Given the existence of such unbelievably wicked behavior, the organization demanded schools add a roving security force.

In 1976, the group emerged with a new issue. They discovered a vulgar book present in many area elementary school libraries, the American Heritage Dictionary. The People for Better Education meticulously combed through every entry in the dictionary, a process one member described as “like digging (in) garbage.” When their labors were completed, they had identified 45 objectionable slang definitions.

Many of the offending words were included for their alternative meanings, including ass, ball, bed, knocker, nut, and tail. Per the dictionary, a “ball” can be “any of various rounded movable objects used in sports and games” or refer to “the testicles.” Similarly, “bed” might be a noun or a verb, a piece of furniture, or “to have sexual intercourse with.” The organization also disliked several idioms, including “shack up,” defined as “to live in sexual intimacy with another person, especially for a short duration.”

The Anchorage School Board, to their credit, took the complaint seriously. They empowered a committee of four parents and four staff members to review the text, which concluded that the dictionary should remain available to students. Undeterred, Hall, accompanied by Eileen Kramer, made a presentation to the school board on June 28, 1976, again demanding the removal of the dictionary.

To the surprise of board president Sue Linford, the board voted 4-3 to remove the dictionary. Millet Keller, Tom Kelly, Darlene Chapman, and Vince Casey voted in favor of the ban. Keller, who authored the motion to remove the dictionary, told the Anchorage Daily Times that such “vulgar, slang words” were “better left in the gutter.” Linford, Heather Flynn, and Carolyn Wohlforth voted against the ban. Said Linford, “I’m really at a loss to explain it ... This smacks of things I don’t think we want to encounter.”

The next day, the Anchorage Assembly voted unanimously to send a letter to the school board sharply rebuking their actions, warning that the dictionary ban would “stimulate further censorship pressures.” The letter further stated, “the overriding concern is preservation of individual and academic freedoms. We earnestly request that you reconsider your action without delay.” Several Assembly members also went on the record with more personal comments. Chairman Dave Rose described the ban as “absolutely ludicrous.” Lidia Selkregg declared, “I’m shocked at the board’s action. A dictionary is a most sacred document.” Fred Chiei said, “Now I suppose they’d like to go for the Bible. Lots of good words with dirty meanings there.”

Most of the public comments on the ban criticized the action. School board candidate Pam Siegfried said, “I do not want to have my kid go to a library which has been picked clean by concerned parents. Once somebody starts censoring, where does it stop?” The Anchorage Daily News editorialized, “We can’t imagine any action by a board of education which could go against the American grain more than censoring research tools.” As one resident wrote in a letter to the Daily News, “You don’t stop the use of ‘vulgar’ language by removing one book which contains the definition of four or five slang words but rather by parental guidance and by making it clear to your children that such language is not acceptable to you.”

Around the same time, several members of Anchorage’s Mexican American community, including the Chicano Interservice Association, complained that three books on Mexico in local elementary libraries presented stereotyped images of Mexico. The school board ordered the removal of these books at the same meeting when they banned the American Heritage Dictionary. One of these books, “All Sorts of Things” by Theodore Clymer, includes a story of a Mexican town where everyone is lazy, unintelligent, wears tattered sombreros, and eats tortillas exclusively. A month later, the school board rescinded their ban on two of these books on Mexico, though not on “All Sorts of Things.”

The American Heritage Dictionary remained forbidden. As might have been reasonably expected, the ban increased interest in the book and the supposedly objectionable words, underpinning the ludicrous nature of such censorship. The downtown Book Cache (remember when there were multiple Book Caches in town?) prominently displayed a rack full of copies. A spokesperson noted the store “has gotten more requests and comments” since the ban. She added, “I think people are just curious.”

As Katherine Chamberlain of the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom stated in 2010, “Condemning the American Heritage Dictionary for its ‘objectionable language’ in effect condemns the English language itself.” The language existed, whether one considered it vulgar or not. Moreover, children then certainly already knew far more profane words than tame terms like “balls” or “tail.”

In addition, Anchorage of the 1970s was a more openly risqué city than it is today. Prostitutes walked the streets, and there were far more strip clubs, XXX theaters, and adult bookstores. The abundant massage parlors and escort services openly marketed their illicit services, establishments like the Touch N Glow, Foxy Lady, and Sensuous Lady. The People for Better Education might as well have expanded their efforts to include banning the phone book since it included sections for such businesses. The newspapers ran advertisements for XXX features, resulting in movie listing pages that included both Linda Lovelace’s “Deep Throat II” and Disney’s “Bambi.”

The People for Better Education were less successful with their future demands, which included the requested removals of several other books and films. In 1977, they notably challenged the showing of the film “The Lottery” in classes. The film is based on the classic short story by Shirley Jackson, wherein town’s people ritually kill a fellow resident every year solely because it is tradition.

The organization was perhaps more successful as an inspiration for similar censorship movements elsewhere. Amid a general rise in school district book bans across the country, the American Heritage Dictionary was subsequently banned in Cedar Lake, Indiana, Eldon, Missouri, Folsom, California, and Churchill County, Nevada in 1976, 1977, 1982, and 1992, respectively.

Having protected children from selected dictionaries, the Anchorage school board next targeted LGBT teachers. Beginning in the summer of 1977, the board tried to suspend and then fire Government Hill Elementary teacher Michele Lish for the perceived sin of being a lesbian. While Lish had a stellar reputation as an educator, the board might have found a way to dismiss her quickly if they had been willing to endure the due process for such a removal. However, the board had no interest in any public accounting and refused to grant Lish a hearing. By September, the courts had twice blocked the suspension and dismissal given the lack of said hearing. Still, the school board dragged the conflict out until January 1978, when Lish accepted a non-teaching position in the district. Coincidentally, that same month, the Copper River School District board passed a resolution banning LGBT employees.

While the dictionary ban does not seem to have ever been officially lifted, the removal was eventually forgotten or ignored. Today, the Anchorage School District library catalog lists several American Heritage Dictionary editions available throughout the district.

The way history works is that the same scenarios tend to repeat, different in the specifics but consistent at their core. Schools should be open, welcoming institutions. Instead, far too many people far too often expend their energies trying to restrict access to literature, knowledge, and access.

Key sources:

Babb, Jim. “Assembly Raps Dictionary Ban.” Anchorage Daily News, July 1, 1976, 1.

“Board Ousts ‘Vulgar Dictionary.’” Anchorage Times, June 29, 1976, 1, 2.

“Books on Mexico Restored.” Anchorage Daily News, August 11, 1976, 2.

Chamberlain, Katherine. “Spotlight on Censorship—The American Heritage Dictionary.” Intellectual Freedom Blog, Office of Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association, September 28, 2010.

Doherty, Nancy. “Dictionary Falls Over Dirty Words.” Anchorage Daily News, June 30, 1976, 1, 2.

Hunter, Don. “Dictionary Ban Draws Criticism of Assembly.” Anchorage Times, July 2, 1976, 1, 2.

“National News.” Lesbian Tide, March/April 1978, 18.

“Our Views: For Shame.” Anchorage Daily News, July 2, 1976, 4.

“Siegfried Supports Practical Education.” Anchorage Times, October 2, 1976, 6.

“The Scene.” Anchorage Daily News, July 17, 1976, 10.

“Teacher Kept Out of Classroom.” Anchorage Daily News, January 6, 1978, 1.

Tousignant, Adele. Letter to the editor. “What’s Vulgar?” Anchorage Daily News, July 8, 1976, 4.

Warren, Elaine. “Group Calls for School Reforms.” Anchorage Daily News, August 14, 1974, 2.

1464 books, 74 years and counting: How the world's largest Encyclopaedic Sanskrit Dictionary is shaping up - The Indian Express - Dictionary

After several years, the doors of the scriptorium and the editorial room of the prestigious Encyclopaedic Sanskrit Dictionary at Pune’s Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute in Pune were opened for students and the general public. The year of completion of this gigantic dictionary project, which commenced in 1948, remains unknown. But the final word count is estimated to touch 20 lakh and would be the world’s largest dictionary of Sanskrit.

The Project

Linguist and Sanskrit Professor SM Katre, founder of India’s oldest Department of Modern Linguistics in Deccan College, conceived this unique project in 1948 and served as the dictionary’s first General Editor. It was later developed by Prof. AM Ghatage. The project is a classic example of painstaking, patient and relentless efforts of the Sanskrit exponents for the last seven decades.

The current torchbearers of the Encyclopaedic Sanskrit Dictionary project is a team of about 22 faculty and researchers of Sanskrit, who are now working towards publishing the 36th volume of the dictionary, consisting of the first alphabet ‘ अ ‘ .

Subscriber Only Stories

Between 1948 – 1973, around 40 scholars read through 1,464 books spread across 62 knowledge disciplines – starting from the Rigveda (approximately 1400 B.C.) to Hāsyārṇava(1850 A.D.) – in search of words that could be added to this unique dictionary.

They covered subjects like the Vedas, Darśana, Sahitya, Dharmaśāstra, Vedānga, Vyakarana, Tantra, Epics, Mathematics, Architecture, Alchemy, Medicine, Veterinary Science, Agriculture, Music, Inscriptions, In-door games, warfare, polity, anthology along with subject-specific dictionaries and lexicons.

In the non-digital era, these scholars noted details of every new word onto small paper reference slips. They mentioned details like the book title, context in which the word was used, its grammatical category (noun/verb etc.), citation, commentary, reference, exact abbreviation, and date of the text. It was signed off by the creator of the slip and its verifier.

It took 25 years for these scholars to complete the word extraction process from around 1,464 books to generate one crore reference slips. All these paper slips have been well preserved, alphabetically, in one of the rarest scriptorium – the soul of the dictionary – inside over 3,057 specially-designed metal drawers. They have also been scanned and preserved digitally.

Word-by-word

Advertisement

While this dictionary contains words in alphabetical order, it follows historic principles in stating the meaning. In addition to the word meaning, the dictionary also provides additional information, references, and context of the respective word used in a particular literature. That is why, it is an encyclopaedic dictionary wherein words have been arranged according to the chronological order of their references appearing in the text.

For example, the word beginning with the letter ‘ अ ‘, like agni, will have all the citations from Sanskrit texts starting with Ṛgveda and the references from the texts following Ṛgveda, chronologically arranged. This helps a reader to understand the historical development of the meaning of the word.

“Sometimes, a word can have anywhere between 20 to 25 meanings as it varies depending on the context of use and books. Once the maximum possible meanings are found, the first draft, called an article, is published. This is then proof-read and sent to the General Editor for his first review. Upon finalising, the article of one word is readied and sent to the press. It is once again proof-read by the scholars and the General Editor, before it is finalised as a dictionary entry.” said Sarika Mishra, an Editorial Assistant on the Project.

Publications

Advertisement

While the first volume took three years to be published in 1976, technological intervention and an exclusive software with a font named KoshaSHRI have quickened the process.

“Now, we are able to publish a volume in little over a year. Approximately 4,000 words are incorporated in a volume,” said Onkar Joshi, also an Editorial Assistant of the Project.

In case of any missing information observed in the reference slips, the scholars re-read/scan the 1,464 books, now digitised, effectively making it a double reading of voluminous Mahabharata (18 Parvans), Vedas and alike.

” We can now use the software to easily scan through the books. In the past, this used to be done manually and would be time consuming,” Onkar added.

Since 1976, a total of 6,056 pages of words starting with the first alphabet ‘ अ ‘ have been published in 35 volumes.

Advertisement

” Alphabet ‘ अ ‘ has the maximum words and we have published 35 volumes consisting of words starting from this alphabet. Work on the 36th volume is underway,” said Sanhita Joshi, also an Editorial Assistant of the Project.

Unique and the largest dictionary

Pro Vice-Chancellor Professor Prasad Joshi is the ninth General Editor, and third from the family after his father and uncle, to work in this project.

Advertisement

“This job is a minute-to-minute and day-to-day job,” said Prof Joshi, who has been in-charge of the project since 2017.

Asked if there is any other language in the world that has such a rich and vast vocabulary, he said, “Possibly, the English language dictionary based on historical principles, which took nearly 100 years to be completed, will come close. But the Sanskrit dictionary has wider scope.”

Advertisement

For comparison, the Oxford English dictionary, with 20 volumes and 2,91,500 word entries so far, remains among the most popularly used dictionaries. The Woordenboek Der Nederlandsche Taal (WNT) is another large monolingual dictionary in Dutch. It contains 4.5 lakh words in 17 volumes.

The Encyclopaedic Sanskrit Dictionary, once ready, will be three times larger. The 35 volumes published so far contain about 1.25 lakh vocables (word).

Though there are 46 alphabets in Sanskrit language and several more decades of work lay ahead towards completion of this project, it is estimated that in the end, it will be a dictionary with a total vocabulary of 20 lakh words.

Future

Prof Joshi’s team is the crucial link between the past and the future, and has a big responsibility to keep Sanskrit alive. But there is a real shortfall of Sanskrit linguists.

“Overall, language studies have remained on the backfoot. We need readers for the vast volumes of scriptures and literary works lying unread,” he said.

But young scholars such as Bhav Sharma, Editorial Assistant and Project’s Secretary, are now reaching out to the public aimed to inspire a few.

“We need to showcase to the students the efforts and processes required for dictionary-making. We are planning student-centric activities in the near future so that there is hands-on learning,” said Sharma.

Presently, all the published volumes remain accessible in hard copy format.

The college administration is working aggressively towards making digital copies available within a year.

The Project, KoshaSHRI, under which the website for online access of the Dictionary will be made, also consists of a customised software which is presently under testing and development.

This will speed up the process of Dictionary making in the coming years.

Thursday, September 22, 2022

OpenAI Releases Open-Source 'Whisper' Transcription and Translation AI - Voicebot.ai - Translation

Whisper Writing

Whisper trained its ASR model on 680,000 hours of “multilingual and multitask” data pulled from the web. The idea is that a broad approach to data collection improves Whisper’s ability to understand more speech because of the different accents, environmental noise, and subjects discussed. The AI can understand and transcribe many languages and translate any of them into English. You can see an example in the Korean song translated and transcribed below.

The @OpenAI Whisper speech to text model is multilingual and can even transcribe K-Pop:https://t.co/x8TtZmPR1m pic.twitter.com/PNY3Gs2kjP

— Andrew Mayne (@AndrewMayne) September 21, 2022

While impressive, OpenAI’s research paper suggests the ASR is really only that successful in about 10 languages, a limitation likely stemming from how two-thirds of the training data is in English. And while OpenAI admits Whisper’s accuracy doesn’t always measure up to other models, the “robust” nature of its training puts it ahead in other And though the “robust” training enables Whisper to discern and transcribe speech through background noise and accent variations, it also creates new problems.

“Our studies show that, over many existing ASR systems, the models exhibit improved robustness to accents, background noise, technical language, as well as zero shot translation from multiple languages into English; and that accuracy on speech recognition and translation is near the state-of-the-art level,” OpenAI’s researchers explained on GitHub. “However, because the models are trained in a weakly supervised manner using large-scale noisy data, the predictions may include texts that are not actually spoken in the audio input (i.e. hallucination). We hypothesize that this happens because, given their general knowledge of language, the models combine trying to predict the next word in audio with trying to transcribe the audio itself.”

OpenAI is often in the news for GPT-3 and related products like text-to-image generator DALL-E. Whisper offers a glimpse at how the company’s AI research extends into other arenas. Whisper is open-source, but the value of neural net AI speech recognition for consumer and business purposes is conclusively proven at this point. Whisper could be a starting point for OpenAI to join in, as the researchers already speculated.

“We anticipate that Whisper models’ transcription capabilities may be used for improving accessibility tools. While Whisper models cannot be used for real-time transcription out of the box – their speed and size suggest that others may be able to build applications on top of them that allow for near-real-time speech recognition and translation. The real value of beneficial applications built on top of Whisper models suggests that the disparate performance of these models may have real economic implications.

OpenAI Drops GPT-3 API Prices As Enterprise Adoption Rises

OpenAI Starts Letting DALL-E 2 Users Edit Faces on Synthetic Images

GitHub’s Copilot AI Coding Assistant Boosts Developer Productivity and Happiness: Report

Wednesday, September 21, 2022

Too much trust in machine translation could have deadly consequences. - Slate - Translation

Imagine you are in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language and your small child unexpectedly starts to have a fever seizure. You take them to the hospital, and the doctors use an online translator to let you know that your kid is going to be OK. But “your child is having a seizure” accidentally comes up in your mother tongue is “your child is dead.”

This specific example is a very real possibility, according to a 2014 study published in the British Medical Journal about the limited usefulness of AI-powered machine translation in communications between patients and doctors. (Because it’s a British publication, the actual hypothetical quote was “your child is fitting.” Sometimes we need American-British translation, too.)

Machine translation tools like Google Translate can be super handy, and Big Tech often promotes them as accurate and accessible tools that’ll break down many intra-linguistic barriers in the modern world. But the truth is that things can go awfully wrong. Misplaced trust in these MT tools’ ability is already leading to their misuse by authorities in high-stake situations, according to experts—ordering a coffee in a foreign country or translating lyrics can only do so much harm, but think about emergency situations involving firefighters, police, border patrol, or immigration. And without proper regulation and clear guidelines, it could get worse.

Machine translation systems such as Google Translate, Microsoft Translator, and those embedded in platforms like Skype and Twitter are some of the most challenging tasks in data processing. Training a big model can produce as much CO2 as a trans-Atlantic flight. For the training, an algorithm or a combination of algorithms is fed a specific dataset of translations. The algorithms save words and their relative positions as probabilities that they may occur together, creating a statistical estimate as to what other translations of similar sentences might be. The algorithmic system, therefore, doesn’t interpret the meaning, context, and intention of words, like a human translator would. It takes an educated guess—one that isn’t necessarily accurate.

In South Korea, a young man used a Chinese-to-Korean translation app to tell his female co-worker’s Korean husband they should all hang out together again soon. A mistranslation resulted in him erroneously referring to the woman as a nightlife establishment worker, resulting in a violent fistfight between the two in which the husband was killed, the Korea Herald reported in May. In Israel, a young man captioned a photo of himself leaning on a bulldozer with the Arabic caption “يصبحهم,” or “good morning,” but the social media’s AI translation rendered it as “hurt them” in English or “attack them” in Hebrew. This led the man, a construction worker, to being arrested and questioned by police, according to the Guardian in October 2017. Something similar happened in Denmark, where, the Copenhagen Post Online reported in September 2012, police erroneously confronted a Kurdish man for financing terrorism because of a mistranslated text message. In 2017, a cop in Kansas used Google Translate to ask a Spanish-speaker if they could search their car for drugs. But the translation was inaccurate and the driver did not fully understand what he had agreed to given the lack of accuracy in the translation. The case was thrown out of court, according to state legal documents.

These examples are no surprise. Accuracy of translation can vary widely within a single language—according to language complexity factors such as syntax, sentence length, or the technical domain—as well as between languages and language pairs, depending on how well the models have been developed and trained. A 2019 study showed that, in medical settings, hospital discharge instructions translated with Google Translate into Spanish and Chinese are getting better over the years, with between 81 percent and 92 percent overall accuracy. But the study also found that up to 8 percent of mistranslations actually have potential for significant harm. A pragmatic assessment of Google Translate for emergency department instructions from 2021 showed that the overall meaning was retained for 82.5 percent of 400 translations using Spanish, Armenian, Chinese, Tagalog, Korean, and Farsi. But while translations in Spanish and Tagalog are accurate more than 90 percent of the time, there’s a 45 percent chance that they’ll be wrong when it comes to languages like Armenian. Not all errors in machine translation are of the same severity, but quality evaluations always find some critical accuracy errors, according to this June paper.

The good news is that Big Tech companies are fully aware of this, and their algorithms are constantly improving. Year after year, their BLEU scores—which measure how similar machine-translated text is to a bunch of high quality human translations—get consistently better. Just recently, Microsoft replaced some of its translation systems with a more efficient class of AI model. Software programs are also updated to include more languages, even those often described as “low-resource languages” because they are less common or harder to work with; that includes most non-European languages, even widely used ones like Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic, to small community languages, like Sardinian and Pitkern. For example, Google has been building a practical machine translation system for more than 1,000 languages. Meta has just released the No Language Left Behind project, which attempts to deploy high-quality translations directly between 200 languages, including languages like Asturian, Luganda, and Urdu, accompanied by data about how improved the translations were overall.

However, the errors that lead to consequential mistakes—like the construction worker experienced—tend to be random, subjective, and different for each platform and each language. So cataloging them is only superfluously helpful in figuring out how to improve MT, says Félix Do Carmo, a senior lecturer at the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Surrey. What we need to talk about instead, he says, is “How are these tools integrated into society?” Most critically, we have to be realistic about what MT can and cannot do for people right now. This involves understanding the role machine translation can have in everyday life, when and where it can be used, and how it is perceived by the people using it. “We have seen discussions about errors in every generation of machine translation. There is always this expectation that it will get better,” says Do Carmo. “We have to find human-scale solutions for human problems.”

And that means understanding the role human translators still need to play. Even as medications have gotten massively better over the decades, there still is a need for a doctor to prescribe them. Similarly, in many translation use cases, there is no need to totally cut out the human mediator, says Sabine Braun, director of the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Surrey. One way to take advantage of increasingly sophisticated technology while guarding against errors is something called machine translation followed by post-editing, or MT+PE, in which a human reviews and refines the translation.

One of the oldest examples of a company using MT+PE successfully is detailed in this 2012 study about Autodesk, a software company that provides imaging services for architects and engineers, which used post-editing for machine translation to translate the user interface into 12 languages. Other similar solutions have been reported by a branch of the consulting company EY, for example, and the Swiss bank MigrosBank, which found that post-editing boosted translation productivity by up to 60 percent, according to Slator. Already, some machine translation companies have stopped selling their technologies for direct use of clients and now always require some sort of post-editing translation, Do Carmo says. For example, Unbabel and Kantan are platform plugins that businesses add into their customer support and marketing workflows to reach clients all over the world. When they detect poor quality in the translated texts, the texts are automatically routed to professional editors. Although these systems aren’t perfect, learning from these could be a start.

Ultimately, Braun and Do Carmo think that it’s necessary to develop holistic frameworks that go far beyond the metrics used at the moment to assess or evaluate quality of translation, like BLEU. They would like to see the field working on an evaluation system which encompasses the “why” behind the use of translation, too. One approach might be an independent, international regulatory body to oversee the use and development of MT into the real world—with plenty of social scientists on board. Already, there are many standards in the translation industry as well as technological standardization bodies, like the W3 organization—so experts believe it can be done, as long as there is some more organization in the industry.

Governments and private companies alike also need clear policies about exactly when officials should and should not use machine translation tools, either free consumer ones or others. Neil Coulson is the founder of CommSOFT, a communication and language software technology company trying to make machine translation safer. “Police forces, border-control agencies, and many other official organizations aren’t being told that machine translation isn’t real translation and so they give these consumer gadgets a go,” he says. In March 2020, his organization sent out a Freedom of Information request to 68 different large U.K. public-sector organizations asking for their policies on the use of consumer gadget translation technologies. The result: None of these organizations had any policy for their use of MT, and they do not monitor any of their organizational or staff’s ad-hoc use of MT. This can lead to an unregulated, free-for-all landscape in which anyone can publish a translation app and claim that it works, says Coulson. “It’s a ‘let a thousand flowers bloom’ approach … but eventually someone eats a flower that turns out to be poisonous and dies,” says Coulson.